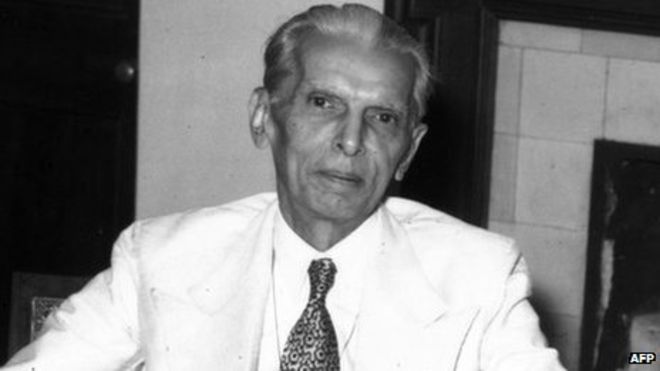

No one — perhaps least of all the Quaid-e-Azam himself — could have foreseen in 1947 how this country would lurch away from the enlightened ideals of its first leader and into the arms of obscurantists. As we — children of the children of 1947 — look back at the decades gone by, we can draw lessons that may help us paint the future for our children.

To decipher the contours of this future, it is necessary to scan the past. On August 11, 1947, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah stood in front of the Constituent Assembly of the nation he had founded and said: “Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous, we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and especially of the masses and the poor. If you will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that every one of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste, or creed, is first, second, and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges, and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make.”

“I cannot emphasise it too much. We should begin to work in that spirit, and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community … will vanish … you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed — that has nothing to do with the business of the State… We are starting in the days where there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle: that we are all citizens, and equal citizens, of one State.”

“…[A]nd you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State… I shall always be guided by the principles of justice and fair play without any, as is put in the political language, prejudice or ill-will; in other words, partiality or favouritism. My guiding principle will be justice and complete impartiality, and I am sure that with your support and co-operation, I can look forward to Pakistan becoming one of the greatest Nations of the world.”

Pakistan one of the greatest nations of the world? Did the Quaid really mean that a nascent, poor, underdeveloped and insecure country could become one of the greatest nations of the world? Or was this term a mere rhetorical flourish aimed at boosting the morale of a population traumatised by the convulsions of the greatest migration of people the world had ever seen? Today the use of this term would be met with scoffs, sniggers and derision. Today the length and breadth of our vision starts at Pakistan being a doormat for big nations and ends at Pakistan being an expensive and well-knitted doormat for big nations.

And yet none other than the Founding Father himself looked forward to Pakistan becoming one of the greatest nations of the world. He knew he would never live to see this day, but he wished so. He dreamt so.

The Quaid was the product of his times and yet he saw farther, much farther than those of his times. “Great” Britain was the Imperial Rome of his times and he was deeply acquainted — perhaps even immersed — in the imperium of the empire. It was because he knew the British so well that he could fight them so well on their own constitutional turf. And yet the Quaid was also well aware of the ingredients that went into making Britain a global power.

Could he draw parallels for the country he created? He himself embodied values he mentioned in the speech to the Constituent Assembly, and he conceivably projected the same noble values on to the nation. It is safe to assume that he had thought long and hard about what kind of nation this new country of Pakistan should be. The Quaid must have framed his thoughts and ideas against the landscape of nations bestriding the world in his era. And what an era that was.

Imagine what the Quaid lived through. He was 28 years old when Japan launched a war against Czarist Russia and defeated it. He was 29 when Einstein proposed his theory of Relativity; 38 years old when the First World War started (10 million people died in the war); 41 at the time of Lenin’s revolution in Russia; 57 when Adolf Hitler was elected the Chancellor of Germany; 63 when Hitler invaded Poland and started the Second World War (60 million people were killed in the war); 68 years old when Japan attacked the USA at Pearl Harbour and dragged it into war; 69 years old when the Americans dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima killing 80,000 people in an instant; and the Quaid was 71 years old when he achieved the independent state of Pakistan.

When this 71-year-old man stood in front of the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947 he must have had a very clear idea of the direction he wanted this new country to chart. He had lived through an era that had rent asunder the traditional world order at the cost of 80 million lives; that had killed off the British Empire and laid the foundations of the American one; that had destroyed the Nazi phenomenon that was supposed to have lasted a thousand years and transformed Czarist Russia into Communist Russia. The Quaid had seen the rise of science and technology and amazing breakthroughs in fields like physics, medicine and telecommunications. So when he spoke about Pakistan becoming one of the greatest nations on earth, he had a fairly good idea of what went into making great nations. There was clearly a reason why he said what he said in that speech that August day.

Today as political pygmies roam this Quaid’s land, it may be useful to frame them against the colossus that Muhammad Ali Jinnah was, and then allow the horrible feeling of inadequacy to wash over you. This land should not be condemned forever as a doormat for great powers. The Quaid had a dream. The least we can do is not allow the pygmies to kill it off.

Published in The Express Tribune, December 25th, 2016.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS (14)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ