While cities or urban centres are rightly called the "engines of growth", they can only prove to be so if the influx does not outstrip planning. No marks for guessing how things are in Pakistan. The lack of allocation for developing many urban centres has meant that population concentration has taken place in bigger cities like Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad, Hyderabad etc. Karachi right now is one of the most rapidly urbanised cities in South Asia.

The price Karachi pays for its inefficient public transport system

Madness on roads

How are the needs of this burgeoning population being met? Well, that is the question Pakistan has been struggling to answer. Unfortunately, from the array of available solutions, seems to have settled for the infrastructure solution rather than a holisticly planned one that could be cost effective with long-term sustainability.

One of the many bridges in Karachi. PHOTO: Online

One of the many bridges in Karachi. PHOTO: OnlineThis is why while a bird’s eye view may present a vista of a futuristic landscape with highways, overheads, flyovers, underpasses, and undulating steel and glass structures of Metro lines and stations, the situation on the ground is nothing but a traffic tangle.

This madness on our roads ruins the air quality through prolonged fuel emissions at bottlenecks. The every-hungry transport sector results in high cost of fuel imports. And then there is a huge environmental cost of these infrastructures cost that cause human displacement and habitat loss, through stripping of the already meagre tree cover.

We have seen that happening in Lahore, through its Metro and now the Orange Line. Also, in Islamabad, which is not a dense urban centre by any stretch of the imagination, yet hogged the resources because of being the capital city, and now Karachi whose green cover is being stripped for the Green Line.

Are Pakistani cities prepared to handle new traffic CPEC will bring?

What can be done?

Make no mistake; we need public transportation solutions that are long term and take into account the growth projections of the cities. However, the cost-benefit analysis needs to take into account not only the factor of how many people will benefit from the (artificially) cheap fares, and what impact that has on the economy. It is extremely important to consider this because none of the projects are the result of the largess of any of the brotherly Islamic or non-Islamic countries; they are all being built through loans that have to be repaid.

Lahore Metro Bus Project. PHOTO: Online

Lahore Metro Bus Project. PHOTO: OnlineWhen calculating the benefits, one must look at what percentage of the city’s population benefits from these measures. Is a hub and spoke system in place that facilitates people from beyond the immediate vicinity? And, which demographic is still totally marginalised? What about the very young, children, or very old or the disabled? Or the pedestrians whose rights are violated through the obstructions, or small businesses, for instances pushcart vendors, etc.

Another problem is that where public transport is unavailable, the road and highway network, underpasses and flyovers and signal-free corridors built to shave off maybe half an hour of drive time of the rich and affluent serve as a barrier to mobility of those who cannot afford vehicles. So billions spent on their construction actually cannot be justified, as none of these developments are pro-poor.

Collect data before you start anti-pollution project

They are also myopic. While a lot of song and dance is being made about putting in place modern public transportation systems, licenses are being given in thousands daily to private cars and motorcycles. This means that while the wide roads and flyovers invite and even encourage people to invest in private vehicles, after about five years, we are standing at the same stage of traffic congestion we were at when they were planning to remove the bottlenecks!

What is being done?

So, do we build more bridges and highways? No! We need those infrastructure projects to correspond to a sustainable urban transport system that has multiple solutions like buses on dedicated bus lanes, elevated light rail, and underground trains. Moreover, please let us not hear the reluctance forwarded that it cannot be done in congested cities like Karachi, Lahore, etc. because things do not really get more congested than they are in Kolkata, and they built an underground train system.

Kolkota monorail. PHOTO COURTESY: Subways.net

Kolkota monorail. PHOTO COURTESY: Subways.netNew Delhi too has its Metro that services a larger slice of its population than does the one built in Lahore and Rawalpindi or Islamabad. Most of the cities across Europe that have them are also old cities.

In fact, let us look around and see the different solutions that can be implemented.

Tiny Singapore has an immaculate public transportation system. So does Hong Kong. Buses, underground and overland trains, even ferry services and boats or river taxis to use the waterways. The per capita income is quite high. People of corresponding incomes in Pakistan can afford luxury cars, for more than one member of the family.

CDWP clears way for Karachi Circular Railway, Peshawar Sustainable Bus project

Nevertheless, not many people own their own vehicles there as they are expensive. The tax structure makes them so. Then the fuel prices are also kept high… not subsidised. This is also a huge discouragement. Parking spaces and fees are other discouragements. Still, the government does not just wield the stick. It offers the carrot of efficient transport system on the infrastructure that can justify the cost through its usage.

From Penalosa with love

Now the environment too is a great consideration. Singapore has had the odd and even number plate system of cars allowed on the roads for a long while. Therefore, at any given time only half the cars can be on the road, which ensures emission reduction. When the Indian capital was beset with smog and fog in 2016 due to exhaust emissions that made many days, zero visibility days, this was the solution they caught on to and it delivered the desired results.

In Pakistan too, environmental organisations have been working with the government to draw similar plans through programmes such as Pakstran. They have been urging for mass transit systems in the context of emissions control. This is especially significant in the context of climate change and Pakistan’s commitments to reduce emissions.

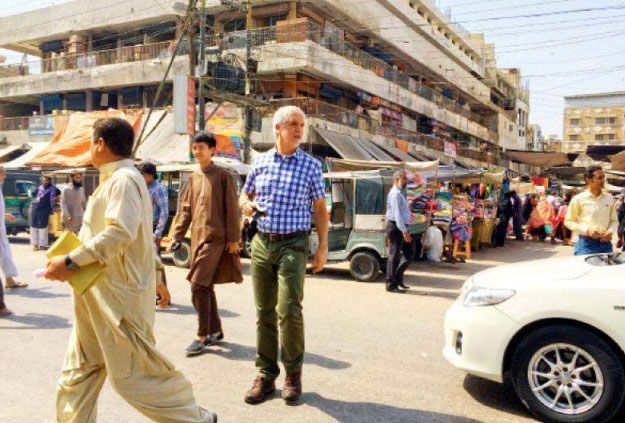

Enrique Penalosa walks along MA Jinnah Road, Karachi. PHOTO: Express

Enrique Penalosa walks along MA Jinnah Road, Karachi. PHOTO: ExpressBy far, the most successful models of dealing with urban transportation woes come from far off South America. It is impossible not to cite the example of the miracle worker Enrique Penalosa, the former mayor of Bogota in Colombia when talking about urban transportation. His is a success story that is mindboggling.

He tackled a very complex problem and sought a solution that seems simplistic in nature. Nonetheless must have taken some doing in a city wracked by crime and gang warfare, not unlike our very own Karachi. By designating pedestrian zones and bike lanes, he changed the entire complexion of his city and brought about a kind of social engineering that turned Bogota into a vibrant, healthy, secure, and inclusive city from a crime and congestion-ridden one.

From Bogota with love: Karachi gets advice from Colombia

The sad irony is that he was invited to Pakistan in 2005 to advise on these issues, yet nowhere can we see even a shadow of what he had advised.

Similarly, Curitiba in Brazil also presents a model of sustainable urban transportation which overlays the Bus Rapid Transit System with green spaces and urban housing for the poor instead of displacing and dispatching them to the least-favoured parts of the city, as we have seen in Pakistan with the widening of road networks and bridges.

The world is dotted with many examples that can be studied, modified and implemented to bring about the least disruptive, cost-effective and sustainable transportation system that does not rely just on some grand exercise in optics and actually helps propel the urban centres as engines of growth instead of quagmires of traffic jams because of confused policies.

Karachi on a busy day. PHOTO: AFP

Karachi on a busy day. PHOTO: AFPKarachi’s plea

Many international agencies have been calling for the overhaul of the system and been willing to offer assistance. A classic case in this connection is of the Karachi Circular Railway, which was discontinued due to economic unviability. The Japanese, through Japan International Cooperation Agency, has shown willingness to finance its revival on several occasions. Dragging of the feet by successive governments meant that there were cost escalations many times over.

Now, finally, since the project has been tagged with China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the approval has come through, so hopefully, it will serve as, at least, one more piece that will fit in the gigantic jigsaw of Karachi’s traffic needs.

The decision of the World Bank (WB) to step in with the intent of ‘transforming Karachi into a world class, inclusive and sustainable city,’ is also an attempt to make a holistic attempt at making it a sustainable urban centre. Transportation solutions will be a key in this planning. They are also needed for other urban hubs of the country, along with the provision of access to services and utilities to people on their peripheries, if they are to deliver on the promise of growth attached to them.

The abdication of responsibility of the public sector gave space to the mushroom, the unmanaged and unscrupulous growth of the transport sector, in the country's commercial hub, and it assumed a political life of its own. There was another downside to the growth of the road transport sector, and that was the decline of the railways as haulier and carrier of goods, which also took to the roads. The decline in this significant source of revenue had a direct impact on the quality of its service as a passenger carrier, and it is only of late that it has come out of its existential crisis.

Afia Salam is Pakistan's first female cricket journalist. She now writes freelance on the environment, climate change, gender issues, and media ethics. She blogs at afiasalam.wordpress.com.

1719660634-1/BeFunky-collage-nicole-(1)1719660634-1-165x106.webp)

1724249382-0/Untitled-(640-x-480-px)1724249382-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS (6)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ