Kashmiris master the ‘art’ of resisting Indian rule

With changing dynamics, creative resistance becoming part of larger political movement for right to self-determination

Kashmiris master the ‘art’ of resisting Indian rule

Born in 1993, when the uprising was at its peak, 23-year-old Khytul Abyad uses her brush to depict life amidst violence. A veranda in her home, in the south of Indian-administered Kashmir, turned into an old-styled glass room is well organised. A wooden easel rests in the corner; a knee high table beside the easel is divided into three segments. The right side of the table is occupied by different paint brushes in a pen-holder, a set of crayons in a tray and few colours; some paintings and white sheets in the centre; and novels at the other end.

‘What’s happening in Kashmir is not a revolt but a revolution’

Despite her young age, she has witnessed violence up close. Her father, Mirwaiz Qazi Nissar, a renowned Muslim cleric and pro-freedom leader, was assassinated by unidentified gunmen when she was just 18-month-old. And she soon got familiar with words like aazadi, army, killings, curfew and torture. As time passed, Abyad began to observe life in Kashmir and came to believe that the meaning of “normal life” in Kashmir changed because due to the “absence of peace”.

A sketch by Khytul Abyad.

A sketch by Khytul Abyad.After Indian forces killed Burhan Muzaffar Wani, a young commander of pro-Pakistan rebel outfit Hizbul Mujahedeen, in July last year, hundreds of thousands of Kashmiris filled the streets in protest. Violent anti-India demonstrations erupted in south Kashmir and spread to all ten districts of the Valley within hours. The local state police, Central Reserve Police Force, and the army used live ammunition to contain the bulging crowds. But the protests didn’t subside and civilian killings continued at regular intervals. More than 90 people were killed and over 17,000 were injured by pellet guns, tear gas shells, and assault rifles.

The region was forcefully shut for two months by imposing a back-breaking curfew, particularly in south Kashmir.

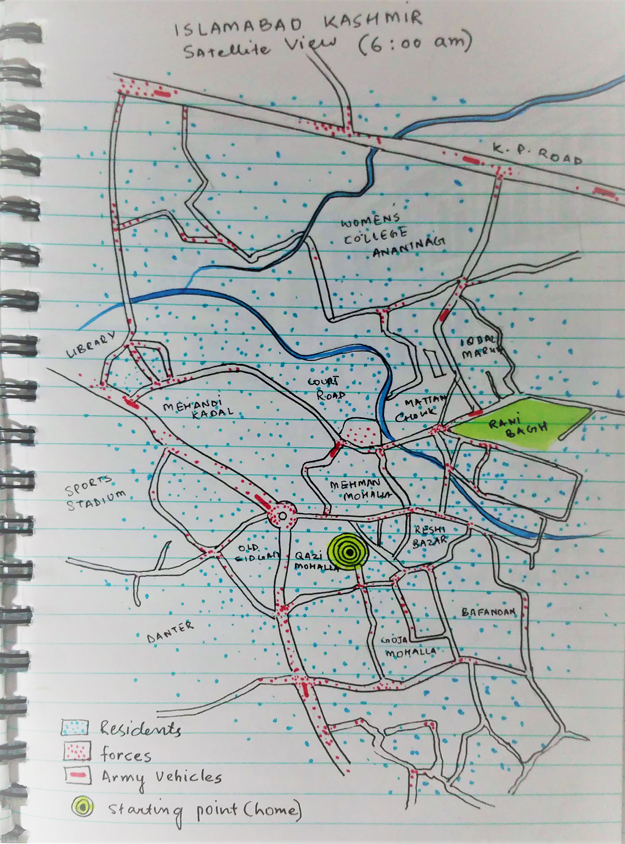

A map drawn by Khytul Abyad in her notebook.

A map drawn by Khytul Abyad in her notebook.Abyad, an ardent art lover from her school days, decided to give vent to her rage from all the mayhem in her hometown of Anantnag through paintings. When people, mostly youth, were busy throwing stones at Indian forces, her passion became an outlet to express her anger and portray what she says was the “reality” of Kashmir.

“Everyone cannot come out on streets and throw stones. This restlessness lit a spark inside me. When I could not do anything about the frustration brought in by the chaos outside, painting was my only way to vent,” Abyad says.

Her paintings and visual stories, she describes, reflect her version of “normal life” in Kashmir – which is abnormal by every standard.

The Deconstruction, a portrait of a young Muslim girl, represents Kashmir for this young artist, who is presently pursuing her masters in art and design from Beaconhouse National University in Pakistan. Half of the face looks beautiful, while the other half looks disturbed. “That's how this place [Kashmir] is like. You visit Kashmir, you see its beauty, but you don’t know what is going inside it and what is going to happen next moment,” she explains.

A sketch by Khytul Abyad.

A sketch by Khytul Abyad.The other painting, a landscape of her Neighbourhood, is an outcome of her childhood memory. “A few kilometres from here is an army bunker on a hill which would scare me when I was a child. The place I live in was very congested. As a child, I used to believe people had adopted themselves in that congestion to save themselves from the danger of the bunker, just like animals adapt themselves with respect to the environment they live in. The camouflage I made is in reaction to that memory of a child,” she continues.

Abyad believes that Kashmir doesn’t have its own voice and art being immortal reaches more masses because it breaks barriers of language, nationality, religion and gender. She was among a few students of Music and Fine Arts department at the University of Kashmir who used a broken chinar tree as a canvas to express their emotions.

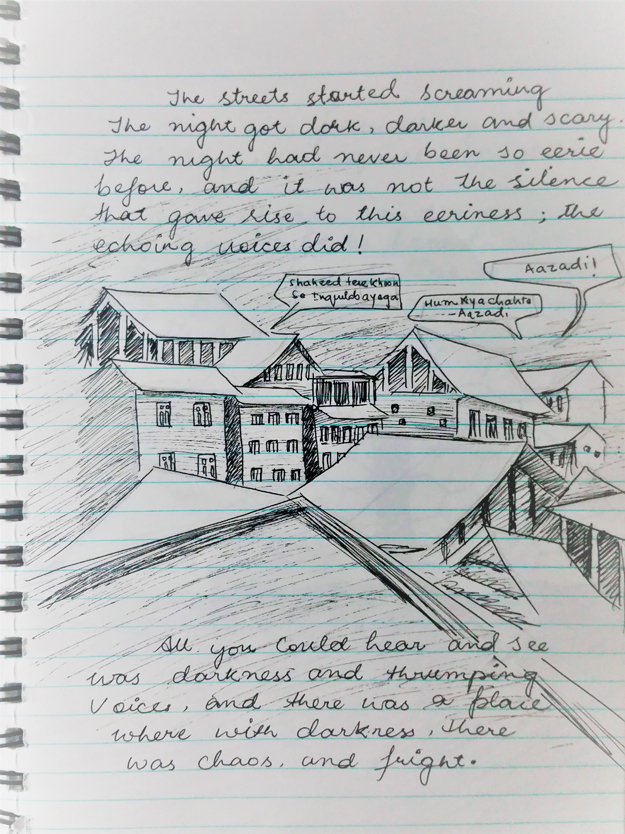

A page from Khytul Abyad's diary.

A page from Khytul Abyad's diary.If Abyad uses paper canvas, others used nature for their expressions. Earlier in January, when Kashmir witnessed heavy snowfall after many years, social media was abuzz with ‘snow art’. Many professional artists and amateurs took it as an opportunity to express their anguish against the government’s crushing of the summer unrest. Some people made snowmen depicting Pakistani soldiers, rebels and pellet victims while others made pro-Kashmir and pro-Burhan graffiti.

Art as a new language of resistance started to emerge in Kashmir after the 2008 unrest. The Government of India and state government of Jammu and Kashmir had reached an agreement to transfer 99 acres of land to Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board in Pahalgam, to erect concrete structures for the Hindu pilgrims who visit Kashmir every year. People in the Valley opposed the decision by coming out on the streets and staging anti-India protests. In reaction, 65 unarmed protesters, mostly teenagers, were killed by the security forces.

India uses excessive repression in occupied Kashmir, reports Amnesty

During the 90's, when rebellious activities were at its peak, Kashmiri people believed that the gun was the only option left and but today, nearly three decades later, youth is seeing art as another option for the same cause. Many young people have emerged either as writers, poets, painters, rappers and graffiti artists.

The 2016 turmoil is also known as the year of mass blinding. At least a thousand of young boys and girls suffered serious eye injuries after being shot by pellet guns. For every shot fired by the Indian forces, 300 to 600 tiny little iron balls would spread indiscriminately into the air. As a result, more than one hundred people, including children, were permanently blinded either in one eye or both.

Gowhar Nabi Gora, a 42-year-old veterinary doctor and a pebble artist, could not resist after witnessing such sufferings. To express solidarity with the pellet victims, he gave life to pebbles. “Different people have different ways of telling their stories, using stone and turning them into art pieces is my way,” he says.

Veterinary doctor and pebble artist Gowhar Nabi Gora. YOUTUBE SCREENGRAB

Veterinary doctor and pebble artist Gowhar Nabi Gora. YOUTUBE SCREENGRABTo show the plight of youth blinded by pellets in previous summer, he collected different types of stones and assembled them in different ways to make his depiction. “The sufferings of the people inspirited me to depict their sentiments through my art,” Gora says.

The veterinarian is fond of collecting stones and pebbles since childhood and even carries stones to his office. One finds his recent work laying on a table in his living room.

A round stone is painted red and it looks like an eye is popping out of an eye socket. He has named the stone ‘2016’. Gora believes by carving scars of the pellet on stones one can reflect the pain and loss of vision. “This stone depicts a mutilated eye. This is what happened last year. People in large number were blinded and through this art, I tried to shed some light on the pain of those victims,” Gora says.

Stones depicting mutilated eyes of Kashmiri protesters. YOUTUBE SCREENGRAB

Stones depicting mutilated eyes of Kashmiri protesters. YOUTUBE SCREENGRABThe stone artist says the pebble used for ‘2016’ was a gift from God as it naturally had the contours of a human eye. “I just had to paint it; the rest was already there,” he shares.

Kept near the ‘2016’ artwork is another brilliant stone art - Gora has assembled different stones in a way that they look like a mother holding her child in a lap. He has dedicated this artwork to a 14-year-old pellet victim, Insha Mushtaq, who was watching a protest from the window of her house when a policeman fired pellets at her. “She has become a symbol of pain. As an artist, I try to convey a message that life in Kashmir is different from the rest of the world,” he stresses.

Artwork dedicated to 14-year-old pellet victim Insha Mushtaq. YOUTUBE SCREENGRAB

Artwork dedicated to 14-year-old pellet victim Insha Mushtaq. YOUTUBE SCREENGRABIf visual artists have had their say, musicians have not lagged behind. A 23-year old singer and a student of business administration, Aamir Ame – known by stage name – Emcee Ame, started his rapping career in 2009 with an album, ‘Dedication’. His songs were poetic and romantic ballads and depicted love and peace. But last summer changed the course of his music and the romantic rapper turned into a political one. “I had never read about politics neither was I interested in it but I had to express my emotions after witnessing the bloodiest summer of my life. It is painful to see your own people becoming handicapped,” he shares.

Earlier this year, Ame dedicated ‘Dead Eyes’ – an anti-India rap about pellet victims - on the occasion of India’s 68th Republic Day. The song blends Kashmiri and English languages and speaks of stone throwers and incarcerated youth. The lyrics also question India’s role in Kashmir, its judiciary, and the role of the United Nations in the entire matter.

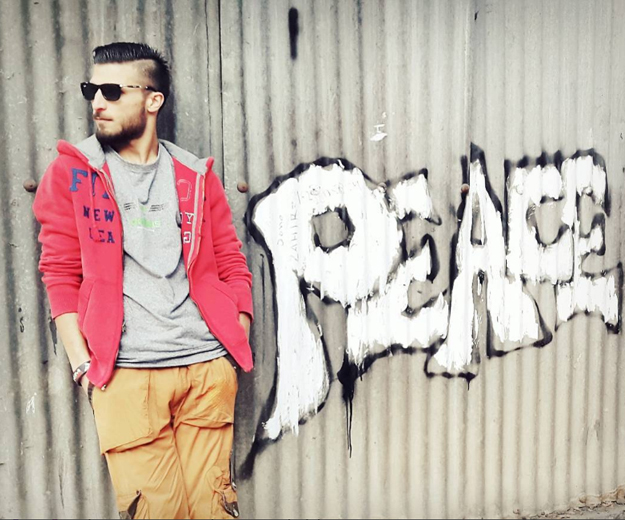

Singer and student of business administration Aamir Ame. PHOTO: FACEBOOK PROFILE

Singer and student of business administration Aamir Ame. PHOTO: FACEBOOK PROFILEThe song turned out to be a big hit in Kashmir and other parts of the world – so much so that it caught the attention of Shady Joe, a Nigerian rapper and a vocalist from Nagaland.

Ame and three other members of his band then dedicated the song “We Gonna Rise Kashmir” to the women of Kunan-Poshpora, a remote village in the district of Kupwara in north Kashmir, who were allegedly raped by Indian Army in the spring of 1991. Indian troops had launched a search operation in the village and allegedly gang-raped around 35 women. Human Rights Watch has reported that the number of raped women could be as high as one hundred; however, the Indian government claims these allegations are baseless.

Warning: the video below contains graphic images

Gowher Geelani a senior journalist and political analyst, says creative resistance has diversified the Kashmir narrative. He says that once 2008 elections were held, there was a conscious transition from violence to non-violence. “People came out on the roads in big numbers and then people started writing,” he says.

Sexual warfare in Indian Kashmir

“We now have a good conflict literature be it from Mirza Waheed’s Collaborator or Basharat Peer’s Curfew Nights. People are fighting on multiple levels, so creative resistance is a part of the larger resistance,” Geelani further explains.

The journalist also believes creative protest would definitely invite more global attention which will eventually benefit the political movement for the right to self-determination in the longer run. Though he admits it will not have immediate results.

Rapper Ame considers art as one of the best ways to make people, living in different parts of the word, aware of the tormenting situation in Kashmir. After he sang a few conflict-oriented songs, some non-governmental organisations approached him to help pellet victims who lost their eyesight. “Though I refused their offer of financing me for certain reasons, I want to say that art has the power that no one can underestimate. I was a stranger to Joe but through the art of singing, he came to know about me. He contacted me and asked if he can contribute for Kashmir cause without charging a single penny,” Ame shares.

Ame's song ‘Dead Eyes' talks about stone throwers and incarcerated youth of Kashmir. PHOTO: FACEBOOK PROFILE

Ame's song ‘Dead Eyes' talks about stone throwers and incarcerated youth of Kashmir. PHOTO: FACEBOOK PROFILEMuheetul Islam and Insha Farhat are freelance journalists from Indian-administrated Kashmir with master’s degrees in journalism from Central University of Kashmir.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ