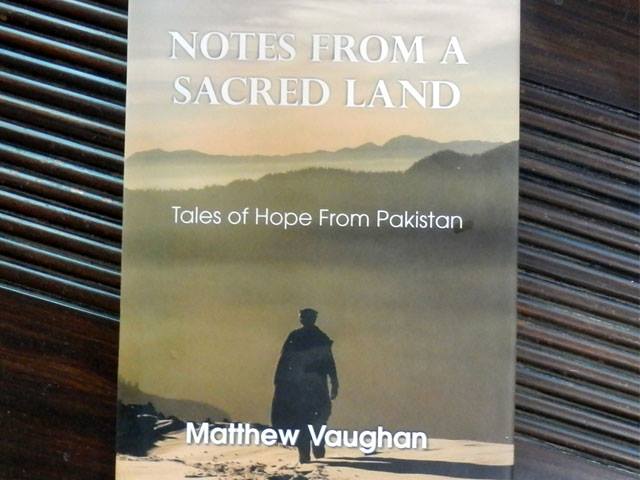

Scathing critiques often by local authors will unfold a litany of woe, a wash of victim-hood and deception. War and hunger and poverty and failed development programmes. To be sure there are exceptions but they are few and far between, and that is where Mathew Vaughan has with a single title invented a whole new genre – Positive Pakistan.

Ahsan Khan is writing a book that will surely leave you teary-eyed

This slender tome – a fast reader will finish it in an evening – consists of 20 loosely connected anecdotes about the life and times of a gora, Urdu speaking, that has lived in Pakistan with his wife and children since 2011. The picture his words paint is instantly recognisable to any foreigner that lives ‘in the wild’ – out in the community rather than in a gated compound. This is life at the nuts and bolts end, the end where taxi drivers can either be of saintly virtue or the bane of one’s life.

There are passages of dialogue – ‘Murree cricket match’ being one – that are very Pakistani and at the same time very English, the two coming together neatly and sewn together by leather and willow. The pages almost smell of cut grass, tea and cucumber sandwiches.

Alongside that is an altogether darker piece on a visit to an orphanage in Faisalabad. The orphanage itself is a spark of light in the midst of appalling poverty, and the author catches the squalor, the filth, with an economy of words that say just enough. The description of a visit to the home of one of the children who lives in the orphanage is achingly poignant, and towards the end Vaughan says…’The aunts look at me quietly and I realise that I have nothing to say to them, as though communicating across the chasm of poverty will require me to speak in a language with which I am not familiar. I feel like an alien, dropped into a separate world…’ It is that sense of separateness, of being the outsider looking in but with an eye far sharper than a casual visitor or tourist, that infuses the entire book.

Roald Dahl's new personalised book makes you a character in Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory

There is also a sense that although Pakistan can be infuriatingly obtuse and downright awkward for us foreigners to live in it is also warm – in the human sense – welcoming and as I have discovered myself over the years, very bad for the waistline.

Pakistan tends to generate its own bad press, and the literature generated by Pakistan in the last three decades at least feeds a circular argument, a snake eating its own tail. Breaking that roundabout of grim headlines was never going to be easy but Matthew Vaughan takes us out of the rut, gives a nod and a wry smile and leads us down a different path entirely – and Pakistan is all the better for him doing so. Recommended.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

1722586547-0/Untitled-design-(73)1722586547-0-165x106.webp)

1732326457-0/prime-(1)1732326457-0-165x106.webp)

1732308855-0/17-Lede-(Image)1732308855-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ