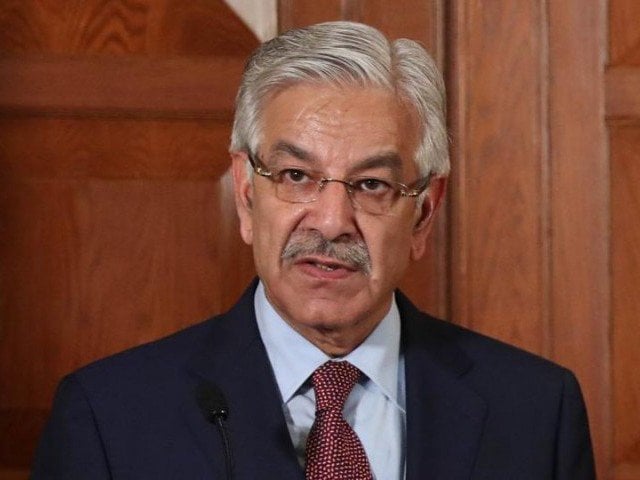

And the drastic shift is most certainly there. In the rarest of events, last year, a military delegation from Russia was given a quite exclusive tour of Waziristan by the Pakistan Army, reportedly. Almost a week ago, the Foreign Minister of Pakistan, Khawaja Asif, stood beside Sergey Lavrov, the foreign minister of Russia, as Lavrov affirmed support for Pakistani counterterrorism efforts at a time when almost all of its traditional Western allies were pushing to put Pakistan on the terror financing watch list.

But again, the foreign policy lies in the signposts.

Signposts in Pakistan’s Waziristan, formerly a hotbed of militancy and currently under the safe keep of the Pakistan Army, read in English and Urdu of course but also in Chinese and in Russian. The road signposts point towards local cities of course, but also towards Khunjerab and further north towards Tashkent and ultimately Moscow.

Financial Action Task Force correctly faults Pakistan

Excluding a few insignificant periods of cooperation between the two nations, the relations between Russia and Pakistan have been largely cold and even hot when Pakistan found itself on the frontline of the fight against the Soviets in Afghanistan, once again at the behest of the Americans.

Now, however, the signposts in Waziristan point towards Moscow in Russian; cooperation between Russian and Pakistani establishments is at an all-time high, most importantly with respect to Afghanistan. And Pakistan as it spirals out of the US control continues to look east, first to Beijing and now to Moscow. For all intents and purposes Pakistan’s shift eastwards to its all-weather ally in Beijing and now, as Russia warms up to Pakistan, further north to Moscow, is in lieu of traditional support it has received from capitals in the West, most significantly from Washington.

What has sparked this new warmth in the Russo-Pakistani relationship is no secret, however ironic it may be, considering it is the US. But there’s more to this new alliance. It’s not just that the US has pressured Pakistan into looking towards Moscow and Beijing, Pakistan’s relationship with the US has almost always featured the former bending to consistent pressure from the latter to ‘do more’. Perhaps never more significantly than in 2001 when then president Pervez Musharraf responded to American threats of being bombed “back to the stone ages.” Pakistan had then submitted to almost all American demands, essentially becoming part of the US invasion of Afghanistan.

This time around the US is back with its pressure tactics with cutting its military aid, holding back other kinds of cooperation and publicly condemning Pakistan on the global stage. A recent flashpoint perhaps was when the US led its allies in an effort to put Pakistan on the FATF watch list. In what is now characteristically Pakistan’s new foreign policy however, Pakistan instead of engaging its estranged friends in Washington, called upon its all-weather allies in Beijing, Riyadh and Ankara, as it faced off against the US. And this is what has changed significantly, while Pakistan’s new relationships may be the symptoms of estrangement with Washington, the American pressure is nothing new, in fact, the only thing that has changed is Pakistan’s willingness to face off against that pressure from the US.

Foreign policy: Tumultuous and eventful 2017

Since the Trump administration came to power, Washington has had an exceptionally tough stance on Pakistan with the US president accusing it of “lies and deceit.” The policy with Pakistan has been received with equal amounts of incomprehensible shock and pleasant surprise in different parts of the world, as the US emphasised it required Pakistan to do more against militants in Afghanistan that were purportedly getting support from terrorist elements hiding in Pakistan.

But with what is now being called the ‘Bajwa doctrine’, in reference to the current Chief of Pakistan Army, Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa, Pakistan seems to be much less reluctant, when push comes to shove, to face off against the US pressure. Pakistan has decried publicly American condemnations of Pakistan’s attitude towards militancy in Afghanistan, claiming it has done its part to save Afghanistan often at the cost of its economy and stability. With the US asking Pakistan once more to ‘do more’, Pakistan this time is saying, it has done more than enough. And so, as the US ratchets up the pressure on Pakistan through tools like the FATF, Pakistan instead of responding to American pressure as it has done historically has chosen to resist the pressure with the support of its new friends. While it is important that Pakistan balances its sovereignty and interests against American pressure, it’s worth questioning if it is simply the advent of new friendly power centres that is encouraging Pakistan to dump its traditional ally.

Surely enough, Pakistan survived Washington’s attempt to humiliate it at the FATF with the support of its (other) friends. However, having failed in its latest attempt to put pressure, the US is not likely to give up any time soon. And therein lies the question, whether Pakistan’s decision to singularly resist American demands and pressure, and resort to a paradigm shift in a decade-old foreign policy is really Pakistan’s only good choice.

The risk is isolation, with Pakistan and the US engaged in a high stakes ‘who blinks first’ standoff. It is important that in the power centres of Islamabad and Rawalpindi a significant relationship is not considered to be dispensable simply due to the existence of other avenues of support. While warming up to Moscow is a belated success for Pakistan’s foreign policy, losing a traditional ally like the US voluntarily would be a foreign policy failure, the trick in foreign relations is to be good friends with as many, while having as few enemies, as possible.

Pakistan has historically had a distinctly binary foreign policy as it raced to pick sides in conflicts, most notably the Cold War, when other states chose to stay non-aligned. A thought process where the US is either thought of as the closest ally, or an enemy, would also be binary and thus ill-advised. What is required is for Pakistan and the US to engage in multi-dimensional foreign policy to salvage an undeniably significant relationship. It is important for Pakistan not to determine the fate of future relationships at the expense of existing ones or vice versa. As Pakistan moves to resist American pressure, it is worth questioning how far this resistance would be advisable and justified and how historical relations between not just the US and Pakistan but its traditional Western allies, who moved FATF against Pakistan recently, are balanced with other interests. The opposite is certainly true for the US and the question has been put to them by Islamabad as it chooses to ask of the Americans how much they value their relationship with their former close ally, which remains indispensable in America’s longest war effort.

Published in The Express Tribune, March 1st, 2018.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

1722586547-0/Untitled-design-(73)1722586547-0-165x106.webp)

1732326457-0/prime-(1)1732326457-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS (7)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ