A nation, in the words of political scientist Benedict Anderson, is an imaginary political community, explained the moderator Fahad Desmukh. “It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know all their fellow members, speak to them or even hear them,” he quoted Anderson. “Yet in the minds of each lives their image.” This kind of thought is a product of modern society, facilitated by mass media and technology.

So what place does nationalism find in the school of tomorrow with respect to the curriculum being taught in schools, Desmukh asked the panelists.

Talking it out: Pakistan’s fear of expressing itself

For Yusuf, Pakistan’s various attempts to create a monolithic nation have caused more harm than good. “Pakistan was created on the basis of faith, soon after which the founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, said that religion would have nothing to do with governance,” she related. “Jinnah said that Urdu will be the national language of Pakistan, even when 56 per cent of the Pakistanis at the time were Bengali-speaking.” This created a rift on the basis of language. After the separation of East and West Pakistan in 1971, we resorted to religion, she lamented. “Our leaders often proclaim ‘Hum sub Musalman hain’ [We are all Muslims],” she smiled. “What about the non-Muslim Pakistanis? Where do they fit into this narrative?” she asked.

The next panellist, television anchor Shahzeb Khanzada, agreed with Yusuf. The problem with Pakistan is that religion has been misused to set up a national agenda, he said. “After the separation in 1971, we had a chance to address the issue of nationalism and identity. But then we turned to religion,” he lamented.

“I studied in class nine that Mehmood Ghaznavi came from Afghanistan and defeated all the Hindus,” he reminisced. The story had confused him at the time. How was the destruction caused by an Afghan invader good? Only because he was Muslim? he wondered. “The majority of our population thinks religion is nationalism because it has been used by the state so many times,” said Khanzada. “We have become a national security state and the state is now using lies and taking the cover of Islam to further its agenda,” he lamented.

For Khanzada, the only way out of the mess is to erase the lies and focus on the truth. “Your books are full of lies,” he accused. “If German children were to study that the Nazis were good, would they prosper as a nation?” he questioned. “We must tell the truth.” Admittedly, this would be a difficult task as Pakistan has turned into a security state, he said. “We are continuing to tell these lies to safeguard the interests of certain groups of people,” he added.

The third panelist, Saima Zaidi, who is an associate professor of communications design at Habib University, stressed that one must not underestimate the student of tomorrow when it comes to nationalist ideology. “The student of tomorrow has many sources of information,” she said, furthering Khanzada’s point.

So what is the place of nationalism in today’s society after all? Yusuf believes the notion must be done away with altogether. A person may identify as a Pakhtun and as a Pakistans at the same time,” she explained. “I don’t think they are contradictions in any manner.”

Zaidi agreed, suggesting inculcating the idea of cultural pluralism into the curriculum. Adding to the point, Yusuf described the situation in Balochistan, where people described as insurgents were demanding their basic rights. “It is tragic that it is being seen as a security issue, rather than a matter of rights,” she lamented. The Baloch are humiliated even for the way they dress. As a result of such actions, the sense of Baloch nationalism is getting stronger even in those who were not involved in the insurgency, she claimed. “It is unfortunate that we did not learn any lessons from Bangladesh.”

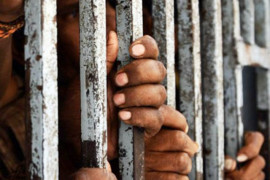

For Khanzada, however, the problem lies in the misuse of religion to further the state’s agenda. “When I was studying at a madrassa, there were two boys of hardly 13 years of age who had undergone training with the Lashkar-e-Taiba,” he reminisced. “They were praised and lauded by everyone in the madrassah and their skills with a revolver were a matter of reverence among our peers.”

Khanzada lamented that, as a student of the 1980s, Ziaul Haq not only confused his national identity, he also distorted his religious beliefs. “My parents taught me Islam was a religion of peace. Ziaul Haq taught me jihad and terrorism.”

Yes, we Pakistani and we are Muslim. But the misuse of religion to dictate foreign policy and security policy for the furtherance of a particular agenda is what has got us in this mess.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 29th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ