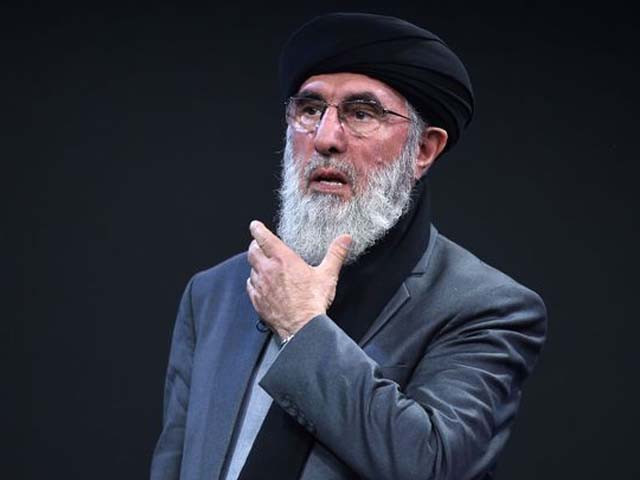

As the withdrawal of the American forces from Afghanistan appears imminent, Afghan politicians are forging new alliances to climb up the power ladder. In this regard, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s recent high-level visit to Pakistan was a major development. The former premier of Afghanistan acknowledged Islamabad’s role in the Afghan peace process and condemned India for politically meddling in Afghan politics. Hekmatyar, however, is widely remembered as a warlord and the vivid memories of his actions in Kabul during the Afghan conflict raise questions about his political integrity. Apparently, his visit reflects the notion that he is looking for political favours in the neighboring capital. Therefore, should Islamabad consider extending a diplomatic hand to Hekmatyar to contain India’s rising influence in Kabul or should the state avoid risking relations with the incumbent Afghan government?

Hekmatyar’s relationship with Pakistan goes back to the 1970s. He first visited the country when he was exiled by the Doud Khan’s government during a crackdown on the Muslim Youth Organisation in Kabul. In 1973, he received initial military training in Pakistan and developed a close association with the Pakistan army and military intelligence. Concurrently, his charismatic persona and popularity among the Afghan Mujahideen drew him closer to the ideologues in Islamabad, and he was widely favoured by the intelligence quarters as a potent and formidable opponent to the communist forces in Afghanistan.

After the Soviet invasion in 1979, Hekmatyar’s Hizeb-e-Islami received massive funding from the American CIA and Saudi intelligence through Pakistani channels for mobilising rebel groups. In the 1990s when the Afghan government under Mohammad Najibullah lost its hold, his forces tried to capture Kabul. He was, however, confronted by the Tajik forces led by Ahmad Shah Masood and Abdul Rashid Dostum, and their conflict later culminated in a civil war. Hekmatyar’s forces launched scores of rocket attacks directed towards Kabul, which is why he is infamously known as “the butcher of Kabul” in Afghanistan.

In October 1996 when the Taliban forces captured Kabul to reestablish the so-called “law and order”, Hekmatyar and his allies were forced out of Afghanistan. He remained in exile throughout the post 9/11 period and returned to his homeland in 2017 after a ‘peace deal’ with the incumbent Ashraf Ghani’s government. His return, however, was a divisive movement in Kabul’s politics. As The Guardian reported in May 2017, his return brought back the memories of the 1990s when thousands of people died because of the confrontation between Hekmatyar and Masood’s forces.

Contempt for Hekmatyar’s return to Afghan politics is especially prevalent among the Afghan youth. They believe that if back in power, he will align himself with the Afghan Taliban and will try to reestablish a rigid adherence to the Shariah. Thus, it is likely that if Islamabad endorses Hekmatyar, the move will possibly alienate the already polarised Afghan youth against Pakistan. Furthermore, it can also push them closer to New Delhi’s rising influence in Afghanistan, as the former ostensibly supports the so-called ‘moderate’ factions of Afghan politics.

Apart from that, his state-level protocol in Pakistan also drew criticism from some political factions within Pakistan. Recalling the Taliban atrocities, politicians from the opposition parties and members of the Pakistan Democratic Alliance (PDM) alliance, staunchly criticised the government for Hekmatyar’s high-level treatment in Pakistan. Since the opposition’s MNAs and their parties enjoy special influence among the youth of the tribal districts of Pakistan, they can possibly exploit the situation to gain political support during the upcoming anti-government agitations.

Moreover, Hekmatyar is also accused of suppressing the Iran backed Shia minority in Afghanistan – something he often refutes. However, his recent support for implementing the majority’s version of Islam, and his disdain for Iran, which was also expressed while speaking at the Institute of Policy Studies at Islamabad, can land our ruling-elite in hot waters. His unconstrained expression of such views on Pakistani soil can thwart recent efforts to restore brotherly relations with Tehran, and can also add fuel to the already exacerbating Shia-Sunni divide. Opposition members and critics of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government already accuse them of having a ‘soft-corner’ for the hardliners, and such steps by Islamabad will likely strengthen such views, both nationally and internationally.

Lastly, supporting Hekmatyar’s Hizb-e-Islami was a compromise America made during the heyday of the Afghan jihad. Steve Coll, in his path-breaking account of the Afghan conflict, Ghost Wars, highlights that while the CIA liaisons in Pakistan favored Hekmatyar, Ahmad Shah Massod, the so-called moderate leader of Tajik rebel forces, was a widely preferred option within the American diplomatic circles. The latter largely dominated the post 9/11 American foreign policy and are highly influential within the American civil establishment. Hence, any attempt by Islamabad to assert itself in Afghan politics can elicit an American reaction, especially when the recent Washington-New Delhi diplomatic romance is at its apex.

Thus, while advocating for a peaceful end to the Afghan conundrum through dialogue, Islamabad should also try to maintain a diplomatic balance between the US-backed Ghani government and the opposing Hekmatyar and his allies. Tilting more towards the latter can potentially alienate many regional and international powers, which is a risk Pakistan should avoid. In the past couple of years, not only have we been successful in maintaining such a balance, but our stance has also been widely lauded by global powers like America and China. Sustaining such diplomacy, therefore, is imperative to avoid conflicts with already hostile neighbours.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ