Abul A’la Mawdudi was perhaps the most important Islamic thinker of the 20th century in terms of the impact that his Islamic exposition had in his own region of the Indian Subcontinent, the Arab World, and also amongst the Muslim diaspora in the West. His political interpretation of Islam has gained widespread currency amongst all Muslim societies. In one of his columns, the Pakistani writer, Nadeem Farooq Paracha, drew a very interesting analogy; he wrote that Mawdudi is to Political Islam, what Karl Marx was to Communism[i]. I will start off by completely agreeing with that analogy. In the ensuing text, readers will notice that I frequently invoke that comparison. I do that because it is, I believe, essential to understanding the phenomena of Political Islam.

Mawdudi was born in the year 1903, in British India, to a traditional Islamic family, which traced its roots back to a famous Sufi mystic of the 11th century (Mawdood Chisti – after whom Mawdudi was named). Yet, very early, Mawdudi relinquished his family’s Sufi affiliations and became interested in exploring the new ideas and movements that were slowly engulfing the Indian political and social discourse. He was particularly intrigued by the Secularist and Marxist tendencies, which prompted him to read the main texts of such philosophies personally. He did receive traditional Islamic schooling but never disclosed this to his audience because, first, he took great pride in being considered an autodidact (which he was to a great extent), and secondly, because he regarded the traditional clergy and its reliance on an antiquated approach to Islam, with great disdain. He realised, perhaps accurately so that in order for Islam to retain its prominence, it can no longer be presented as a mere spiritual faith that had nothing to say about the new socio-political ideas that had emerged during the last couple of centuries, and he took it on himself to study these new trends that were slowly making their pathways into the Indian Muslims’ socio-political discourse. One writer recalled that when he visited Mawdudi, he found him completed surrounded by English books, most of which were Communist texts[ii].

This explains why his Political interpretation of Islam bears a great resemblance to Marxism-Leninism. Despite his apparent disgust for Communism, he was still fascinated by many of the communist ideas, and this fascination was quite apparent in the interpretation of Islam that he proposed, the basis on which he founded his Islamic Political party, and the plans he laid out for his future Utopian Islamic society.

In both totalitarian variants of Socialism, Bolshevism and Fascism, a chosen part of mankind was deemed the rightful heir to establish social justice. In Bolshevism, that right was given to a progressive class or vanguard party (The Bolsheviks), while in Fascism, a superior nation or race possessed that “natural” right. Similar to the two totalitarian Utopias, Mawdudi viewed his own Islamic party as the vanguard for the Islamic Revolution. He claimed to have been appalled by Europe’s cultural and intellectual trends, yet he was still very much indebted to one particular European construct: Totalitarianism.

However, it should be noted that Mawdudi’s revolution did not entail an armed rebellion or any element of militancy. He, in fact, believed in a smooth socio-cultural transformation that would culminate in an ideal Islamic society. That makes him somewhat different from Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran and Sayyid Qutb of Egypt, both still inspired by Mawdudi’s literature.

He wrote:

“If we really wish to see out Islamic ideals translated into reality, we should not overlook the natural law that all stable changes in the collective life of a people come about gradually. The more sudden a change, the more short-lived it is. For a permanent change it is necessary that it should be free from extreme bias and unbalanced approach”[iii].

This approach appears somewhat similar to Marx’s evolutionary approach to socialism, and his reliance on the laws of historical determinism, through which he predicted (quite falsely) that the economic maturity of capitalism would itself nurture the socialist revolution.

Thus, it is true that most of the Jihadi extremism of the last few decades has been more influenced by Sayyid Qutb and his followers (Ayman-al-Zawahiri, etc.) than Mawdudi. However, he still remains the main ideologue who so coherently presented the Political thought of Islam.

I had Mawdudi’s best-selling exegesis in my house, which was gifted to my grandfather by his friend[iv]. I used to skim through his commentary during the Islamic month of Ramadhan but never gave it much serious attention. The book that I actually read was the one where he probed into the Modern western philosophy and Political themes[v]. At that point, I could not understand much because I was extremely young and unaware of such sophisticated trends.

But I re-read it a couple of months ago just to see whether it was a mere collection of silly conspiracy theories (which are now very prominent in the Islamist circles) or if it did indeed include something accurate. It is, to the best of my knowledge, an accurate understanding of western history and carries no huge deliberate adulteration. He describes certain theological trends within Christianity and then deals with the philosophy that emerged out of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. His texts deal with a wide array of western thinkers, including Descartes, Hume, Locke, Berkeley, Francis Bacon, Kant, and many others. This is why it is no surprise that Mawdudi was so successful in gravitating a large section of young Muslims who had received modern education and were familiar with such modern ideas.

It should be self-evident by now that his intention was not to bring the two continents together; but to set them apart, and to do that, he felt no remorse in borrowing terms and ideas from the ideological repository of the very same people whose influence he sought to expunge from his country.

When he founded Jamaat-e-Islami in 1941, a number of scholars from the traditional clergy initially joined his party. However, many later parted their ways, differing with his overly politicised view of Islam. A very prominent scholar stated that Mawdudi reduced Islam to a mere quest for political power, and thus greatly dented the spiritual and soteriological dimensions of Islam, transforming the religion of Islam into an “ism” hardly distinguishable from other isms, like Nationalism, Fascism, or Communism[vi]. Another scholar noted that in Mawdudi’s Islam, “Theocracy replaces Spirituality as the objective of Qur’anic revelation.” [vii]

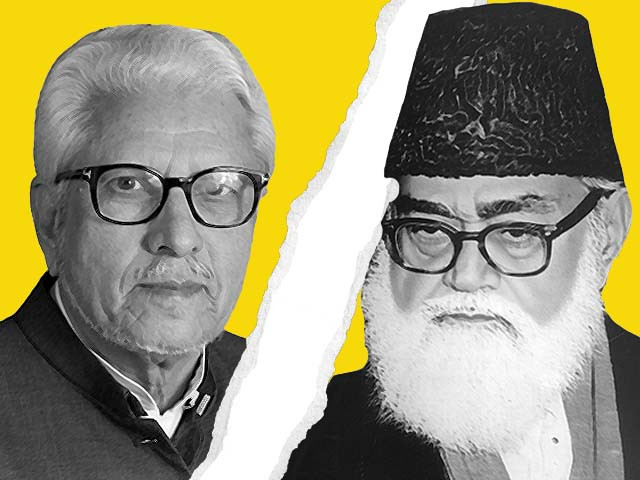

Yet, I believe the most interesting rebuttal to his interpretation of Islam has emerged from the people who once firmly shared his beliefs. Two scholars stand out in this regard: Javed Ahmad Ghamidi from Pakistan and Wahiduddin Khan from India.

Wahiduddin Khan was inspired by Mawdudi’s movement and joined his party, but very soon started to discern deep political connotations in Mawdudi’s exposition of Islam. He felt that Mawdudi, owing to his extensive study of the Western totalitarianism, has brought those external influences in his understanding of the religion. What resulted was a series of correspondence between Khan, Mawdudi, and many of his senior associates, but Khan could not get a convincing enough answer from them. His dissatisfaction culminated in a book entitled “The error of Interpretation,” where he at length elaborated how the Politic-centric worldview of Mawdudi greatly influenced his interpretation of Islam. The contrast between Marx and Mawdudi, which was also used by Wahiduddin Khan in his book, is very pertinent in this case because there does appear to be a glaring similarity. In Marx’s materialist interpretation of history, class struggles became the most important aspect of understanding human cultures. While even some non-Marxists would agree that social struggles and conflicting interests could be important in understanding any human society, many would not go as far as Marx did in implying that law, religion, philosophy, or other elements of the culture have no history of their own, and that their history is merely the history of the relations of production. Khan believed that Mawdudi, indebted to his secular influences, did the same with religion; he took one aspect of the faith, important yet not overriding, and presented the entirety of the faith through that single aspect. In his book, he shows many instances where Mawdudi not simply departed from the established understanding of Islam but tried to convert the faith into a political phenomenon[viii].

Another figure who has followed the same pattern as Khan is Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, the modernist Islamic thinker from Pakistan, who has also provided a sort of antitode to Mawdudi's Political Islam. Though Ghamidi was one of Mawdudi’s very own students, he too began to have an intellectual dispute with the Jamaat’s leadership when he felt that his personal understanding of Islam brought him to entirely different conclusions as Mawdudi.

Ghamidi, apart from agreeing with Wahiduddin Khan’s critique of Mawdudi’s thought, also maintains that in the modern era of Nation-states, there should not be any state religion since nation-states are created on this very premise that all citizens of the state ought to be treated equally irrespective of their religious affiliations. He backs his argument with theological justifications. Though he does not endorse secularism (unlike Khan, who does), he also makes it clear that to have a state religion in Pakistan would be tantamount to suppressing other religious minorities’ rights, which is not permitted in the religion[ix]. This, of course, stands in sharp contrast with Mawdudi’s ideology, which not only rejected the concept of nation-states but also assigned a second-class status to the religious minorities.

So how could the protégés of a radical Islamic thinker become somehow the very opposite? I believe it is due to the fact like every flawed ideology, Islamism too has produced its own internal critics – those who once faithfully adhered to it, then realised the erroneous nature of it and subsequently went on to refute it. Just as there are a number of ex-communists (Leszek Kołakowsk, Ignazio Silone, Wolfgang Leonhard, etc.) who totally discredited the communist ideology, the same appears to have happened with Political Islam. Some of my colleagues who also partake in this discourse often ask me if Political Islam has any future, to which I reply that I do not think that it does; in fact, I feel that it might be in its last stages. Of course, I am no clairvoyant, and I do not claim to give an absolute account of what may happen in the future. But I feel this way because much like Marx, who did not envision his utopian society as a society of Gulags, Mawdudi did not imagine his ideal Islamic society as a constant source of turmoil and infighting.

On the contrary, he believed Islam’s political nature was so appealing that it could convincingly attract the rest of the world suffering from the cultural degradation caused by Liberalism, secularism, and socialism (at least, that is how he viewed it). He was successful in disseminating his political vision of Islam amongst Muslims because it resonated with the Muslim psyche of the twentieth century. That no longer seems to be the case since Islamist manifestations have done extreme damage to Muslims themselves. Just like the global proletariat is no longer awaiting a socialist revolution, knowing that all such previous revolutions only further desecrated their rights, Muslims too are no longer as allured by Islamism as they were once, knowing that it too has only exacerbated turmoil and conflict in their societies.

Perhaps this revelation has happened to some Islamists themselves who, upon realising that their ideology cannot sustain itself without a continuous reliance on bludgeon, went on not just to abandon it but also offer a critical account of their previously held ideology.

In his book, Khan deduces that the Islamist extremism in the world today is a natural corollary of Mawdudi’s interpretation of Islam. I believe he is right in making this assertion because even if Mawdudi himself favored a gradual approach, relying on the “natural law” to take its course, some of his heirs realised that they may have to wait forever if they leave the quest of political Islam to such gradualism. And they appear to have done to Mawdudi’s Political Islam what Communists did to Marxism, that is, to discredit the doctrine of historical determinism, and replace it with a revolutionary will to seize political power. His own party remains committed to constitutional politics but has only become more unpopular with the passage of time.

So what to make of Mawdudi and his deeply politicised Islam? He certainly deserves no credit for creating that. But one can argue that there would be no Ghamidi or Wahiduddin Khan had there been no Mawdudi in the first place. This is because, unlike the traditional clerics, he introduced the trend of studying and examining western thought, which had remained either nonexistent or at least, quite nominal, amongst the Muslim clergy. One can borrow ideas from one world, supplant them with one’s own beliefs, and then use them against that same world. But one can also do that to bring reconciliation between the two worlds. The first creates, Mawdudi, the latter, Ghamidi or Wahiduddin Khan.

This is no anomaly but seems to be a typical historical theme. Intellectuals do not often realise that while castigating one thing, they are actually, unconsciously benefitting it in the long run. After all, who was a more loyal guardian of Church doctrine than Thomas Aquinas in attacking the Averroes’ demands for the full autonomy of secular reason? But in attacking them, he defined specific rules for how secular reason should be separated from faith and established the boundaries of its relative autonomy. With this clear distinction, he exposed Church doctrine to the same danger against which he had sought to defend it.

Or – at the opposite pole within Christianity – who was a more irreconcilable enemy of the idea of involving secular reason in the matters of divine interpretation than John Calvin? But by pitting his profound biblical conservatism against scholasticism, he destroyed trust in the continuity of the Church as a source of interpretation of the doctrine. For the task of interpretation, he left to future generations only the very secular reason he so vigorously had condemned. In fact, he unconsciously contributed to the creation of an intellectual environment that soon nurtured the advocates of natural religion and the deists[x].

Similarly, Mawdudi, with his deep probing into the western thought, started a process that led to the opposite of what he actually intended; some of his own acolytes ended up reconciling East and West.

[i] Abul Ala Maududi: An existentialist history

[ii] The writer mentioned here is Mahirul Qadri: Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, P#33.

[iii] Sayyid Abul A’la Mawdudi, Islamic Law and Constitution, P#48.

[iv] “Tafheem-ul-Quran”, a six volume translation and commentary of the Qur’an.

[v] “Tanqeehat”, a collection of Essays that Mawdudi wrote during the 1930’s, first published in 1939.

[vi] Maulana Manzur Nu’mani, a scholar of Deoband School of thought: Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, P#114.

[vii] Abu’l-Hasan Ali Nadwi: Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, P#62.

[viii] “Taabir Ki Ghalti”(The error of Interpretation) by Maulana Wahiduddin Khan: A synopsis of Khan’s critique can be read here, The Political Interpretation of Islam - Dr Khalid Zaheer.

[ix] Islam and the State: A Counter Narrative( Javed Ahmad Ghamidi), State and Government - Javed Ahmad Ghamidi.

[x] The Polish Philosopher, Leszek Kołakowski, wonderfully explores this irony of intellectuals in his book, “Modernity on Endless Trial”.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ