This is the first part of a two part series. Read part two here.

~

Although Pakistan is no heaven for any minority, religious or otherwise, the discrimination and bigotry against Ahmadis is staggering. Despite the fact, that they have already been declared non-Muslims through the second amendment in the constitution, and are extremely marginalised, the hatred against them keeps growing. In fact, to even defend them on humanitarian grounds is extremely difficult and becoming more so. Moreover, in recent times, literally all political parties, even those with secular leanings, have tried to weaponise anti-Ahmadi sentiment for gaining political mileage.

We, as a society have entered a vicious cycle where the opposition tries to pressurise the government by saying they have a “soft corner” for Ahmadis and the government “defends” itself by expressing virulent hatred against them. In the process, a community, which is peaceful, keeps a low profile, is already marginalised, gets even more cornered. There are already some quarters who are openly calling for Ahmadis to be declared as blasphemers and traitors while demanding capital punishment for them.

This merits the question: Why and how we have come to this stage where hatred for the Ahmadis has become a part of our collective national psyche? There is a tendency to believe that Ahmadis are hated due to their religious differences with Muslims. However, this in my opinion, explains a very small, if any, part of the puzzle. Substantial differences exist between various sects and while these differences have at times manifested in violence, it was often carried out by fringe groups. In the case of the Ahmadi community, it is the collective mainstreaming and rationalising of hate, at times under the active tutelage of the governments in power.

The answer, in my opinion, does not lie in religious differences but in politicisation of these differences and the way the state has responded to such efforts over time. State’s response, as we will see, has changed from being accommodating of Ahmadis to their exclusion and then even their outright criminalisation. The second main reason is the way the state has tried to cultivate a national identity by infusing religion in the polity, particularly after the East Pakistan debacle. As damaging as each was on its own, its it’s the interaction between the both that has led to the present situation for the Ahmadis.

One has to keep in mind that they are a relatively new sect, which makes them more vulnerable. When the Pakistan movement was unfolding, within the Muslim community, the chief opposition actually came from religious groups like the Jamaat-e-Islami. The party was professedly opposed to the creation of Pakistan and so were the Ahrar another dominant religious group active at that time. However, despite their opposition to the idea of Pakistan and Mohammad Ali Jinnah (who was even called Kafir-Azam by Ahrar leaders such as Maulana Mazhar Ali Azhar), the country still came into being.

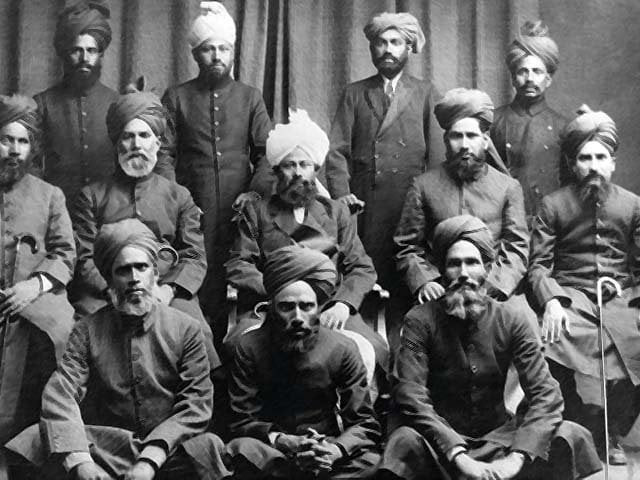

Compared to these groups, Ahmadis supported Jinnah and also played an active role in the Pakistan movement. During the struggle for independence, at one stage Jinnah was asked about the status of Ahmadis to which he replied

“Who am I to declare a person non-Muslim who calls himself a Muslim?”

According to several accounts, Jinnah invited the Ahmadi leadership to migrate to Pakistan at the time of the partition and assured them of the protection of their rights as the citizens of the country. After taking over the post of governor general, Jinnah appointed Sir Zafarullah, an Ahmadi, to the post of foreign minister, clearly indicating that the founder of Pakistan considered a person’s faith their personal matter.

The Ahrar first raised the demand to declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims in 1949, just a few weeks after the Objective Resolution was passed, which laid out the blueprint for the country’s future constitutional and legal framework. The resolution, while professing to safeguard the rights of minorities, used religious terminology and made it clear that the future direction that Pakistan would take will be based on religion. As academic Sadia Saeed, points out

“The allegiance of the state to Islam at this crucial moment gave the Ahrar leadership impetus to make their anti-Ahmadiyya demands public.”

The decision to politicise the issue by Ahrar had less to do with religion but more to do with gaining political traction as they felt irrelevant. Their demand was declined by the state in 1949 but they continued to whip up hatred against Ahmadis and were joined by other religious parties, particularly, Jamaat-e-Islami who like Ahrar felt irrelevant and marginalised in Pakistan. Ironically, both these groups, had opposed the creation of the very country they now found themselves increasingly politically irrelevant in.

Then in 1953, Punjab saw the most unrest since partition as Ahrar and their allies were able to rouse public sentiments against the Ahmadis. The agitation was in some part supported by the then Punjab chief minister to undermine the then federal government under Khawaja Nazimuddin. Emboldened by that, the Ahrar issued an ultimatum to the central government to declare Ahmadis non-Muslim and to remove them from all key posts. However, the government stood its ground and ordered the arrest of some of the party's key leaders. Following the arrests, riots broke out and the city of Lahore had to be briefly placed under martial law.

Subsequently, a two-member inquiry committee consisting of then chief justice of Pakistan Mohammad Munir and Punjab High Court judge Rustam Kayani was formed, which published its report in 1954. The report blamed Ahrar, other religious outfits like the Jamaat-e-Islami and the then Punjab government for deliberately stoking up the violence.

Since the key demand from the agitators was the declaration of Ahmadis as non-Muslims, the report concluded that it was futile for any government to define someone as a Muslim, as there was actually no unanimous definition and the clergy also differed a lot among themselves. The report upheld the importance of equal and full citizenship rights for people belonging to all the faiths.

At that time, the leadership of newly created Pakistan did not buckle under pressure and took firm action to protect its Ahmadi citizens. The decisive action by the state showed that although there would always be agitators willing to arouse and exploit sentiments, but a decisive and apt response from the state (whose raison d'etre is and should be the protection of its individual citizens) could nullify such efforts.

The anti-Ahmadi movement lost its steam and the issue became dormant for the next 20 years only to resurface again in 1974. Only this time, even though the issue was politicised again, it unfolded in very different ways, leading to drastically different consequences.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ