Beyond female voters’ registration

About 12 million women are missing from the electoral rolls in the country

The writer is chairperson of Free and Fair Election Network and heads Pattan Development Organisation. He may be reached at bari@pattan.org

The newborn males slightly outnumber newborn females. This appears to be a universal truth. Besides nature’s doing men perpetually remain at a higher risk of dying in its own realm than women as they inflict death upon them by waging wars and violence, causing accidents and disasters, etc. This ‘equalises’ the sex ratio in most countries. The population experts argue that in case sex equilibrium is skewed in a country, it means some kind of discrimination against females is being practised. Pakistan is one such country.

And this manifests in the country in almost all spheres of life — from literacy to share in inheritance, from employment to legislation, and above all from counting too. Just consider this. Only 4% women were deployed as enumerators for the conduct of the sixth population census. No wonder contrary to common perception, we have more males than females — 51.3% males and 48.7% females. Meaning there are 105 men for 100 women, which is almost equal to Asia’s average. This is the worst sex ratio in the world. Africa has better.

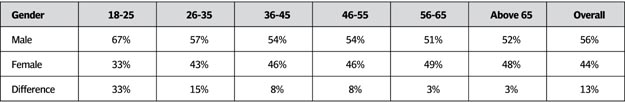

Scandalously, the sex ratio amplifies on the Pakistan’s latest electoral rolls. I will call it Electorate Gender Gap. It is as large as 12.6% (12.17 million). Even after adjusting with the census sex ratio, it remains as big as 10%. Of the total 97.02 million registered voters, 56.3% are males and 43.7% females. Making boring statistics simple is must. In 1970 and 2002, we had 87 and 86 female voters to 100 male voters respectively. In 2013, it had dropped to a historical low — 77 to 100. Currently it stands at 78. Over the decades, instead of improving registration of our women, we spread their disenfranchisement.

On many accounts, including registration of women as voters, we lag behind our neighbouring countries. In 2015, Bangladesh had 51% male and 49% female voters — had a tiny gap of 2% (or 2.11 million). India too has fewer women than men on rolls. But has small gap. Some states of India (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Pondicherry) have more females than males, while some Indian states nearer to us, ie, Punjab, the union territory of Chandigarh, and Haryana have fewer female voters than males.

In all regions of Pakistan we find skewed sex ratio on the rolls in favour of males. Amazingly Lahore and Faisalabad are in the lead. Are there any socio-cultural similarities that are keeping millions of women across the border out of the rolls in their respective countries? As far as restrictions on women’s mobility and segregation between the sexes are concerned both countries look alike if not entirely same. Gender-based discrimination and violence is a major factor for having fewer women on the rolls. These restrictions are intensely applied on female youth in rural areas than the urban centres. Women have to get prior permission to see a doctor even if the doctor’s clinic is around the corner. A woman particularly a young one would not dare to think to go to NADRA Registration Centre (NRC) for CNIC registration which is now mandatory for vote registration.

The following table (based on ECP data) clearly establishes this fact — the younger the female, the lower the chance to be on the roll as they suffer from most intense restrictions on their mobility.

Like Pakistan, India too is struggling to register young female voters. For instance, India’s Haryana is like our Fata as both have less than 30% young female voters. Similarly, Both Pakistan’s and Indian Punjab have huge gap between young male of female voters. Set aside India.

Though NADRA has established 517 registration centres and 159 Mobile Registration Vehicles (MRVs), amazingly only 51 of them were reserved for females. However, during the month of December more MRVs have been allocated for female registration. There are serious public policy issues at play too. First, opportunity cost for women to take a day off is too high, while she sees no benefit in getting a CNIC. And if she asks someone from the family to accompany her, the opportunity cost multiplies. Second, a person who is applying for CNIC the first-time must bring a blood relation to the NRC, which is not possible for a woman whose parents and siblings may live in a far-flung area. It’s a fact of women’s life — all of them leave their parents’ home after getting married. Would someone come from her family just for CNIC registration? Of course not, calculate its opportunity cost too. Third, NADRA is bound under the policy to charge no fee from first time female applicant. However, it has been reported to us from many places that NRC officials forced women to apply for smart CNIC which costs Rs1,600. And if a female applicant has a B Form, she is forced to pay Rs400. Correct it please.

Moreover, politicisation of MRVs must be highlighted. Not all but most of the ruling party parliamentarians reportedly control mobility and placing of MRVs. Instead of providing service where under-registration exists, MRVs are used to register people who would be their voters. Also, it has surfaced that MRVs serve more men than women in many places. These corrupt and partisan practices undermine efforts of the ECP, donors and the civil society organisations, and above all of NADRA’s too. Result, the gender gap not only persists — it has also increased from 10.97 million in 2013 to 12.17 million in 2017.

In order to fill this void, the Free and Fair Election Network with whom I am associated has been working with communities where unregistered women are in large numbers. We are enlisting unregistered women, assisting them to apply for CNIC, and working closely with NADRA and the ECP. So far we have facilitated about a half million persons, while our target is to reach out to 1.7 million unregistered women. In most areas, NADRA and ECP officials are cooperative but policy bottlenecks need to be removed immediately. But we must also look beyond mere registration gap. The underlying factors must also be addressed. Otherwise we will be repeating the same campaign over and over again every December.

Published in The Express Tribune, December 9th, 2017.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ