It has been a while since a gig of this scale has been arranged, I’m told. The organisers are new, the set list fresh but the players are all old hands. The musicians involved may be on the verge of crossing their prime if they already haven’t but they feel a sense of excitement and urgency all the same. After a long hiatus, Aamir Zaki will be performing in front of a massive audience and the players are all amped up to make it a gig to remember.

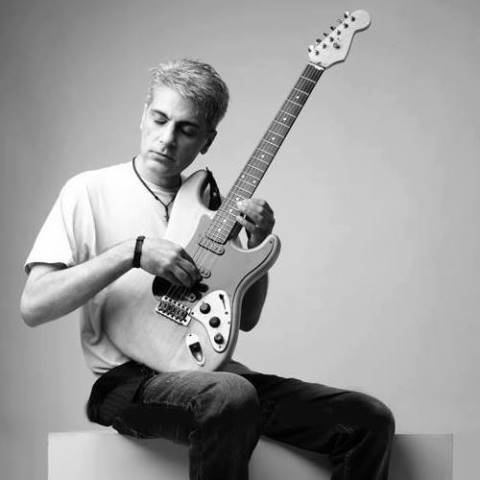

PHOTO: HASAN ANSARI/EXPRESS

PHOTO: HASAN ANSARI/EXPRESSAs Zaki walks in, reading glasses propped on his nose, a guitar case in hand, he receives a professor’s welcome even though he looks like someone who would incite you to rise against the education system while leading the charge against it. He still has his long dark hair. A signature button-down shirt still rests on his slender frame.

It is the first time I’m meeting Pakistan’s own guitar god. I’m confused and intimidated as is, but it get’s worse when Zaki notices me as the odd one out. As I stare at the roof like a clueless fanboy, I hear him say: “Koi rehta hai aasmaan mae kya? (Does anyone live in the sky?)”

I had assumed Zaki would be another Western music-inspired rock star so I’m quite shocked to hear him utter a Jaun Elia verse. “Jaun, he is great,” I respond, as the whole room goes silent. “Good that you know Jaun, let’s talk after the jam,” he winks. I wait for him outside.

That evening, we talked more about Jaun than about Zaki’s gig. He told me he tried and failed, time and again, to compose the same ghazal. But that was the beauty of it, according to him.

As I listened to Zaki go on about Jaun, I noticed an uncanny resemblance between the two on account of their sharp facial features and messy hair. I could not help but point it out to him. “I heard he was also a bit crazy like me,” he replied, laughing endlessly. Perhaps it was the other way round.

Two years after Zaki’s death, I find a lot more in common between the poet and the maestro. Not only were both notoriously reclusive and anti-social with a terrible personal life beset by addiction, they also managed to put out just one compilation of their work in their lifetime. Shayad is Jaun’s only work published while he was alive and Signature is the only album Zaki managed to release as a solo effort.

We are fortunate that Jaun’s legacy did not end with his life and only grew posthumously. A circle of friends and dedicated enthusiasts ensured this by compiling and publishing his works, enhancing the poet’s body of work.

Zaki did not have many friends or an influential circle of fans. The few well-wishers he had eventually got tired of his mood swings. The late Omer Sheikh of EMI once recalled that Zaki was offered a ‘Hollywood project’ that he oversaw as his manager, right after the release of Signature. But Zaki went MIA the morning a meeting to hash out financial details was set to take place. Zaki finally emerged when Sheikh rushed to the guitarist’s Tariq Road house and banged at his door. Only Zaki was no longer interested in the project because his kittens had been throwing up.

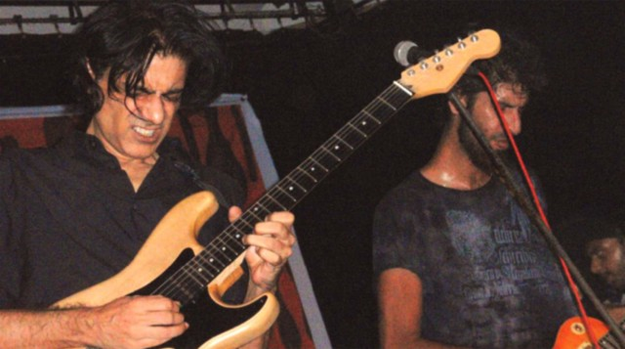

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITYIt was always difficult to get a grip on Zaki or convince him to get a grip on his life and career it seems. Music and musicians was the only consistent thing about them. Zaki could be jamming for Coke Studio at one point in the day only to go meet some no-name producer in 13D-1 Gulshan-e-Iqbal later because he loved his vision. They would connect on some random thought and as night turned into day, a jamming session would turn into a recording. Zaki would then ride off, like a triumphant hero, in the rising sun.

Anecdotes like these make it difficult to trace who with or where Zaki’s unreleased music lies. It is as confusing as trying to ascertain whether one of Jaun’s verses can be attributed to the four compilations of his poetry or if it was just a fragment he randomly scribbled on cigarette foil for a friend or stranger who offered him a fag.

The story of Zaki’s lost music starts in Karachi and ends in London. It bounces around different studios like an orphaned child waiting to be fostered. Friends, collaborators and students star as eyewitnesses in a search that involves fond memories, a mythical hard drive and a woman who won’t let Zaki die.

The music behind the man

Music producer Faisal Rafi was a teenager when he first met Zaki. In the years since, the two have worked together and played music together. For Rafi, Zaki is the most prolific musician whose work stands out for both thought and execution.

“Zaki was the most unplanned musician and that was part of his genius,” says Rafi. “You could call him to play anything, literally any style and he’ll give you something incredible in 15 minutes. The sad part is that the music he had been working on since the 90s is completely lost.”

PHOTO: EXPRESS

PHOTO: EXPRESSAccording to Rafi, Zaki had worked on a concept album and hundreds of other songs that never saw the light of day. One of the albums that Rafi had the pleasure of listening to was based around foley sounds and dialogues – random people would chitchat behind a layer of instrumental music giving the impression of noise.

“It was some crazy work,” remembers Rafi. “But way ahead of its time for the 90s. He went to meet a number of record labels but the likes of Sadaf records really had no inclination towards something so avant garde. So it got buried."

Rafi also recorded Zaki for Kaavish’s album Gunkali and some of Arieb Azhar’s songs. What he found most fascinating was Zaki’s attitude towards his own songs. “Zaki would record a certain melody line for a song and then disappear, for months and sometimes years,” laughs Rafi. He says he would sometimes end up calling Zaki to request that he complete the song he left halfway.

“So, a part of his genius was this randomness. And then, his taste in music changed so radically and suddenly that you couldn’t believe. How he switched from listening to Ozzy Osborne to John Coltrane and from straight on progressive rock to Western classical and then Mehdi Hassan was inspiring.”

Rafi also recorded some of Aamir Zaki’s solo tracks such as Street Signs that featured Zoe Viccaji and Maaz Maudood on vocals. Right now, he is in the process of setting up a new audio facility and that has given him an opportunity to overhaul the archives and look for Zaki’s recordings. He has not been very successful so far but remains positive that something will surface which he will finish and release after taking consent from Zaki’s family.

The vision beyond his time

Zaki taught guitars at the National Academy of Performing Arts (Napa) when Ahsan Bari of Sounds of Kolachi fame pursued a diploma in music from the institute that he would complete in 2009. Bari would eventually become Zaki’s disciple, collaborator and keeper of secrets but the beginning of this relationship was not pleasant at all.

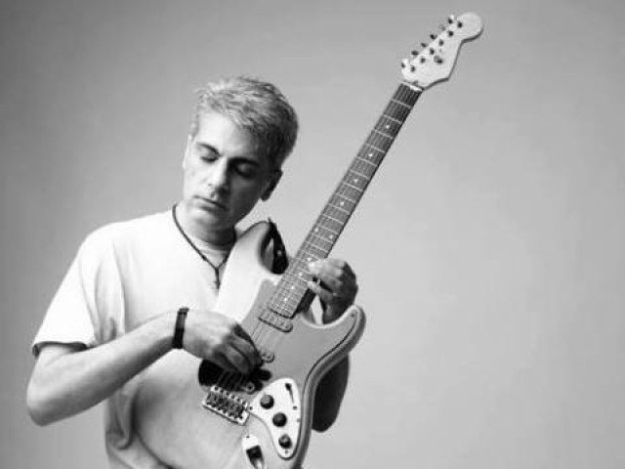

PHOTO: PUBLICITY

PHOTO: PUBLICITY“To be honest with you, Zaki wasn’t the best of teachers,” Bari tells The Express Tribune. “Since Zaki himself was way ahead of the time, he wouldn’t realise that his students may not be so forward-thinking. Even then, those who were curious enough would eventually leech onto him and extract whatever his mad genius could offer.”

Bari was one of them. They worked together for the first time in the same 2010 gig I mentioned in the beginning. The two did not lose touch in the five years or so that followed.

One summer day Bari got a random call from Zaki asking him to come over immediately. He rushed to the master’s place to witness a rare sight. “Mehdi Hassan Khan ghazals were playing in the background and Zaki was catching up with a beautiful chord progression on the guitar. ‘Yaar yeh karna hai (This is what he have to do),’ he told me. He wanted to reinterpret Khan sb’s music,” recalls Bari.

Zaki felt no one heard Khan sb the way he did and had a strong urge to share his take on the ghazal maestro, a dream that would never culminate.

Another mega project was to merge jazz improvisations with Hindustani classical ragas in the Western classical domain to create something more than merely fusion of genres. In fact he was also quite adamant on recording a complete catalogue of ragas on guitar and make it available for public consumption.

“You have to understand that Zaki took a lot of pride in being Pakistani. There’s a reason why he was so obsessed with the raga system. He considered Hindustani classical his own music and regardless of how fine a Western, blues or jazz musician he was, he wanted to know more about and innovate his own music,” says Bari.

He feels Zaki was the only mainstream musician in Pakistan who was theoretically and practically sound in the art of orchestration. He could be listening to a classical bandish and imagining it being performed by a symphony orchestra inside his head. As a result of which his ideas were holistic and do-able. Perhaps the Mehdi Hassan dream project isn’t a far cry.

The Sounds of Kolachi frontman plans to kick off the Zaki dream project in the next quarter of this year. Bari is planning to compose some pieces based on Zaki’s study and theoretical framework and have the finest musicians such as Omran Shafique and Faraz Anwar contribute.

“I exactly know what he wanted to do with Khan sb’s work. We spoke at length about the concept and execution. It’ll be something more new age and nuanced than Hariharan’s Kaash Aisa Hee Koi project. It’s quite unique,” explains Bari.

The spellbinding jam sessions

The search for Zaki’s lost miracles took us back to Emu’s Studio. Zaki was often seen hanging around his longtime friend and confidant’s happy place. In fact, Zaki’s last solo music video, Tumhari Aankhon Mae was also shot at the same facility. “Zaki never needed any studio shifts. He would just come and occupy the studio and everyone else would let him do it out of respect,” Emu remembers.

The Fuzon leader says Zaki always came by to have a good time and never to make a song. A lot of times he would end up recording something so incredible that Emu and the staff would be at the edge of their seats to see the final product. But Zaki wouldn’t care a dime.

“I remember he had recorded an amazing blues solo on an original melody and it gelled together really well, but he never finished it. I had to beg him to take interest and eventually he agreed by saying, Acha tu khud khatam kar kay kuch bana dae iska (Just finish it yourself and send me the final project),” recalls Emu.

That shouldn’t be confused for a false sense of modesty or a lack of dedication, Emu is quick to elaborate. If he really got into something, Zaki would work day and night to make it possible and be disappointed if it didn’t get the response he expected. “That childish anticipation of unwrapping a gift stayed with Zaki through his final days. Yes, he had become sadder and more hopeless but music still moved him.”

Zaki recorded a lot of music at Emu’s facility. A look through all the archived folders shows another version of Street Signs in which Zaki himself has sung the song. A refreshingly upbeat, pop but bluesy number called Jab Zindagi was nothing less than a discovery. Although the song was recorded in June 2015, when many believe Zaki had passed his prime as a singer, his vocals sound so crisp that one is compelled to think that Zaki really needed to be in that ‘zone’ to deliver. There are also some loose jams that Emu seems most excited about sharing.

“Every time, we musicians got together to play, I just used to press the record button. Guess what, Zaki is a part of those jam sessions too. There’s one in particular jam where Jason Anthony from Aaroh is playing the drums, I am on the keys and Zaki is playing the guitars. So hopefully I’ll put it out there soon,” says Emu.

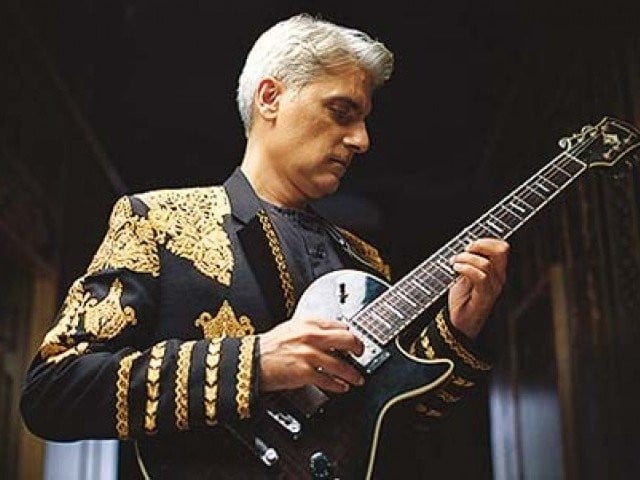

PHOTO: FAYYAZ AHMED

PHOTO: FAYYAZ AHMEDThe magnum opus that never was

Zaki’s final and most elaborate recording took place at Emu’s studio. It was an Arts Council London project that he and his collaborator and close friend Sarah Sarhandi had collaboratively worked on.

In the final four years of his life Zaki had grown close to British-Pakistani musician Sarah Sarhandi. Sarhandi is a well-known British composer and violist who Zaki first heard in 2013 and immediately approached for collaborative projects.

Together they formed an explosive duo that revamped Minuet in G by Johann Sebastian Bach, calling it Dotted Waltz. They also worked on the score for a Polish film, which ended up being showcased in a Polish museum for two months. These projects were punctuated by a lot of experimental music, both eastern and western classical.

In the meantime Sarhandi received a grant from Arts Council UK/British Council (Artists International Development Fund) in March of 2015 for a collaborative project in Pakistan with Zaki. Their first live performance was scheduled to be held on April 27, 2015 at The Second Floor (T2F). On April 24, Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead. Zaki’s streak of misfortune hit a new low, as the scheduled performances never took place.

“Sab achay log marjaayngaay (All the good people will die),” Zaki told me over the phone the very next day. He was sad for his loss but sadder for Sabeen.

But Sarhandi’s presence around him had really made him positive about life and helped him do something beyond mediocre, which he believed the industry demanded. “What I am doing right now is a lot deeper than pop music,” Zaki had told The Express Tribune in a 2015 interview about his collaboration with Sarhandi. “I feel my full potential is being utilised and it’s very liberating.”

As luck would have it, Zaki passed away in 2017. Making industry insiders and aficionados curious about his guitars and remaining music. While Zaki’s friend and collaborator Fayyaz Ahmed bought some of his guitars from his brother Shahid Zaki, the question around Zaki’s hard drives and other software remained unanswered. Speculations were rife that the hard drives were either stolen or lost. Some even thought that he burned down the hard drive along with some of his guitars during a breakdown. Turns out, these are just stories, improvised about a person few knew that well.

The mythical hard drive

His hard drives are with Sarhandi who permanently lives in London. She has been close to Zaki’s family and was in his apartment with them in the days following Zaki’s untimely demise. “It was Aamir who personally instructed and entrusted me to take care of his music, material and legacy in the event of his death,” Sarhandi writes from London. “His brother Shahid honoured Aamir's wishes and personally gave me all the material.”

Away from the music scene in Pakistan, Sarhandi has been working towards ‘appropriately’ sharing Zaki’s legacy with the world, including his unreleased music. “I have been speaking and consulting with several close contacts/colleagues of Aamir's and of mine in both Pakistan and the UK about this,” says Sarhandi while adding that she aims to be in Pakistan in August, hopefully with some answers.

Some of this music, Sarhandi and Zaki created together was previewed at the Alchemy Festival Southbank London in May 2016 as part of her performance 'Both Universe'. The project was supported by several charities such as Rangoonwala ZVM Foundation and Arts Council England, and Zaki's fees for composition and performance were sourced from Habib Bank Limited through Pakistan High Commission London. “All these organisations were extremely excited and proud to bring Zaki as a very senior and respected Pakistani musician to the UK and to introduce him to a wider audience,” shares Sarhandi.

Sadly Zaki's visa didn’t arrive on time for their collaborative performance in London. He did appear by video and his recorded guitar parts were featured in the performance in which a number of highly acclaimed musicians also performed.

“Up until his death, Zaki was very excited about this music and his direction whilst completely honouring and taking pride in his roots in Pakistan,” remembers Sarhandi. He looked forward to taking his music and sound to the wider world as well as joining hands with the new musicians and artists they had collaborated with in the UK, Europe and the US.

At the end of the day, like everyone else, Sarhandi remembers Zaki as a musician who wanted more people to listen to his music and a person with a heart of gold. “Aamir as is known suffered from Bipolar Disorder, a disease caused by a chemical imbalance of the brain. He was not mad. The only drugs he took were medically prescribed. He was, in the years since we met, under constant medical supervision,” says Sarhandi.

She believes that despite the serious difficulties Zaki faced from the side effects of the medication and episodes of mania and depression caused by his condition, he worked tirelessly on new music up until his death. He was concerned above all to create music that drew on his immense experience and always pushed boundaries.

As I conclude this story, it is reassuring to know that another hard drive that belonged to Zaki is currently with a forensic IT expert in London. For now, it appears it does not feel like powering up. Isn’t that something you would expect Zaki to pull off? Just saying.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

1725885571-0/Tribune-Pic-(9)1725885571-0-165x106.webp)

1731563250-0/Express-Tribune--(1)1731563250-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ