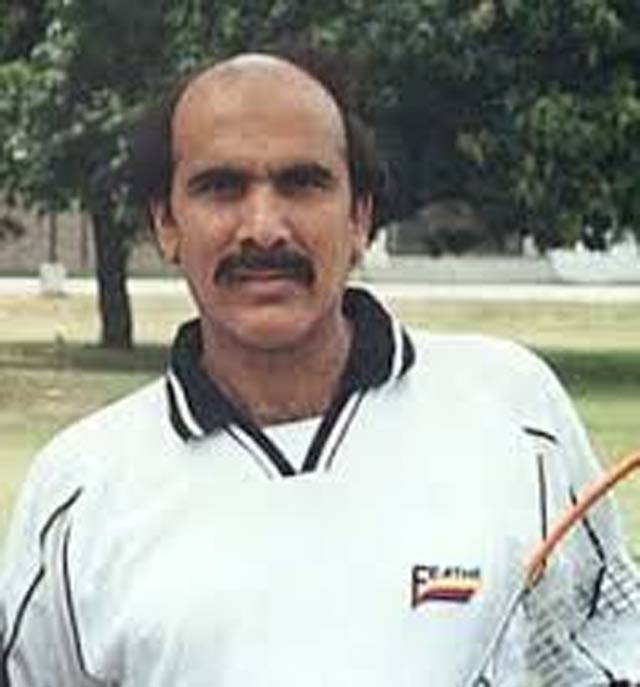

In his heyday, Allauddin was the second best squash player in the world — reaching two British Open finals. But he never won the event, nor did he breach the summit of world squash. For that, he is a man forgotten.

Squash — making a comeback

The British Open was squash’s holy grail before the introduction of the World Open and twice Allauddin came agonisingly close to etching his name in the pages of history. First in 1973, when he was defeated by Ireland’s Jonah Barrington, and then again just two years later when compatriot Qamar Zaman denied him in the 1975 final.

He now works at the Punjab Squash Association as its head coach but feels his life could have been so much more different had he managed to claim one of those two titles.

“In all these years, I’ve learnt that people only remember and respect world champions,” Allauddin told The Express Tribune. “I finished as a runner-up twice at world championships which is a big achievement. It pains me a lot to see former world champions standing in courts during ceremonies as chief guests, while I stand with the public. Every time this happens, I think about the what ifs and how my life would have been had I won a championship.”

Pakistan’s squash has been dominated by men from Peshawar but under Allauddin’s training, good players from Lahore have also started emerge. The likes of Asim Khan, Israr Ahmad, Kashif Shuja, Tayyab Aslam and Ali Bokhari have all shown they can compete with the best players of the country.

But Allauddin earns a paltry reward for his services, earning a salary of Rs40,000 at the Punjab Squash Association.

Jahangir Khan thinks international events can revive squash in Pakistan

“Rs40,000 per month is the sort of respect and remuneration legends get in Pakistan,” said Allauddin. “However, I’m thankful to Punjab squash that they are at least utilising my services and hope that the Pakistan Squash Federation (PSF) will look at my work and will appoint me as their head coach.”

Times are hard for Allauddin but he is grateful for what he has, having seen worse. “I’m thankful for what I have because I’ve experienced worse days in life,” he said. “When I started playing squash, I hardly had any money. Officers of the Punjab Squash Complex used to give me shoes, balls, rackets and even milk. The shoes used to develop holes because of cemented courts and my feet used to bleed. I went through eight or nine white shoes in a single month.”

Pakistan squash has a rich and proud history, having dominated the sport with an iron grip that is unrivalled across any other global sport. But even among the greats, Allauddin has a special place, having forged a name for himself while being from a city where squash is seldom played.

He recalls it was his father’s wish to see his son play squash, spurring him on with the feats of the great Khans that ruled the sport for decades.

But Allauddin and those Khans are now a thing of the past, and the 64-year-old feels Pakistan must invest in youth if it is to produce such greats again.

“The PSF has taken some good initiatives by introducing academies and giving contracts to players,” he said. “If all this took place 15-20 years ago, we would still be producing world beaters. In our day, PIA used to take care of everything — whether it be travel, food or our monthly incomes — but that doesn’t happen anymore and so the players suffer.”

Allauddin feels there is no substitute for hard work. “We still have good raw talent but players don’t want to train for four or five hours every day,” he said. “It’s not easy to become Jahangir Khan, Jansher Khan or Qamar Zaman without hard work.”

And if any player knows anything about hard work, then it is squash’s ultimate forgotten man; having come so close to etching his name among squash’s greatest, yet living to see his name lost in the pages of history.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 29th, 2016.

Like Sports on Facebook, follow @ETribuneSports on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

1721377568-0/BeFunky-collage-(18)1721377568-0-165x106.webp)

1732622039-0/Express-Tribune-(8)1732622039-0-270x192.webp)

1732608486-0/BeFunk_§_]__-(54)1732608486-0.jpg)

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ