Ghalib’s reign continues

151 years may have gone by but the master poet still rules supreme

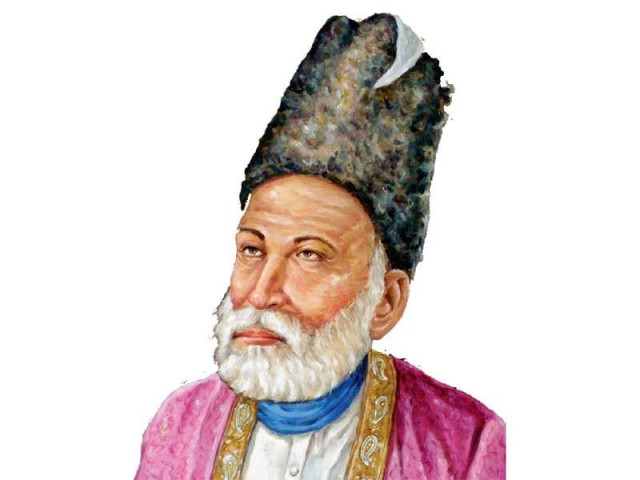

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib breathed his last on February 15, 1869. PHOTO: FILE

We might never know the intentions of an artist, yet we tend to draw conclusions about what exactly do they mean to say. These conclusions are cemented if the artistic work’s denotation is in synchronisation with our own understanding of how things ought to be: good or bad, sensible or nonsensical. This synchronisation of ideas is what gives us our masters and maestros.

Ghalib doesn’t, however, work that way. In just one collection of poetry, he covers such a vast range of human emotions and fallibility that one often looks through his verses to find a name to a feeling. Is it the rustiness of longing for your beloved’s lock of hair to move or the blood that doesn’t run through the veins but oozes out of the eyes? Ghalib had it all sorted at a time when India was divided on whether to submit to the Raj or to contest it.

Often labelled apolitical and numb to his circumstances, Ghalib actually did rise up to the task during the 1857 War of Independence. He obviously didn’t go out on the street to shout slogans; he was probably gulping down a bottle of ‘angrezi sharab’ (English liquor) while that was happening. But he did express his disappointment over Bahadur Shah Zafar, the Mughal emperor whom Ghalib tutored in the Persian language.

Zulmat kaday mae meray shab-e-gham ka josh hai,

Ek shamma hai daleel-e-sahar, so khamosh hai!

[In my darkness-chamber is the ebullience of the night of grief,

A single candle is a sign of the dawn — thus it is silent]

Here Ghalib compares the last Mughal emperor to a dying flame and how all hopes of countering the Raj will die with the submission of the Mughal.

His humility as a person coupled with a craving for any form of intoxication was what made Ghalib the king of Chandni Chowk in Delhi. It was perhaps the first time that a person of such linguistic capabilities was rising from the streets and not from the emperor’s court where stalwarts like Hazrat Ibrahim Zauq would gather. His fondness for the street once resulted in him being arrested for gambling but the player of words that Ghalib was, even found a way out of it. “Main adha Musalman hoon. Sharab peeta hun par suar nahin khata [I am half Muslim, I drink but I don’t eat pork],” responded Ghalib when he was quizzed over the act. Hearing him reply, the judge laughed and let him go. This event of his life is beautifully documented in Gulzar and Kaifi Azmi’s tele-play on the poet.

There were only a handful of happy moments in Ghalib’s life and most of them short-lived. Grief circumambulated him like the earth circumambulates the sun; he extracted life from its light, yet maintaining distance, for any closing up would result in complete annihilation. Not one of Ghalib’s seven children survived beyond infancy, leaving a void in his life that made his dispute with the Creator a permanent fixture.

It was perhaps this sense of loss that fuelled Ghalib’s fire, so much so that he started taking pride in his loss and depravity. He himself says, “Barq se kartay hain roshan, shamma-e-matam khana hum [We light the candle of our chamber with the lightning blast].” This sense of superiority over his sorrow is what makes him so unpredictable and special.

Published in The Express Tribune, February 16th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ