Young musicians break barriers, lead cultural revolution in South Waziristan

They say besides Taliban, conservative values of the tribes are as much to blame for the threats to performers

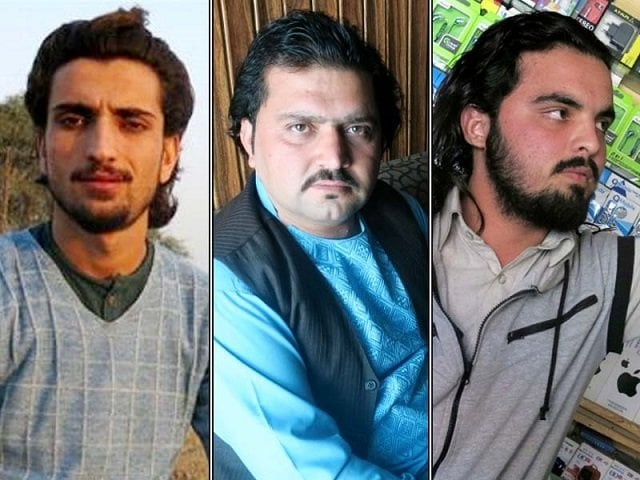

They say besides Taliban, conservative values of the tribes are as much to blame for the threats to performers. PHOTO COURTESY: ALJAZEERA.COM

Maqsood Rehman, a 22-year-old talented youngster from Sarwakai village, sings a combination of traditional folk songs, modern pop songs and self-described “revolutionary” anthems as he wants to bring his people back towards their musical roots.

“My songs are often on these themes: on unity, talking about how our people should once again come together and should become self-aware. I want to deliver a message, of peace, unity and education,” said Rehman while speaking to Al Jazeera.

He always had a beautiful singing voice, and was often called upon to lead students at his primary school in their morning rendition of the national anthem.

However, a Taliban ambush on his school in 2005 changed everything for the 10-year-old Rehman and his school friends.

“[The Taliban commander] gave a speech, saying that the army was coming. As they were speaking, explosions began to happen all around us. […] they hit the homes around us, we could hear the screams,” he said.

Wracked by fear and anger of the brutal attack, the young Rehman was left to question his priorities in life. He said he started writing poetry after the terrorist attack, thinking he needed to do something for the country, and for the people of Waziristan.

The Taliban are defeated, but their minefields continue to bleed South Waziristan

The young musician has held several large concerts in Dera Ismail Khan, as well as making television appearances on local Pashto-language stations. His audience, he said, is mostly made up of young people.

Before the Pakistani military launched an anti-terrorism operation in the area in 2009, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants ruled South Waziristan and parts of adjoining districts with an iron fist, banning all musical expression and even shutting down barbers who would shave men’s beards, deeming the practices un-Islamic.

However, that did not stop youngsters like Rehman to keep the flame burning and expressing their thoughts through poetry and music.

“If someone in our area heard that I was a singer, back then people would really look down on me, and I might even have been killed. That's how difficult it was,” said Rehman, who is currently based in the more developed district of Dera Ismail Khan, about 110km east of Sarwakai.

He has been training in music for the last two years, trying to find a way to express his poetry to the world.

Rehman’s passion for his people and his music is evident in his broad smiles, and often, when he speaks of his work, it is difficult not to be infected by his contagious energy.

He said the first thing terrorists attacked was culture and that is what divided people in the area.

While South Waziristan is known for its conservative values, music has played a central role in the culture of the Mehsud and Wazir tribes, which dominate the area.

“Our attan [a folk dance] was based on unity, it would bring people together. We would also have the cheegha [a village-wide call], to gather people together in a group to resolve internal disputes. If we ever had disputes with another tribe, they would also be resolved this way, and the attan was a way of unifying people [to cement that resolution],” he said.

However, during Taliban’s rule, that culture slowly began to fade, and the dhol [drums] fell silent, he added.

“Music was banned for 20 years, but now people are coming back towards this. There is a huge demand.”

Conservative values

Shaukat Wazir, another talented young musician from Wana however believes that Taliban were not the only threat to performers from South Waziristan.

“I don’t see any difference in the time that the area was under the Taliban and today’s situation,” said the 28-year-old former potato farmer.

Wazir used to stage secret concerts when the area was under the control of the Taliban. He bought his first keyboard off the back of a smuggled vehicle when he was 16, managing to escape Taliban attention because “they thought it was a kid’s toy”.

He made his first recorded album -- a mix of folk songs, attan tunes and Pashtun nationalist anthems -- in 2016, long after the militants were driven out of the area.

“When my album was released, I could not go to my area for four or five months. When it was released, I saw that the attitude of people [there] had changed,” he said.

“In the Birmal sub-district, for example, I’ve been told I am not to set foot there,” he added.

Wazir said despite the Taliban defeat, strong conservative values amongst the people of the area still mean that musicians are looked down upon, and performances are difficult to arrange.

South Waziristan Agency to have cricket academy

Last year, the head of a local government-backed peace committee distributed pamphlets banning all musical and dance performances in South Waziristan. The government denies that such a ban was ever actually imposed, but locals say the event created an atmosphere of fear.

Natives of South Waziristan say that where the Taliban enforced a complete ban, similar restrictions are now socially enforced.

“Under the Taliban rule, it was banned outright, you could not perform at all,” said Mansur Khan Mehsud, the Islamabad-based director at the FATA Research Centre. “But there are also conservative values there, so most people do not consider it a good thing to do. It is considered an insult to call someone a musician.”

Rehman also spoke about the immense social pressure for him to stop making music.

“In all Pashtun society, and particularly in Waziristan, singing and music is always enjoyed, but for some reason when the singer is from their own area or family, people look down upon that.”

Unlikely heroes

However, there are people willing to risk their standing in the society to help support the budding music industry in the area.

One of the unlikely heroes of this scene sits in a small, cramped mobile phone shop in the Tank Adda area of Dera Ismail Khan.

Waheed Nadan, 22, is the owner of the ‘Aman Mobile Zone’, and musicians across the region have lauded his efforts to connect often technologically illiterate musicians with their audiences, by uploading their music onto users’ phones, as well as to social media sites like Facebook and YouTube.

Fading out: Ganr Khat – whirling relic of Waziristan’s culture

“Aman Mobile Zone has done a huge service for musicians from South Waziristan,” said Wazir. “I would say that we have sung songs for South Waziristan, but he has been the one to take it to the people.”

Nadan's Facebook music page now boasts almost 30,000 followers, and he has uploaded more than 80 music videos to YouTube, where he also has a large following. He monetises his videos through advertisements to earn a modest income off his work.

“My faith is that I have to keep the sadness of the world upon myself. […] Right now it is not the time to earn, it is the time to help people,” said Wazir.

“I have a poem: ‘If someone wants there to be silence, then they must either cut my tongue, or cut off their own ears’.”

This article originally appeared on Al Jazeera.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ