In 1989, Syed Yahya Shah Al-Hussaini – a local political and religious leader from the Bar Valley in Gilgit-Baltistan, northern Pakistan – came up with a rather unusual conservation trade-off: helping the Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica) in the valley thrive by allowing it to be hunted for its horns. Trophy hunting had been banned in Pakistan in the early 20th century after the excesses of organised hunting expeditions (shikars) during the British rule had wrought havoc on the endemic big-game animal population, driving them to the brink of extinction. This was unfortunate because ungulates have great significance for local communities. They provide income along with meat and hide to withstand the winter cold. Ungulates are associated with fairies in folklore – a symbol of majesty – and the markhor is Pakistan’s national animal. Community hunting used to be for subsistence; hunters performed special rituals before embarking on expeditions.

Syed Yahya Shah could see that a prolonged, complete ban on hunting would have deep, unseen impacts on livelihoods and traditions. The ban was also spilling over into increased illegal poaching. So, he proposed that the Bar community should receive special government dispensation to open their valley to commercial trophy hunting – if they used the proceeds towards wildlife conservation and community development. Foreigners would pay a premium price to hunt a limited number of Siberian ibex each year in designated zones. The hunters would take the trophy (the majestic head with spiral horns), while the community would keep the meat. The notion was that the incentive could help curb excessive poaching and strike a balance between the sustainable use of wildlife resources and economic gains.

There is of course much debate about the morality, economics, and efficacy of trophy hunting for conservation. Critics have derided the practice as a bygone colonial relic (fueled by masculinity and oppression) that does little to help wildlife conservation. They point to examples of how big-game hunting zones in Africa are being abandoned because big-game has been hunted out of these areas. They claim that the money intended for communities and conservation efforts ends up lining the pockets of a few individuals. There is also the complex issue of the ethics of hunting animals for sport: Do the ends really justify the means?

Yet, it cannot be entirely dismissed as a conservation tool either. The success of a community-based trophy hunting programme could very well depend on the ecological circumstances and management model in place. Even major conservation organisations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) argue that properly managed and science-based trophy hunting can benefit wildlife. A complete ban on this type of conservation can also be considered a form of neo-colonialism, with Western environmentalists dictating their agenda and models of conservation without considering the historical devastation of wildlife by colonial extraction, without heeding the needs of local communities, and without examining unique circumstances of certain habitats and wildlife populations.

Syed Yahya Shah broached the possibility of starting a community-based trophy hunting programme because he saw its utility for his people. He drafted a proposal after seeking the counsel of Ghulam Rasool, Divisional Forest Officer of the Gilgit-Baltistan Forest and Wildlife Department, and Shoaib Sultan Khan of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) – the only organisation back then engaged in social mobilisation efforts for rural development in Gilgit-Baltistan. The AKRSP forwarded his proposal to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and then to WWF-Pakistan. This group of conservation organisations approached Ashiq Ahmed Khan, an eminent conservationist then affiliated with the Pakistan Forest Institute, Peshawar, to conduct a situational analysis of the proposal and review its benefits for the Bar community and the ungulate populations.

Although there was a complete ban on hunting and export of mammals in the country, there were two precedents for trophy hunting: in the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) and in Torghar, a tribal area in Balochistan. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Chitral Gol National Park authorities hunted a Kashmir markhor (Capra falconeri cashmiriensis) in a buffer zone. Fifty percent of the revenue from the hunt was supposed to be invested in the development of the community living within the buffer zone. This never happened. The story was the same in Balochistan. Tribal leaders tasked with protecting the Sulaiman markhor (Capra falconeri jerdoni) through a strong watch-and-ward system in the Torghar area of Qila Saifullah were involved in trophy hunting. The tribal leaders kept the revenue for themselves. They did commit a part of the revenue to the government if it legalised trophy hunting, but they did not follow through with this pledge when the federal cabinet finally lifted the ban.

The programme in Gilgit-Baltistan needed to set a different example.

Studying the proposed programme’s suitability for the Bar Valley

In 1989, Ashiq Ahmed Khan visited the Bar Valley with representatives of the Gilgit-Baltistan Forest and Wildlife Department, WWF, and AKRSP to understand whether Syed Yahya Shah’s proposal would have its intended impact. Khan surveyed nearby catchments where trophy-sized animals were sighted close to human settlements. Studying the ibex population, he decided that for an ungulate to be considered for trophy hunting, it should be over nine years old, with horns larger than 40 inches. (The estimation is done by counting rings on the horn by professional hunters using binoculars.) He expected that hunting old bucks would do the least harm to the species (although this has been challenged on various grounds and could potentially be influenced by various other factors).

Based on the sightings of ibex, Khan discussed hunting-related matters with the local community, covering (among other things) the nature and scale of community hunting; reasons for hunting; numbers, type, age, and sex of ibex and markhor usually hunted; quantity of meat obtained per animal; alternatives to meat; and local meat prices. The experts focused on how increasing the prey population through trophy hunting-based conservation could reduce human–wildlife conflict (loss of livestock by predators and retaliatory killing by the community) by reducing poaching, increasing natural prey numbers for predators, and increasing community tolerance for predators. Khan concluded that through government-regulated trophy hunting, the community could reap more equitable benefits and assume greater ownership in wildlife conservation efforts. Based on years of interactions with the community, he knew that communities were hunting mostly to secure meat for their families and the gains from a regulated programme would benefit every family, whether they were involved in hunting or not. This would also deter illegal hunting. The trophy hunting revenue would be spent on biodiversity conservation and community development projects. Ashiq Ahmed Khan shared his report with the conservation organisations involved, and this formed the basis of the first community-based trophy hunting programme in Gilgit-Baltistan.

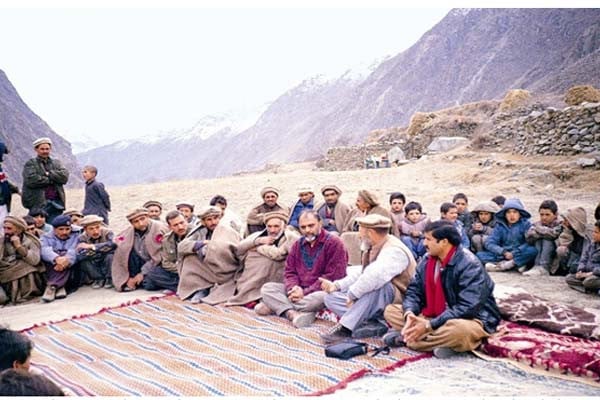

Representatives from WWF-Pakistan and AKRSP meeting the Bar community for the community-based trophy hunting programme in the early 1990s. (Photo: Nasir Azam/WWF-Pakistan)

Getting the programme started

As the federal cabinet had imposed a ban on the hunting of mammals, the programme could only be operationalised once the ban was lifted. Shakeel Ahmad Durrani, the then Chief Commissioner of Northern Areas (now Gilgit-Baltistan), sought approval of Ashiq Ahmed Khan’s proposed programme from the federal government. The proposal recommended a 75%/25% split of the revenue between the community and the government, respectively. The summary was approved in 1992 by the then Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif. An amendment signed in 1995 by the then Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, increased the community share of the revenue to 80%.

WWF-Pakistan finally implemented the community-based trophy hunting programme in 1991. During a formal gathering in Gilgit-Baltistan, the Bar community received a loan as a conservation trade-off to stop hunting and buy meat for their families to tide over the long harsh winters. In return, the community pledged to stop hunting markhor and ibex for two years, so that numbers of these ungulates could cross the threshold (of 4%) for trophy hunting. The local community returned the money after the first hunt, and this sum was donated towards the construction of a health facility in the Bar Valley.

The IUCN and AKRSP organised a comprehensive survey in Gilgit-Baltistan in 1992 to identify various sites that could become the target of future conservation interventions with a focus on trophy hunting. On the basis of that assessment, the Government of Gilgit-Baltistan approved the trophy hunting of Siberian ibex in 1993 and the IUCN launched a biodiversity conservation project in Gilgit-Baltistan in 1994, which laid the foundation for the community-based trophy hunting programme. Such efforts led the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to approve trophy hunting of 12 markhor each year in Pakistan (four permits each for Astore markhor in Gilgit-Baltistan, Kashmir markhor in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Sulaiman markhor in Balochistan) during the 10th meeting of the Conference of Parties in Harare,1997.

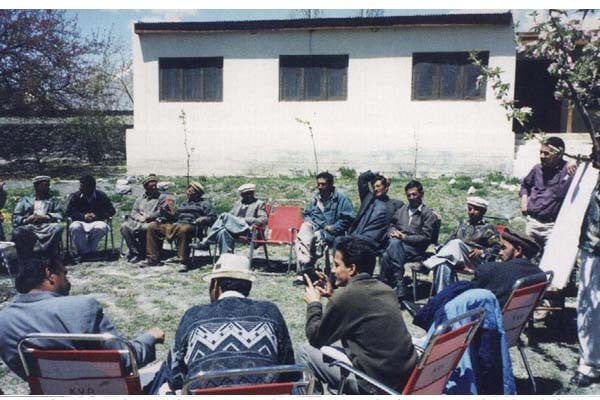

Staff from the Mountain Area Conservancy Project – a GEF/UNDP-funded project implemented by IUCN and WWF (1999–2006) – meeting local communities in Gojal Conservancy, Gilgit-Baltistan, for replication of the community-based trophy hunting model in their area. Hunza, June 2000. (Photo: M Zafar Khan/WWF-Pakistan)

A successful model for Gilgit-Baltistan

Pakistan’s model of community-based trophy hunting programme is purely an incentive-based conservation approach carefully designed to strike a balance between the conservation needs of mountain ecosystems and the livelihood needs of marginalised communities that have been coexisting with wildlife for centuries. The ecological impacts of the trophy hunting initiative, especially on the species of markhor and ibex in the programme area, have been significant. There are now more than 50 designated community conservation areas, covering more than 30% (around 21,750 sq km) of the total land area of Gilgit-Baltistan.

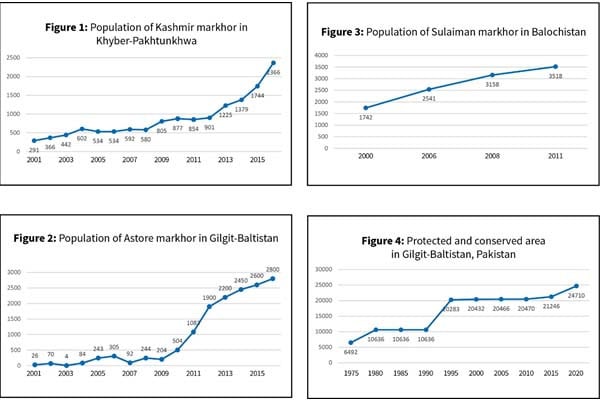

Since the trophy hunting scheme has been operational, the poaching of wild animals has decreased significantly, which has contributed to a significant increase in markhor and ibex populations across the mountainous region of Pakistan. The population of Astore markhor (Capra falconeri) in Gilgit-Baltistan increased from 1,900 in 2012 to 2,800 in 2016. The population of Kashmir markhor in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa increased from 2,493 in 2009-10 to 4,878 in 2016-17. In Balochistan, the population of Sulaiman markhor increased from 1,742 in 2000 to 3,518 in 2011. There is also anecdotal evidence to suggest that trophy hunting has been beneficial for endangered species such as the snow leopard since their natural prey populations have increased. This has meant that the incidences of such predators encroaching on farmlands and killing livestock has decreased.

Source: Provincial governments of Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Gilgit-Baltistan (2018)

The programme has also led to better community programmes, infrastructure, and services for communities and the initiation of conservation efforts. Under the programme, foreigners can acquire a trophy hunting license for Siberian ibex for only USD 3,600, with the markhor commanding USD 100,000. With the local communities receiving 80% of the revenue, the economic benefits of the trophy hunting programme are naturally substantial. From 1995 to 2020, the programme has generated USD 4.86 million for Pakistan from the sale of trophy hunting permits for only markhor, out of which USD 4.3 million has been invested in the social, economic, and environmental development of the local communities.

Using about 30% of the revenue, local communities grow fodder and raise plantations on wastelands for habitat improvement, organise livestock vaccination campaigns to prevent disease transmission from domestic to wild animals, conduct cattle breeding campaigns, maintain joint watch-and-ward systems for wildlife protection against poaching, and improve the design of corrals in pastures to make these predator proof. Around 70% of the revenue is spent on a range of social and economic development activities, from repairing irrigation channels to community school buildings, basic health units, educational stipends and scholarships, soft loans to women for micro businesses, and improving farm-to-market infrastructural connectivity.

Given the nature of the conservation model, there has naturally been an outcry over the trophy hunting programme’s very existence in Pakistan, both regionally and internationally. There have been criticisms of poor management and misappropriation of the funds generated. However, Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change has hailed the programme as a “success story” in terms of conservation. CITES has welcomed the programme’s success in Pakistan, but it has also noted some gaps, including the lack of accurate information to understand the effect of trophy hunting on herd structure and size, weak policy implementation, lack of transparency, and corruption. CITES officials have signalled that they could consider the Government of Pakistan’s request to increase markhor hunting permits if the CITES Animals Committee evaluates the status of Kashmir markhor in the country and recommends the increase. The Government of Pakistan’s announcement to conduct an audit of trophy hunting revenues is a welcome move which will help ensure transparency. This is where the private sector can contribute to the efficacy of the trophy hunting programme as well as community-led conservation initiatives, by ensuring scientific understanding of the trophy hunting programme and improving transparency, accountability, benefit sharing, and environmental stewardship.

There is much to admire and learn from the success of the community-based trophy hunting programme in Gilgit-Baltistan. However, before it is promoted as a conservation panacea for the entire Hindu Kush Himalayan region, or indeed the world, we should remember how much thought, examination, and scrutiny Syed Yahya Shah’s proposal went under before it finally came to fruition – and how much there is left to be desired.

COMMENTS (7)

For argument s sake lets assume there s nothing ethically and morally wrong with hunting. Even then these magnificent specimen with unique and dominating physical features and attributes such as oversize horns should not be hunted. These animals are meant to breed and pass their superior genes onwards. It is never a good hunting practice to target the Alpha of a species specially for sports.

Two key persons in promoting the idea were late Hussain Wali Khan ex-GM Manager AKRSP and Haji Ghulam Rasul ex-DFO .

Trophy hunting is haram from Islamic point of view. Hadith Whoever kills a sparrow or anything bigger than that without a just cause Allah will hold him accountable on the Day of Judgement. Benefiting a local society from hunting is not a just cause as it can be benefitted by eco-tourism and especially luxury eco-tourism.

I agree. Luxury tourism can match and in all likelihood surpass monetary benefits obtained through trophy hunting.

A fine article clearly showing the pragmatism and hard work behind regulated sustainable trophy hunting. Few publishers in the West have the honesty to tell such truth.

Promote tourism in these areas. Setup public private sector collaboration to generate funds for social economic and environmental development of the local communities rather than putting a prize on your honor. Pakistan has lost moral compass. No matter how you slice or dice it. It is ethically and morally corrupt practice to put a prize on your national animal. PERIOD

Truely agreed.

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ