PHOTO:FILE

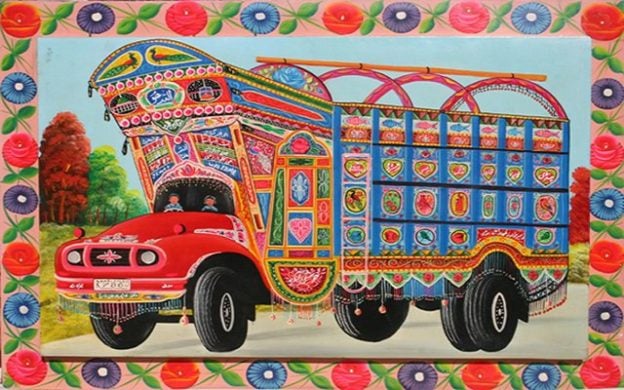

PHOTO:FILEIn fact, I definitely didn’t think of it as “art” at all. It was simply something I found around the city, like wall chalking or electricity poles, or donkey carts. None of these are considered “art” and neither was “truck art.” At least such was the case while I was growing up in the early 90s. So what changed? Perhaps, the post-modern discourse.

PHOTO:FILE

PHOTO:FILEA discourse is a way of viewing reality. Post-modern discourse originated around the mid-20th century in Europe. It was identified by its opposition to traditional western discourses of Christianity and the Enlightenment, particularly against their claims to universal truth i.e. both Christianity and modernity claimed to be based on absolute, objective truths. Additionally, both Christianity and Enlightened Europe argued themselves to be superior to other cultures or religions of their respective times (hence the justification for colonisation). By the mid-20th century several devastating critiques of these claims had emerged and were enough to form a consensus (albeit not unanimous) among western intellectuals on certain fundamental points. These included:

- All truths are relative to culture and history and none of them are permanent or objective. Therefore, there can be no universal claims to truth.

- Since each culture is born out of historical contingency, and since all its beliefs, values and practices are only culturally specific (thus, only relevant itself), no culture can be superior or inferior to another.

- Since all cultures are equal, one should appreciate each other’s’ differences and the beauty of diversity they contribute to the world.

I believe that today, this post-modern way of looking at reality has proliferated into the Pakistani arts and culture scene as well. Suddenly, things we took for granted, as being ordinary parts of our lives, have become aesthetic objects representing our identities and roots.

Naya Pakistan, purana VIP culture: FIR registered against citizens for impeding president’s protocol

The irony of this situation is best portrayed in Coke Studio. The show’s usual formula of producing music is to take a native, cultural or “original” piece of music and fuse it with modern elements to create some nice, postmodern-friendly-diversity-affirming (with a pinch of western pop, rock, jazz etc.) songs. But in the process, our artists and producers (the bourgeois?) forget one minor detail: the very framework of post-modernism (celebrating one’s own roots and appreciating the richness of other native cultures) is strictly western.

PHOTO:FILE

PHOTO:FILEThis can be seen not only throughout contemporary Pakistani music but also in other cultural fields. A good example of this is fashion, where post 9/11 we saw a surge of consumerism in local dresses (shalwar kameez, kurtas and saaris etc.) We now even have a shampoo ad for the women wearing the hijab, as well as Dettol soap with the essence of ittar.

We no longer live in an age where speaking fluent English or wearing western clothes are considered symbols of social status. Today, in order to be western, you have to celebrate your own culture, folk songs, dances, dresses etc. In other words, being western today means celebrating cultural diversity and romanticising marginality. Even the return to religious origins (the contemporary fascination with fundamentalism or mysticism, for example) is strictly post-modern, and hence western, nostalgia.

PHOTO:FILE

PHOTO:FILEIt is often said that Pakistan suffers from an identity crisis. I agree. But to conscientiously try to be more “local”,” native”, “spiritual” and “natural” - in other words, "oneself" - is only exacerbating this crisis. What if we, as a nation, first acknowledged that we aren’t (and maybe never were) completely “original” - whatever that means? What if alienation from one’s culture is an authentic experience of culture itself? What if we drew inspiration for our art from this very crisis, rather than try to resolve it?

Bio: Moonis Azad is a lecturer at the Department of English Literature at Karachi University.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

1732687571-0/Untitled-design-(2)1732687571-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS (3)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ