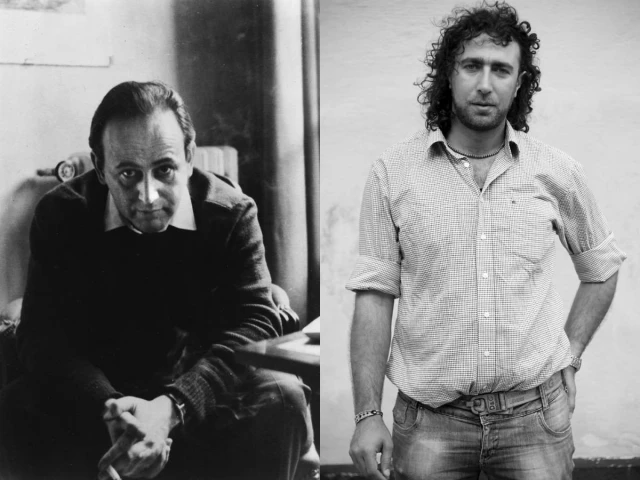

Upon news of No Other Land’s (2024) Oscar win, I am thinking of Black Milk. Of Ghayath Almadhoun, Palestinian poet born in a refugee camp in Damascus, now living in Sweden, and of Paul Celan, French poet born in Romania, survivor of the Holocaust.

Where the two co-directors, Basel Adra and Hamdan Ballal, work together to highlight the differences between the current lived realities of the Israeli and the Palestinian, the poets work together to reiterate the role of the European in all this oppression– then, against the Jew, now, against the Palestinian.

If No Other Land shows that there is the possibility of brotherhood between the two supposed enemies, the poems tell us that this brotherhood is a recognition of what it means to be belittled to a camp, but at different points in time.

Celan’s poem Death Fugue speaks of and from the concentration camp, and Almadhoun’s Black Milk of the refugee camp and the guilt-ridden world outside it.

Almadhoun not only remembers Celan, naming his poem after Celan’s strongest image in Death Fugue, but also identifies with him, hears him call to Almadhoun, and draws upon his experience (and the language used to describe that experience) to make sense of his own present. He writes:

“And Paul Celan emerged from the River Seine

And with his wet hand tapped me on the shoulder

And in a trembling voice whispered in my ear

Don’t drink the black milk

Don’t drink … the black… milk

Don’t drink

Don’t

And disappeared among the groups of Syrians marching northwards.”

What is the ‘black milk’ and why is Celan advising Almadhoun not to drink it?

Celan begins his poem with, “Black milk of morning we drink you evenings // we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night // we drink and we drink.”

This is repeated at the beginning of all four stanzas, clearly enunciating for us the repetition of a miserable routine. All the mornings and nights are being drunk before they even arrive.

He speaks of a man who ‘plays with the snakes’ and ‘whistles his jews to appear let a grave be dug in the earth,’ pointing to the very cruel, fascist treatment of Jews.

So then of course it makes sense that Almadhoun is remembering Celan as the guilt of leaving his country is overwhelming him. He first mentions Celan in the poem with an explicit comparison, a blatant display of the repetition of history:

“and my European friends withdraw from me quietly, and I remember how the Europeans withdrew from their Jewish friends seventy years ago, and I remember the black milk.

And I try not to remember Paul Celan.”

Why does Almadhoun pick Celan, out of all people, knowing his Jewish identity, when so much of his trauma and conflict with identity is a direct result of attack, apartheid, and oppression at the hands of Israel?

It serves as a reminder that a lot of war-related traumas and memories are similar, no matter the identity.

Cathy Caruth, in her ‘traditional trauma theory,’ suggests that ‘history fails to adequately represent traumatic events such as war or genocide, since any representation is a type of fiction.’

This begs the questions: what is adequate representation and to what extent does it matter? Criticism of Caruth by feminist, race, and postcolonial theorists argues regarding the social and cultural implications of trauma.

For example, J. Brooks Bouson, in Quiet As It’s Kept (2000), writes about the portrayal in Toni Morrisson novels of trauma carried out by racist institutions and practices. These are systemic events and actions that have universal impacts on the oppressed groups.

Almadhoun, being an Arab and coming from a country targeted by the Israeli Jew, empathizes with a Jewish man and uses his experience as a lesson and reminder that Almadhoun’s refuge in a foreign country for safety is reasonable no matter the associated guilt, as he knows they both have faced similar traumas.

There is a resonance with an identity he is supposed to dislike, nowhere near the resonance he feels in the present with European people around him.

In fact, the closest his European friends come to relating to his trauma is when they ‘fantasize’ about the Twin Towers ‘collapsing.’ Almadhoun and Celan, who share more tangible and bodily consequences, are hence united in their intense emotions of loss, guilt, and conflict in identity.

Remembrance of the Holocaust and the vile treatment Jewish folks have been subjected to in history can look like the justification of an Israeli occupation in the present, or it can look like solidarity and carrying lessons from the past.

Black Milk brilliantly draws connections between a Palestinian present and Jewish past, and through No Other Land, we see that the Jewish past is no longer the Jewish present.

The need for a land for Jews does not look the same today as it did seven decades ago. It never should have come at the cost of the Palestinian people, but especially now, as we witness this genocide, the imbalance is glaring at us.

We must empathize with the reality of Jews during the Holocaust, and may even derive solace with current realities through it as Almadhoun does, but we must not take that to mean that history is present.

If history is bleeding into the now, it is in the ways that colonization is persisting, in the ways that the white man maintains his position at the expense of thousands.

To achieve real brotherhood, real solidarity, real camaraderie, systems that have brutalized over and over, from one victim to the next, need to disintegrate. What we can identify so easily in history and present is the ever-common denominator – the backhand of the white man.

It is imperative that Israeli citizens are able to recognize that their present-day reality is not what it was 75 years ago, and their state is only a medium that fulfills the white man’s dream.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ