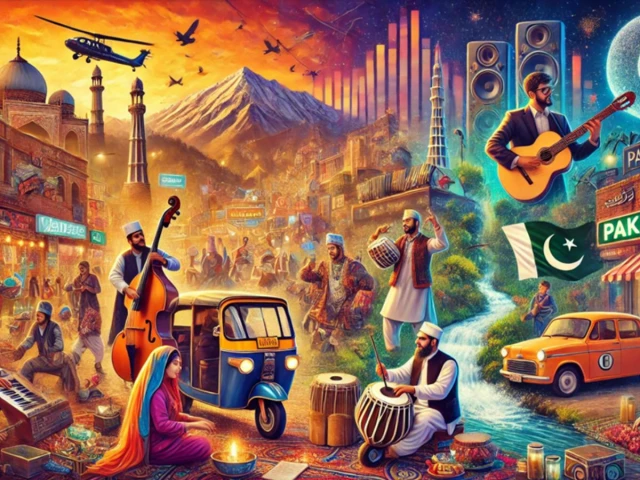

If there’s one thing Pakistan has consistently done right, it’s music. Despite political turmoil, censorship crackdowns, and an overall identity crisis every other decade, Pakistani artists have created magic—songs that define generations, voices that refuse to be silenced, and beats that make even the most reluctant uncles tap their feet.

But how did we get here? How did Pakistan go from the classical era of ghazals and qawwalis to pop anthems, rock revolutions, and global Spotify sensations?

Buckle up, because we’re taking a deep dive into the Pakistani music scene—from the 1980s to today, where indie artists are breaking records, Coke Studio has basically become a religion, and folk traditions continue to thrive alongside modern beats.

Let’s start with the queen herself: Nazia Hassan.

Before her, Pakistani music was mostly film songs, ghazals, and qawwalis. Beautiful, yes, but also a bit too serious. Then in 1981, Nazia and her brother Zoheb Hassan dropped Disco Deewane, and suddenly, Pakistan had its own pop revolution.

This wasn’t just a hit—it was the hit.

The album topped charts in 14 countries, including India, making Nazia the first Pakistani pop superstar. Her voice, combined with British-Indian producer Biddu’s disco beats, was the fresh sound Pakistan didn’t even know it needed.

But here’s the catch: this was General Zia-ul-Haq’s era, a time when anything remotely fun was frowned upon.

Censorship was at an all-time high, and anything “Western” was seen as corrupting young minds. Yet, despite this, Nazia’s music flourished, and she became a household name.

The ‘90s were wild, and Pakistani music went from an underground movement to absolute mainstream domination. Thanks to the rise of PTV’s music programs and cassette culture, pop and rock bands became massive.

You simply cannot talk about Pakistani music without Vital Signs. Their song Dil Dil Pakistan (1987) became a national anthem in its own right. Imagine a country obsessed with patriotic marches suddenly getting a soft rock song about love for Pakistan—it was a game-changer.

The band’s frontman, Junaid Jamshed, became a cultural icon, and their music blended Western influences with local sensibilities. For the first time, Pakistani youth had their own voice, their own music, their own aesthetic.

While Vital Signs kept pop music alive, Junoon took a different route: Sufi Rock. Led by Salman Ahmad, Junoon blended electric guitars with poetry, and songs like Sayonee and Jazba Junoon became anthems of resistance.

At the same time, Strings emerged as another powerhouse, producing Sar Kiye Yeh Pahar—a song so poetic and nostalgic it could make even Karachi’s traffic feel romantic.

The ‘90s were also the MTV generation, and Pakistani music was booming. Bands like Awaz (Haroon’s old band), Ali Haider, and Fakhr-e-Alam all contributed to this golden age.

Just when you thought Pakistani music couldn’t get better, the 2000s happened.

Noori came in with Suno Ke Main Hoon Jawan, making pop-punk anthems a thing. Entity Paradigm (EP), featuring a young Fawad Khan, introduced nu-metal to Pakistan. Aaroh, Mizmaar, and Fuzon blended Western rock with classical influences, creating a sound that was uniquely Pakistani.

This was also the post-9/11 era, and Pakistan was once again dealing with political instability, media restrictions, and the war on terror. Music became a form of rebellion, with artists addressing social issues, youth frustration, and the need for identity.

But despite their success, many bands started to break up. Junaid Jamshed left music for religion. EP disbanded. Even Junoon faded. It felt like Pakistani music was about to enter a dark age.

And then, Coke Studio happened.

Launched in 2008 by Rohail Hyatt (yes, the same guy from Vital Signs), Coke Studio became THE biggest music platform in Pakistan. It took folk music, classical influences, modern beats, and put them in one big experimental pot.

This era gave us legends like Abida Parveen, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, and Ali Sethi, while also reviving folk music through artists like Mai Dhai and Saieen Zahoor.

At the same time, the indie scene exploded.

Hasan Raheem introduced lo-fi pop and became an instant hit. Young Stunners made Urdu rap mainstream. Shae Gill dropped Pasoori, which became a global phenomenon, proving that Pakistani music doesn’t need Bollywood to make it big.

With platforms like Spotify, YouTube, and SoundCloud, artists no longer needed record labels. They could release music independently, and the world was listening.

But let’s not forget Pakistan’s deep-rooted cultural music traditions, which have shaped its sound for centuries.

One of Pakistan’s greatest musical gifts to the world is qawwali—a Sufi devotional music form that has survived for centuries. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan took it to an international stage, blending traditional poetry with a spiritual intensity that still leaves people mesmerized.

Today, artists like Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen, and Fareed Ayaz & Abu Muhammad continue this legacy, proving that qawwali will never go out of style.

Pakistan’s regional folk music is just as important.

Sindhi folk music, with its deep-rooted poetry and Alghoza melodies, is best represented by Allan Fakir and Mai Dhai. Balochi folk music, featuring instruments like the Soroz and Dambura, tells the stories of the desert. Pashto music, driven by the Rubab, has given us legends like Sardar Ali Takkar and modern stars like Gul Panra. Punjabi folk, full of dhol beats and bhangra energy, remains popular worldwide, thanks to artists like Attaullah Khan Esakhelvi and Arif Lohar.

But the music industry hasn’t been free from political interference.Let's take a quick looks at this:

- Zia’s era (1980s): Banned concerts, censored lyrics, and discouraged anything “Western.”

- Musharraf’s era (2000s): A boom in private channels helped musicians, but political instability still created uncertainty.

- Post-2010s: Music festivals were shut down, concerts were banned, and yet, musicians found ways to keep going.

Artists like Ali Gul Pir have used satire in rap to criticize society. Rock bands like Laal have openly sung about political injustice. The resistance is still alive.

From Nazia Hassan’s disco beats to Young Stunners’ rap bars, Pakistani music has evolved, adapted, and thrived despite all odds.

So the next time someone tells you "Pakistani music isn’t what it used to be," just send them a playlist. From Sufi to rock, pop to rap, and deep-rooted folk traditions, we’ve got something for everyone.

The legacy continues, and it’s louder than ever.

COMMENTS (3)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ