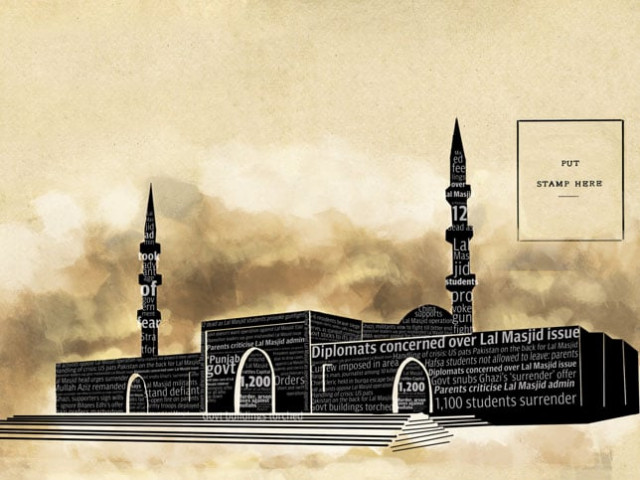

Lal Masjid: Rebuilding the legacy

Four years later, the impact of Lal Masjid’s siege keeps resonating through Pakistan.

“I’ve become fearless,” Aba’a* says, when asked about the impact of Operation Silence on her life. “When people are scared before crossing a street, I tell them death is not written here.”

The 25-year-old taught Arabic grammar and Quranic tafseer at Jamia Hafsa. Along with several students and teachers, she was inside the madrassa during the July 2007 operation.

Almost four years later, she says the events have “become part of my identity”.

Legacy ‘hijacked’

Lal Masjid has become a part of Pakistan’s identity as well. The impact of the operation became evident in a number of ways. Suicide bombings, not a new phenomenon to Pakistan, multiplied in 2007. The operation provided militant groups with a reason to attack the state and a string of suicide bombings targeting the army, police and citizens took place throughout the country. A few weeks after Operation Silence, 200 Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan fighters occupied Haji Sahib Turangzai’s shrine in Lakaro, Mohmand Agency and renamed it after Lal Masjid.

One of the groups that formed after the siege was the Ghazi Force, named after Lal Masjid’s Maulana Abdul Rasheed Ghazi, who was killed in the operation. It is reportedly led by a former student of Lal Masjid. The Associated Press reported last year that Ghazi Force was behind several attacks against security forces and a suicide bombing at the World Food Programme office.

A student of Jamia Faridia (which is run by Maulana Abdul Aziz), who was reportedly a commander of the Ghazi Force, was arrested outside Aziz’s house in 2009.

Aziz denies any involvement with such groups. “This is not in our hands,” he told The Express Tribune. “These were young people from the tribal areas and they formed organisations using the name of Lal Masjid.”

Instead, he says, people are disappointed. “They are upset at us!” he exclaimed. “They ask if we have done a deal with the government and ask us to rise up.”

Aziz appears to condone their acts when he says, “where there is oppression and injustice, there will be a reaction.”

He blames the government for sealing madrassas during the siege. “We had told them that we will lose control over the students,” he says. “They did not listen.”

Making headlines

Since 2007, Lal Masjid’s name has popped up repeatedly. According to the New York Times, Faisal Shahzad, the would-be suicide bomber who targeted New York’s Times Square, was connected to the mosque and had met with the 17-year-old nephew of a Pakistani Taliban leader there.

Its naib khateeb says he is unaware of any connection Shahzad had with Lal Masjid.

Lal Masjid made headlines again last year when former Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) officer Khalid Khawaja was kidnapped and killed in North Waziristan. In a ‘confession’ video, Khawaja spoke of his regret over the siege, and said he had worked with the ISI, the Central Intelligence Agency and religious and political leaders to implicate Lal Masjid. Khawaja ‘confessed’ to telling Aziz to escape the mosque in a burqa, and claimed his wife had egged on Umme Hassan.

This was denied by Khawaja’s family, who said Aziz’s family had stayed with them for a month. Khawaja’s funeral prayers were offered at Lal Masjid.

The political casualty of the Lal Masjid saga was the then-president Pervez Musharraf. After Operation Silence, public opinion turned against Musharraf, who was already dealing with the judicial crisis.

While Musharraf says he has no regrets over the operation, the sentiment that drove the students of Lal Masjid and Jamia Hafsa to challenge the state is still prevalent.

Fearless, remorseless

Before the siege, Jamia Hafsa’s students illegally occupied a library and became self-styled moral guardians by ‘kidnapping’ women they suspected of immorality.

“My relatives told me to leave,” says Bint Fareed, who also taught at Jamia Hafsa. “So did Maulana Abdul Aziz and Umme Hassan. I was not scared inside the madrassa, even though we could hear the shells and bullets outside. I was scared when we left with the injured girls.”

She describes feeling disoriented as she exited the madrassa. “Even though we had been outside so many times before, I could not tell where we were or where we were going. I had no idea what state of curfew had been imposed or how many roadblocks there were. We somehow managed to find our way into the city.”

It never occurred to her to pack her belongings. In a wistful tone, she muses, “I never realised that it would be the last time we would see our home.”

When asked if she would repeat any of the actions that led to Jamia Hafsa’s notoriety, Aba’a replied, “I would do the same again. We will do whatever we can.”

Lal Masjid’s naib khateeb Maulana Amir Siddiq says he encourages students to excel in their fields and contribute to Pakistan.

“However,” Siddiq said, “What message is the empty ground where Jamia Hafsa once stood giving to emotional young people?”

*Not her real name

Published in The Express Tribune, March 14th, 2011.

1724319076-0/Untitled-design-(5)1724319076-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ