India’s Dr No: ‘We can’t pollute our way to success’

The maverick environment minister who likes to annoy.

India’s Dr No: ‘We can’t pollute our way to success’

India’s maverick environment minister Jairam Ramesh is more than a little smug that at one time or another he has raised the hackles of big business, cabinet colleagues and environmentalists.

“It must mean I’m doing my job,” grins the 56-year-old ex-policy adviser turned politician who is now one of the ruling Congress party’s highest-profile ministers with close ties to the Gandhis, India’s leading political family.

Since taking over the role in 2009, he has given a tough new image to the ministry, which had been seen as a rubber stamp for industrial projects, and has also raised India’s profile on the world stage in fighting climate change.

“India didn’t cause the global warming problem but we definitely want to be seen as part of the solution,” says Ramesh, whose nimble diplomacy helped broker a global climate deal at Cancun, Mexico, last December.

Even before he took over the portfolio, the affable, media-savvy Ramesh was well-known in India as an author and columnist.

Typically, he was again enjoying the limelight last week when he announced a rise in India’s population of wild tigers, an upbeat message delivered with a warning that development was shrinking the endangered animals’ habitat.

Ramesh’s latest big move — after reportedly being prodded by Congress party colleagues to be more conciliatory to business — was his approval of plans by South Korea’s Posco to build a $12 billion steel mill earlier this year.

But Ramesh, an engineering graduate of the elite Indian Institute of Technology who also studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, attached over two dozen riders to his approval.

“The bulk of projects still get cleared,” he said in a recent free-wheeling interaction with foreign journalists. “It’s just there are more falling into the ‘Yes, but’ category to which I attach conditions.

“But there are also times I have to put down my foot.”

He has shelved plans by British giant resources Vedanta to mine bauxite on land held sacred by tribal people, ordered demolition of a ritzy Mumbai condominium that violated shoreline protection rules, and stalled construction of a luxury town in western India.

Worries have been raised in government and financial circles that Ramesh’s zealous enforcement of environmental rules is creating regulatory uncertainty that discourages foreign investors and blocks industrial development.

“There is a question of consistency of policy in India that worries foreign investors,” said Deepak Lalwani, head of London-based Indian investment consultancy Lalcap.

Ramesh replies there is “no empirical evidence” to suggest his vetoing of projects has contributed to a sharp drop in foreign investment or that his pro-green stance is a barrier to growth.

But the minister, who favours traditional long white shirts and trousers, says he believes “the time has come for India to make tough choices.”

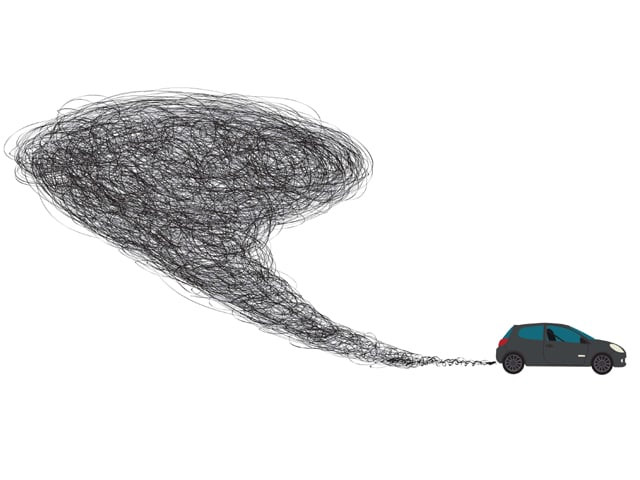

While being an early advocate of opening up India’s still relatively closed economy, he is adamant that “India cannot pollute its way to prosperity.” The country must ensure its growth — expected to reach nine percent this year — is ecologically sustainable, he says.

Since the Japanese nuclear crisis began, he has said energy-hungry India “may have to pause a little” in its ambitious plans to massively expand nuclear power “to look at our state of preparedness for emergencies”.

He has been accused of being dogmatic by cabinet colleagues and too pliant by some environmental critics. But he has admirers.

Medha Patkar, founder of Narmada Bachao Andolan group which lobbies to halt construction of river dams, supports Ramesh’s record.

“He doesn’t mind taking a position when he’s convinced of what is legal and what it is that the ministry should uphold,” says Patkar, praising his “down-to-earth” and “pro-people” approach.

But Ramesh says he has to be realistic about what he can accomplish because of India’s limited resources.

He says he is attaching more conditions to some environmental approvals but many are “leaps of faith” because India lacks the administrative network to police their enforcement.

He hopes public awareness will put more pressure on companies, helping the government’s efforts to find the right balance between growth and environmental concerns.

“I’ve never said I’m here to reject projects,” he says. Referring to his media nickname, he adds: “I’m not Dr. No.”

Published in The Express Tribune, April 4th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ