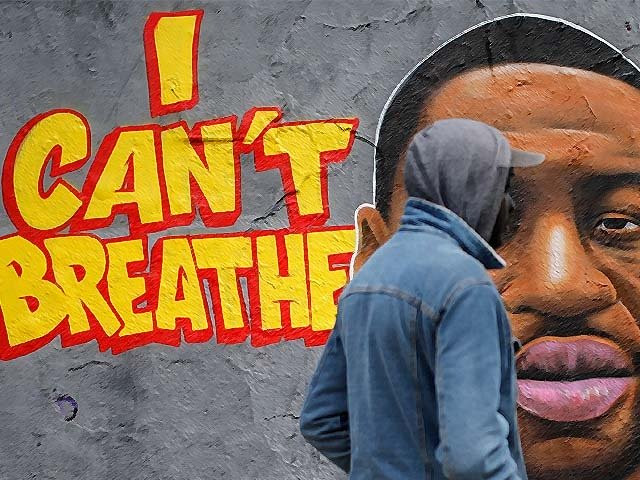

We have recently seen an atrocious death by the knee in America, which has led to many gathering and chanting “I can’t breathe” in the United States, signifying the struggle of Black communities. The killings of Ahmaud Arbery on February 23, 2020 and George Floyd on May 25, 2020 emanate from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, put together at a time where one in five black Americans were slaves.

The convention prohibited Congress from abolishing the law on importing slaves into America for 20 years, and also required all states to return fugitives to their owners. At the time of the convention, for the purpose of determining each State’s representation and its electoral votes for president, only three out of five slaves would be counted under the classification of ‘other persons’ or those ‘held to service or labour’. Even half a century later, in 1837, the Convention still differentiated between ‘men who could vote’ and ‘men who could not vote’.

New York’s law of emancipation from slavery was also a farce; as it did not free any living slave from their owner, but merely provided liberty to a child born to a slave mother after he or she had served the mother’s master until adulthood, as compensation for the owner’s future loss of property rights over the slave-child.

The deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd and many others revive the constitutional and social struggle, which was personified by William Lloyd Garrison on July 4, 1854, when he set ablaze the fugitive-slave law of 1850 along with the decision of the Federal Tribunal of Boston ordering Anthony Burns, a fugitive from slavery, to be returned to his Virginia Owner. William termed the US Constitution “the parent of all other atrocities” and “a covenant with death, an agreement with hell” and set it ablaze as well.

While civil unrest spreads in the United States, attempts to curtail the virus of racism are underway, in the form of aggressive media coverage, human rights lobbying, protests outside the White House and an overall outcry by politicians, celebrities and public figures about an unwritten, unconstitutional disparity that exists in society even today despite laws being changed.

It is heartening to see until you realise that unfortunately, Pakistan is also home to a disparity that runs through the very fabric of the country, one that is based more on class than skin colour and one that may not be written constitutionally but promotes a form of slavery nonetheless. I am referring here to cases like those of young Zohra, who lost her life because she released her employer's parrots or the case of Sakina who languishes in jail for almost six years for a crime that was definitely not hers.

Sakina Ramzan is a 70-year-old woman who was carrying electronic items on the behest of her employer when she was intercepted at the provincial border between Balochistan and Sindh. The items marked for the relatives of the employer, were searched and were found to contain over 10kgs of narcotics.

Section 7 (iii) of the Control of Narcotic Substances Act 1997 provides that the transportation of drugs within Pakistan will result in a statutory punishment of life under Section 9 for drug offences in excess of 10kg. The law, however, is culturally silent. Neither does it consider the inability of an employee or house help to challenge the employer, nor does it hold the employer vicariously liable, and accordingly culpability falls on those pressurised into situations such as Sakina’s.

The trial court convicted Sakina with a life-sentence for transporting drugs in 2014, while the high court rejected her appeal and she remains incarcerated ever since. However there was a new beacon of hope for her in March 2020. The Supreme Court of Pakistan took up her case and granted her appeal while issuing notices to the relevant authorities.

Sakina’s case was to be listed at the end of March, however, before any action could be taken, the pandemic limited the listing schedules of courtrooms across the country also delaying the date of her hearing. While the message that emanates as a result of constitutional crisis identified by William Lloyd Harrison spreads (as does the virus), justice for Sakina seems to have fallen prey to the pandemic.

On the one hand Ahmed and George are no more, but they are immortalised through their cause, which seems to be thriving despite the pandemic while here at home in Pakistan Sakina is alive, but her struggle for justice goes unnoticed especially since her social class much like the skin colour of some is not considered worthy.

Remnants of slavery are everywhere - including Pakistan

Sakina is alive but her struggle for justice goes unnoticed especially since her social class is not considered worthy

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ