In Pakistan, the media has taken on various roles, often acting as analyst, policy maker and even judge. At times it has lost the entire notion of censorship and theconcept of contextual objectivity (as difficult as that may be). Over the past few years, soon after the media boom occurred in Pakistan during Musharraf's regime, we, the viewers, have become accustomed to the daily blood and gore, the loud shrill voices of our anchors, the filmy Star Plus soundtracks played during headlines, the sheer sensationalised repetition of one political hoo-haa after the other. I have repeatedly heard that this drama sells like hot naans to the masses in Pakistan. Like entertainment. But, just because a news story sells does not make it a good story. This is the distinction our media personnel find hard to grasp.

Let me mention some examples of journalism that have been rather frustrating, for me at least.

The Airblue crash of 28 July 2010 was a tragic incident that took the entire nation's spirits down with it. It personally affected many of us whose families, friends, or acquaintances were on that plane. Granted, our media acted well in terms of informing us of the death toll and the inquiries that followed. What was extremely disgusting was to watch reporters and cameramen shove their equipment in the faces of grieving family members merely hours after the crash, minutes after they heard news of their loved ones. The notion of privacy seemed to have evaporated.

A more recent example has been that of Mr Shamsul Anwar and his reportedly fraudulent story of the kidnapping of his daughter. The story was not verified and many a people in Pakistan and abroad donated funds for Mr Anwar’s daughter. Now, although Pakistanis feel proud for standing together for a cause, most of us have been left feeling foolish.

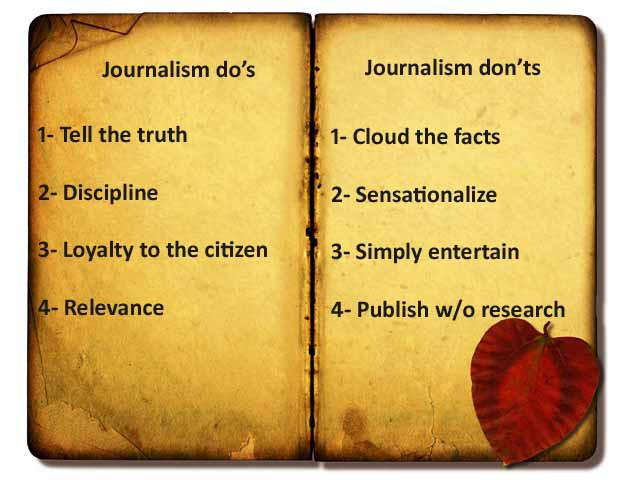

Irresponsible journalism has affected scores of people in Pakistan, perhaps because most journalists have never studied the subject itself. Admittedly, I am no expert in journalism, but I would like to take up this virtual space to list nine principles of journalism that should be etched in the minds of all journalists.

In 1997, the Committee of Concerned Journalists began their research to outline a Statement of Shared Purpose. After four years, the original Statement of Shared Purpose outlined nine principles of journalism to comprise what could potentially be described as the theory of journalism.

- Journalism’s first obligation is to the truth (read: assemble facts and verify them)

- Its first loyalty is to the citizen (read: not to any political party or politician)

- Its essence is the discipline of verification (read: separate yourself from fiction, propaganda, and entertainment. Refer to principle 1. Also refer to Shamsul Anwar)

- Its practitioners must maintain an independence from those they cover (stay neutral; stay fair. Your credibility as a journalist comes from accuracy, not your devotion to Imran Khan or your fondness for the judiciary)

- It must serve as an independent monitor of power (read: journalism can serve as a watchdog over those in power; that freedom need not be exploited!)

- It must provide a forum for public criticism and compromise (read: we love discussion. Najam Sethi, though whatever his background may be, has one of the most peaceful talk shows. Discussion and foul-mouthed arguments during live broadcasts are two different modes of communication.)

- It must strive to make the significant interesting and relevant (read: entertainment engages your audience; news enlightens it. Understand the difference.)

- It must keep the news comprehensive and proportional (read: know your demographics.)

- Its practitioners must be allowed to exercise their personal conscience (read: carry a moral compass)

A few weeks ago, as I worked on my computer, my brother-in-law was intently tuned into an evening talk show airing on a Pakistani news channel in London. Four participants, including one female host, went at each other like raging bulls heading for a red flag. After20 minutes of listening to pure noise blasting from his television set, I turned to my brother-in-law and inquired:

‘Have you understood anything anyone has said since this show started?’

He threw his head back and chuckled:

‘No, but it’s entertaining’.

[poll id="110"]

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ