The real reason to worry about Italy’s election

Sunday’s vote more likely to result in a hung parliament than rather than a disruptive new government

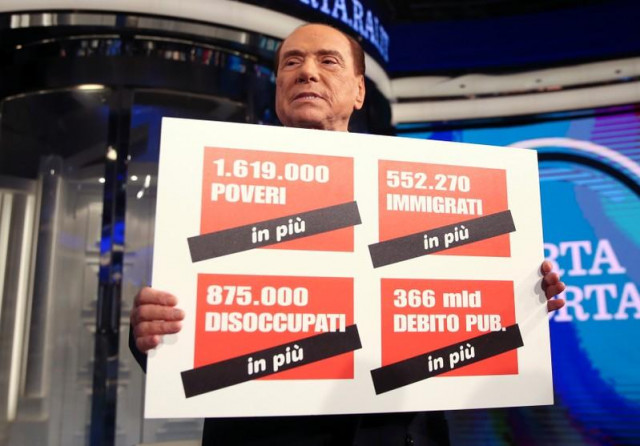

At a television talk show taping in Rome during the run-up to Italy's March 4 general election, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi holds up a poster warning voters of increasing poverty, immigration, unemployment, and public debt. PHOTO: REUTERS

It is possible to predict a political horror story because the ruling center-left Democratic Party, which is pro-European and broadly reformist, has fallen out of favor. One rising force in Italian politics promises disruption. Many Italians will back the insurgent Five Star Movement, which is noisily anti-establishment. A reviving political force will be scarcely more palatable, as Silvio Berlusconi, forced out as prime minister in 2011, makes an unexpected comeback. Though Berlusconi is currently barred from seeking public office, his party is part of an alliance that includes the Northern League, a euroskeptic group. This right-of-center coalition has been polling strongly on a program that would loosen the budgetary reins and dial back on reforms.

Lucia Annibali: from acid attack victim to Italy parliament candidate

Yet the risks posed by politics in Italy are usually exaggerated. The governing class is adept at extricating the Italian state from tight spots. When Matteo Renzi, who proclaimed his reformist credentials as the “rottamatore” (demolition man), had to resign as prime minister at the end of 2016 after losing a referendum on constitutional reform, there was consternation at first. Yet all that Renzi had succeeded in demolishing was his own grip on power. There was a smooth transition to Paolo Gentiloni’s premiership, which has been quietly effective over the past year or so.

At other times Italy has formed governments with ministers drawn from outside politics that have proved viable and effective. The one formed in the mid-1990s pushed through a big pension reform. More recently Mario Monti was drafted in to replace Berlusconi as prime minister in late 2011 when tensions about Italy in the euro crisis were at their height. Monti’stechnocratic government pushed through an unpopular program of austerity and reforms, which fended off the market pressures on Italian sovereign debt that had raised 10-year bond yields to an unbearable 7 per cent.

Sunday’s vote is more likely to result in political paralysis arising from a hung parliament than either a disruptive new government or a further resort to the technocrats. A parliamentary stalemate would be undesirable but it should be manageable. The political horror story will turn out to be just that: a story.

But if there is too much angst about Italian politics, there is too little about the economy. Investors are placing excessive faith in the current business upswing. That strengthened last year as GDP grew at its fastest clip since 2010. Yet the growth was only 1.4 per cent, below even Britain’s Brexit-battered 1.7 per cent and well short of the euro area’s 2.5 per cent (the highest since 2007). Unemployment fell from 11.8 per cent of the labor force at the end of 2016 to 10.8 in December 2017. That still leaves it well above the euro area’s average of 8.7 per cent, let alone Germany’s 3.6 per cent.

Whatever the strength of the current upturn, it comes after a dismal decade for the Italian economy, which still bears livid scars from the deep recessions arising from first the financial crisis and then the euro crisis, followed by a weak recovery. Italy’s GDP in the final quarter of 2017 was almost 6 per cent less than at its pre-crisis peak in early 2008. By contrast the euro area’s output was 5.5 per cent higher and Germany’s was up by 11.5 per cent.

Berlusconi suggests Italian general could be next prime minister

Italy has not simply lost ground over the past decade. Its poor economic performance over so long a period has left two unwelcome legacies. First, Italian public debt has risen from an already high 100 per cent of GDP at the end of 2007 to over 130 per cent, a burden on the economy exceeded in Europe only by Greece. Second, bad loans have built up in the banking system as businesses hurt by the ailing economy have been unable to service them. Italy’s pile of non-performing loans is the biggest of any country in Europe, making up almost a quarter of the total in the EU.

These twin burdens hobble the economy and make it susceptible to any setback. Banks weighed down by bad loans are reluctant to lend, stifling the flow of credit to new enterprises and projects. Italy’s huge public debt means that it simply cannot afford a big rise in long-term interest rates, which are currently at a benign 2 per cent largely thanks to the European Central Bank’s (ECB) massive program of quantitative easing that has created new money to buy bonds.

Banks are now making progress in reducing their bad loans, but further inroads depend crucially upon an extended period of strong growth. That is also vital in order to bring down the public debt burden. Yet even before the financial crisis Italy’s underlying growth rate was sluggish, held back by limping productivity. That is why, remarkably, living standards measured by real GDP per person were 5 per cent lower in 2016 than in 2000. By comparison, they were nearly 20 per cent higher in Germany.

For the moment, the Italian economy can enjoy its spell in the sun of the ECB’s easy-money policies. But the ECB is already starting to turn the heat down by reducing the scale of its asset purchases. The cyclical upswing has masked the underlying fragility of the Italian economy and public finances. That vulnerability will persist whatever the outcome of the election.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ