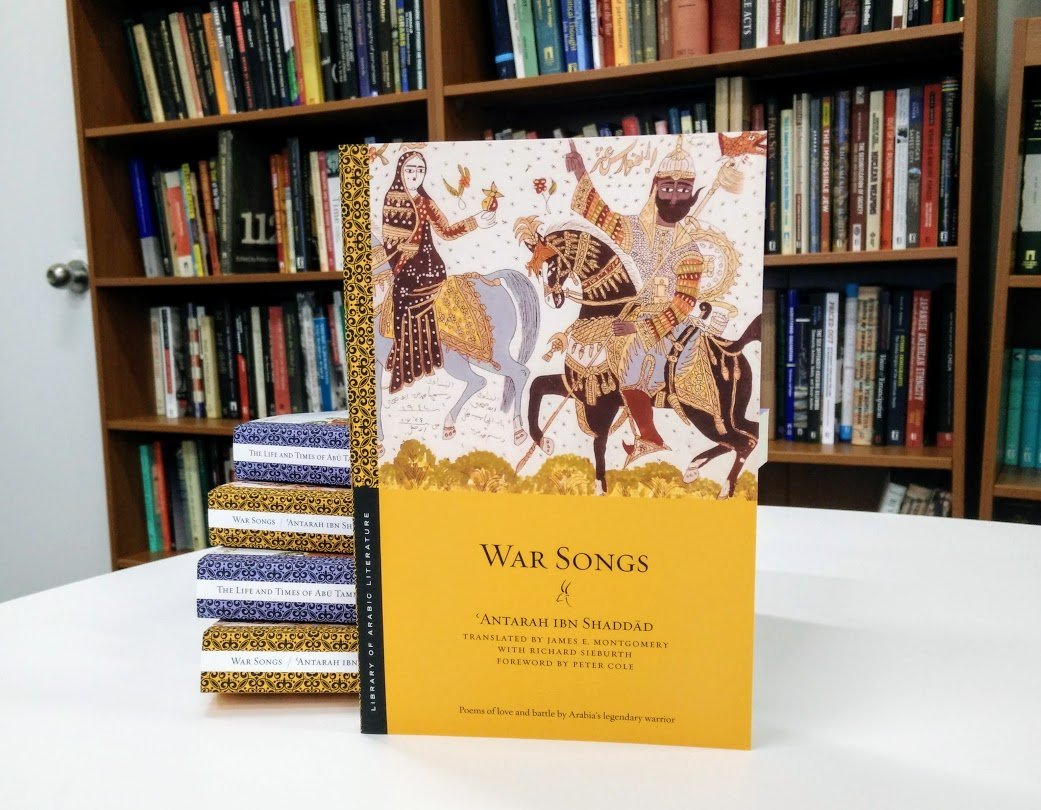

The translated works of warrior-poet Antarah Ibn Shaddad were published by New York University Press in October and are available for sale worldwide in bilingual and English-only editions.

According to James Montgomery, who took seven years to meticulously reproduce the poems composed in sixth-century Arabia (known as the age of ignorance in the Islamic world) for audiences in the twenty-first century, the book aims to introduce Arabic literary heritage to readers in the west.

In Iraq's city of bookshops, theology and poetry rub spines

Antarah Ibn Shaddad was born in Najd, modern-day Saudi Arabia, to an Arab father and a slave woman of Ethiopian descent. Legend goes that he earned his freedom through exploits on the battlefield, and became a feared warrior. Antarah also fell in love with a woman named Ablah, but could not marry her owing to his lowly position in society. The poems composed by him often touch on topics such as love and separation, or courage and heroism in battle, drawing on personal experiences. His work also forms part of the Mu'allaqat, a set of seven poems thought to have been hung at the Holy Mosque in Mecca before the advent of Islam.

Montgomery teaches Arabic at the University of Cambridge and is an executive editor of Library of Arabic Literature at New York University, Abu Dhabi. The celebrated academic sat down with The Express Tribune at Sharjah International Book Fair to discuss Antarah Ibn Shaddad and the importance of words and ideas.

"The project started when a Hollywood producer contacted New York University to inquire whether the institution would be interested in translating a part of the poetry composed by Antarah Ibn Shaddad for merchandising related to the release of a film on the famous warrior," the professor said when asked about the story behind the book.

Arabic language can unite Muslim Ummah

"The producer wanted to cast Dwayne (The Rock) Johnson for the movie, but the project was cancelled before it could come to fruition. However, NYU decided to continue with the translation and I jumped at the chance to lead it when the opportunity came up," he added.

Parts of the interview with the academic have been reproduced below for interested readers.

In conversation with James Montgomery

Library of Islamic Literature translates texts from the pre-Islamic era to the emergence of the modern Middle East. Why have you chosen to concentrate on this particular period?

There are already a number of ventures which cover modern Arabic literature, and a number of important publishers sponsor translations of modern Arabic literature, but anything before the nineteenth century is just not covered. So I felt there was a complete absence of material and translations there, and wanted to supplement that.

What about the Arabic literature before the sixth century?

The library aims to translate from the earliest appearance of Arabic in Arabia in the Jahalliya (age of ignorance) poetry. So before that, there is nothing that is genuine or verifiable Arabic literature. There are stone carvings and things, but little else. So we select works from the first appearances right up to more or less until 1920, which is roughly the time period in which our latest book was written.

What is the difference between the translations for the bilingual edition and the English-only paperback?

The translations are the same. We begin with the Arabic-English hardcover, and out of this, we take the Arabic and turn it into PDFs, and they are available on the website. Then we take the English and format it for the paperback. We commission a new foreword, but the translation remains the same, except that any reference in the book which relates to the presence of Arabic is removed.

What is the difference between different types of translations, for example, free-style, literal and adaptive?

Strict literal translations would be something that seeks to retain the structure of the Arabic writing as far as possible in the English edition, and so this translation would try to replicate Arabic syntax and Arabic grammar, as well as Arabic vocabulary, in English.

The library wants translations that will be comfortable in English, so that if you are someone who knows nothing about Arabic whatsoever, you can pick the book up and not feel that you are missing a whole body of knowledge that you do not have. So it wants the translations to be as comfortable in English as possible.

There is also a third type of translation, which is more adaptive. In this, the translator tries to follow Arabic into English but leaves the Arabic slightly further behind.

The character of Antarah has also been published as a graphic story by the company COMICS. PHOTO COURTESY: ARABLIT

The character of Antarah has also been published as a graphic story by the company COMICS. PHOTO COURTESY: ARABLITWhat topics does Antarah cover in his poetry?

The thing about Antarah is to think about him like we think about King Arthur. So he was probably a historical person, but everything we know about him is more legend than history.

The legend is that he was born as a black slave to a black slave mother who was the concubine to an Arab, and according to the custom at the time, if you were born a slave, you remained a slave for the rest of your life, until your father decided to give you freedom.

One day, when the tribe was attacked, Anatarah's father asked him to join the fight. But Antarah declined, saying slaves are only good for milking camels. His father then proceeded to offer him freedom in return for his participation, and that is how Antarah won his freedom.

So the story is a classic story of this outsider in society, someone who wants to belong, but is also angry at the fact that he needs to make the effort to belong.

How does Antarah relate to the world of today?

When I talk to my children, who are all in their twenties, the one topic of conversation which always comes up is identity, it is belonging in society, it is respect, and self-worth, or the creation of a society that is open for everyone to participate. We might not think that Antarah’s solutions, like the one on the battlefield, are the ones that we want our children to espouse, but nonetheless, the issues that he is dealing with are universal and very contemporary. Here you have someone who is using the only means that you know he has at his disposal in order to gain the recognition that is denied him.

How do readers from the east and west perceive Antarah differently?

I would say that the person who already knows Arabic, and who is familiar with Antarah, does not need the translation. And if it were up to me, any language that I know, I would rather read the work in that language and not in the translation.

Certain elements of Arabic literature do not seem particularly relevant to teenagers today, and by translating them into English, we are telling teenagers that these are important works. So the translation of the Arabic into English also shows the Arab children that their heritage and history is important.

For someone from the west who is introduced to Antarah for the first time, this is like Beowulf fighting the dragon Grendel, or someone from Greek epics. So they can immediately relate sixth century Arabia to the tradition that they are familiar with.

And what I wanted to try with the book was to make this possible, because there is a certain thing that happens, when you tell someone that you have a selection of old Chinese poetry, and you would like to give it to them, they thank you. If you say to someone, I have got a translation of old, Arabic poetry, they somehow feel surprised, shocked, or anxious. So something like Chinese is more familiar to the western audience than something from the Arab world, in the way the people imagine themselves in the west.

So what I wanted to do was to take away all that anxiety, I wanted to say that this is Arabic, but it could have been old English, or ancient Greek, Latin or any language whatsoever. Forget about the fact that it was Arabic, and just concentrate on the work.

James Montgomery. PHOTO COURTESY: LIBRARY OF ARABIC LITERATURE

James Montgomery. PHOTO COURTESY: LIBRARY OF ARABIC LITERATUREDoes Antarah take inspiration from the epics of antiquity?

No, definitely not.

What about his influence on writers after his time?

Antarah’s most famous poem is the Mu'allaqat. That is one of the most famous and central poems in the whole of the Arab tradition. And in fact, we owe the existence of Antarah’s poetry to two scholars working in Islamic Spain in the twelfth century. They wrote commentaries on the poetry five hundred years after it had been composed. They were very learned scholars from Granada who were able to see the relevance of the poetry to their own time and society.

How was your experience translating this book?

This translation took me seven years. If I had wanted to do the translation we were talking about earlier, I could have done it in six months. But I wanted to work on it and make sure it communicated to readers, almost immediately I had lots and lots of starts and false starts. Some of the poems I translated more than ten times, sometimes the poems would not work on the page, or did not sound right in English to my ear, but eventually, the advice and help of a friend who is a translator of French and German helped me get through it.

Are you happy with the final translation?

When I picked up or opened the books, I was almost as proud as the day my children were born. This meant so much to me over the seven years, and it means so much to the project we are working on. We have organised readings of this book in London, New York and Sharjah.

Library of Arabic Literature

The Express Tribune also talked to Chip Rossetti, who is an editor at Library of Arabic Literature and has extensive experience translating Arabic texts into English.

According to Rossetti, the library was started in 2010, and first started publishing books at the end of 2012. It is supported by the New York University in Abu Dhabi and published by NYU Press, New York.

Walk held to promote Arabic language

"Texts from a variety of genres, from literature, poetry, travel literature, philosophy, Islamic jurisprudence and history, are translated and published in bilingual editions, with Arabic on one side and English translations on the other side," he said.

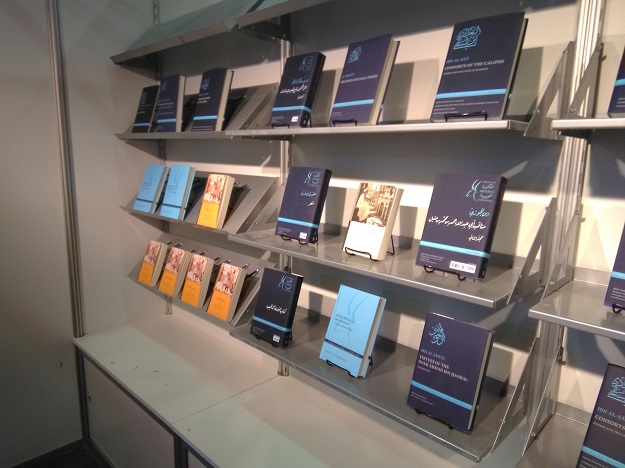

"All the works are translated by scholars from Arabic and Islamic studies. The library is now in the sixth year of publication, and has 32 hard covers out, bi-lingual hard covers. There are also 19 English language paperbacks, which are brought out a year or two after the hard cover comes out."

Responding to a question about the nature of the translations, the editor outlined that the library aimed for a modern, lucid English translation for Arabic texts.

"Some of these texts were partially translated in the nineteenth century by orientalists in Europe and are now very outdated. They do not always convey the beauty or importance of the Arabic language," he added.

Asked about the process which went behind the publication of a book, Rossetti underlined that the library worked with a very small pool of academics who specialised in pre-modern Arabic, which meant that they had the level of expertise to translate the texts in the right way.

"The library has a proposal process where it works closely with scholars who propose texts to us. It is a very long process with multiple reviews and quality control."

The collection of books on display at Library of Islamic Literature stall at Sharjah International Book Fair. PHOTO: EXPRESS

The collection of books on display at Library of Islamic Literature stall at Sharjah International Book Fair. PHOTO: EXPRESSAccording to the editor, the translation was a collaborative process. "The idea of a translator going into a room and producing a translation alone does not really work. The more people that have input, and the more people one can bounce ideas off, the better the translation is going to be."

Rossetti further revealed that the library was planning on publishing the translated works of famous Arab scientists and philosophers as well.

"One of the great difficulties in translating the books is that they are published as much for scholars as they are for general readers. So we have to pay attention there to producing translations which work for both, scholars who have deep knowledge of the texts already, and those who are reading it for the first time."

James Montgomery and Chip Rossetti also held a session at the book fair to discuss the book with local academics and students. The session included a moving recital of the translated poems by Montgomery, as well as a question and answer segment with the audience.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ