President Xi’s domination promises stability

Extending Mr Xi’s tenure will ensure some measure of predictability in one way at least

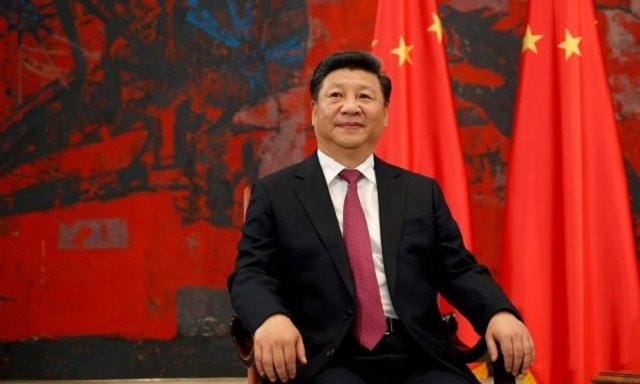

China's President Xi Jinping PHOTO: REUTERS/ File

Most significantly, Trump has begun to move against the system of international commerce built painstakingly over the last several decades. Within a year of his residence in the White House, Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement negotiated by Barack Obama, his predecessor. He has decided to impose stiff tariffs on the import of solar panels, steel and aluminium. The North America Free Trade Area is being negotiated and there is fear that the United States may walk out of this as well.

The Trump administration has also introduced great uncertainty in the area of immigration. He has shown a strong preference for admitting people from predominantly white countries and that means northern Europe, Australia and New Zealand. He used strong and vulgar language to describe blacks who have come into his country and the countries from which they have come.

The Chinese are moving in the opposite direction. By giving President Xi at least one more term, certainty and stability could be expected from the direction in which Beijing was proceeding. “Extending Mr Xi’s tenure will ensure some measure of predictability in one way at least: by allowing for resolute policy making,” wrote Mary Gallagher in an article published a few days after it came to be known that President Xi will not be leaving his position anytime soon. She is the director of the Lieberthal-Rogel Centre for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan.

Some scholars of authoritarianism divide dictatorships into two categories: institutional and personal. The first operates through committees, bureaucracies and something like consensus. The second runs through a single charismatic leader. Maoist China, Stalin’s Soviet Union and now Putin’s Russia are some of the obvious examples of the second. Deng Xiaoping’s political reforms were moving China into the first category. Will the grant of additional working life to President Xi take China back to the first category? The answer is not necessarily so.

Even those Chinese scholars not working for government institutions believe that the new economic reality and the enormous changes in the global system require China to make massive political and economic adjustments. These may not be possible in a relatively slow-moving decision-making system based on consensus-building. The Chinese system may revert to the institutional category once China has developed a new economic model and redefined its role in the still-forming international system that calls for new power-sharing arrangements among the world’s major powers. Xi has said that he would like to work with the United States, still the world’s largest economy, but in the context of internationally agreed legal framework. That is not where Trump would like to take his country.

But authoritarianism of the personal variety is harder to maintain. According to Erica Franz, a scholar at Michigan State University, personalisation is not a good development. There are subtle downsides that lead to long-term instability. Domestic politics then become more volatile, governing more erratic and foreign policies more aggressive. If her research is correct, the Xi manoeuvre purchased to provide stability over the short term to make some necessary adjustments to changing situations might, in the end, will yield long-term instability. This may result from people’s aspirations for greater participation.

In 2005, political scientist Bruce Gilley struggled with one of the most important questions for any government: Is it viewed by its citizens as legitimate? He came up with a numerical score, determined by sophisticated measurements of how the governed behave. He found then that China enjoyed higher legitimacy than many democracies and every other non-democracy. This work was done when China was concluding the first phase of its remarkable economic progress. In the preceding quarter century, its national income had increased 32-fold and income per head of the population 25-fold. But with the Great Recession of 2007-09, China’s economic fortunes changed along with the rest of the world. Gilley revisited his model in 2012 while the global economy was still in the recovery mode.

Economic slowdown was not the only problem the country faced. When Xi Jinping took control of the party in the fall of 2013 and became the country’s president, he was aware that he had to deal with another problem. ‘Elite capture’ is the term used in economics and political science for the situations in which those who have access to power use it to satisfy themselves rather than the general populace. There was considerable elite capture going on in China when Xi was handed the reins of power. There was obvious discontent in the country. This could pose serious challenge to those in positions of power.

Recognising this, Xi and his associates decided to tighten their grip on the political system while moving decisively against corruption. By the spring of this year, President Xi felt strong enough to change the Constitution and prolong his stay in power, arguing for continuity in the process of governance that he had instituted.

This retreat into authoritarian politics in China is occurring at a time when several other parts of the world are also moving in the direction away from open, liberal political systems that allow for full participation of all people. But it is in global economics that Xi’s influence will be greatly felt.

Published in The Express Tribune, March 12th, 2018.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ