This is the second part of a two part series. Read part one here.

~

On September 7, 1974, Pakistan’s parliament by an overwhelming majority passed what is known as the second amendment stripping Ahmadis off their Muslim status and declaring them to be non-Muslims for “legal and constitutional purposes”. This move was and to this date remains unprecedented as Pakistan remains the only country to do so. But why did it happen? Once again, the matter was politicised by the religious right, but the state response was different. The immediate stimulus for the agitation came from a skirmish between Ahmadis and some medical students at Rabwah railway station.

Once the news broke out, the religious right was able to frame it as rebellion by Ahmadis against the state, thus starting their violent agitation to compel the state to declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims. Just like in 1953, the agitation was extremely violent resulting in damage to Ahmadi properties and even loss of lives.

Initially the state tried to curb it through force and in fact it was able to control the situation in one week. However, later on the then prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto decided to take the matter to the parliament where his own party had absolute majority and which voted Ahmadis as non-Muslims. Why did Bhutto do that?

There were several reasons. At a more tactical level, Bhutto, since the matter was already getting politicised, wanted to take advantage by outflanking the religious right. Punjab was his base and he did not want to cede any political space to them. In fact after passing of the second amendment, he boasted in big rallies that he had finally solved a 90-year-old problem.

Secondly it is claimed by some quarters that to a certain extent there was also some pressure from Gulf States particularly Saudi Arabia and King Faisal, who did not want Ahmadis to come for Hajj. But at a broader and contextual level, there was another reason: break up of Pakistan in 1971.

Given that East Pakistan had separated due to ethnic grievances, the questions about identity and nation building resurfaced. Since Pakistan’s remaining wing was also ethnically diverse, the chief concern was to build civic nationalism and national identity in such a way that further fragmentation on ethnic lines could be avoided. The state chose to cultivate a more religion-based identity as Islam was a common factor amongst all the major ethnicities in Pakistan.

The 1973 Constitution made Islam a state religion and also contained explicit clauses stipulating that both president and prime minister were to be Muslims. Since the constitution envisioned an Islamic direction for the country this automatically elevated religious issues, of which the Ahamdi issue was a major one, in the public discourse and also put pressure on the state to define a 'Muslim' accordingly. In fact, religious groups that were demanding that Ahmadis be declared non-Muslim were also anchoring it in the 1973 constitution and its Islamic provisions.

When parliament was debating the issue, a campaign in the media was ongoing that not only called Ahmadis non-Muslims but also labelled them as traitors by constantly referring to their founder’s alleged links to the British. Moreover, the Bhutto government had also constituted a high court tribunal to investigate rioting and its proceedings were sensationalised and reported by the press daily.

In the wider public imagination the image of Ahmadis was morphing into a combination of being both heretics and traitors, an image which continues to this day as evident by recent twitter trends like “ #قادیانی_اقلیت_نہیں_غدار” and “ #قادیانی_دنیا_کا_بدترین_کافر”

Once Bhutto decided to take the issue to the parliament, under such an environment, there was only going to be one outcome. One justification of the second amendment given by its supporters was that it would “protect” Ahmadis once they had been declared non-Muslim, the religious right would not be able to target them again. However, this is not what has happened since then. The amendment, instead of protecting Ahmadis became the blueprint for introduction of further regressive laws targeting their religious freedom. The religious right then started to demand that since Ahmadis, despite being declared to be non-Muslims, were still acting like Muslims, further preventive legislation was needed.

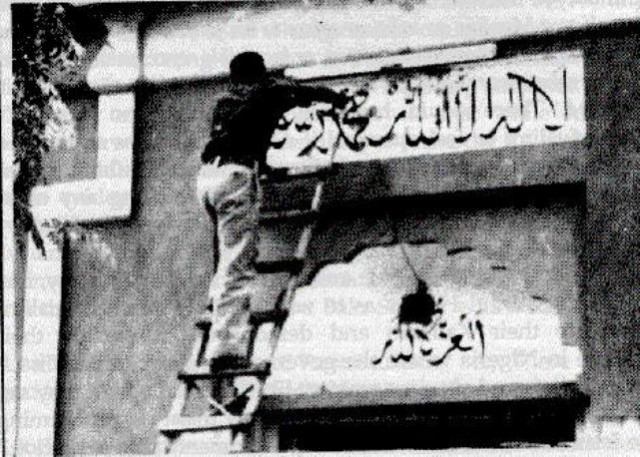

Pakistan witnessed intense Islamisation under general Ziaul Haq, who wanted to legitimise his rule and therefore provided a conducive environment for the religious right to press this demand more potently. In 1984, a group of religious leaders issued an ultimatum to Zia to take more measures against Ahmadis. In response, the Zia's regime promulgated an ordinance which severely restricted Ahmadis’ right to practice their faith and prohibited them from ‘posing as Muslims’ by using Islamic symbols and nomenclature in describing their religion or places of worship.

That ordinance, in effect meant that the state after excluding Ahmadis was now criminalising and persecuting them. Furthermore, these laws gave the religious right further impetus to spew more venom against Ahmadis. The attacks on their worship places increased as mobs also developed a certain sense of entitlement to take the law into their own hands. In 1993, the Supreme Court of Pakistan also upheld Zia’s ordinances thus further cementing the prosecuted status of Ahmadis.

In recent times, due to the situation constantly being politicised, by literally all major political players, and I mean all, things have taken an even more ominous turn, as now there are demands of also stripping Ahmadis from the little to no rights they are given as one of the minorities of Pakistan. They are literally being categorised as a “different” type of minority which cannot be afforded even basic citizenship rights. As eloquently pointed out by Ali Usman Qasmi,

“Now the demand is to declare them murtads. The way Pakistan’s legal language has evolved, Ahmadis have merely been reduced to blasphemers and traitors which means their existence in the country is under threat. To quote Hannah Arend, Ahmadis in Pakistan do not have rights to have rights.”

Academic Sadia Saeed has identified three state responses, each one harsher than the previous, over the Ahmadi issue. First was accommodation, when in 1953 the state curbed anti-Ahmadi agitation, second was exclusion, when the state declared them non-Muslims in 1974 and the third was criminalisation under the Zia regime, where anti-Ahmadi ordinances were introduced. The way we are regressing, I am afraid that a fourth one is not far away; ethnic cleansing or forced displacement of Ahmadis from Pakistan.

At the end, I will say only one thing, one can vehemently disagree with Ahmadi beliefs and firmly believe what one likes about them, without hating or persecuting them. May we all be blessed with empathy, which is the greatest human virtue.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ