When Ukhano (Umar Khan) was exposed for alleged harassment recently by multiple women, he was instantly 'cancelled' by a significant percentage of people on social media, that is until Polish vlogger Eva Zu Beck shared her experience of working with him.

Just because he hasn't harassed you, doesn’t mean he’s not a harasser

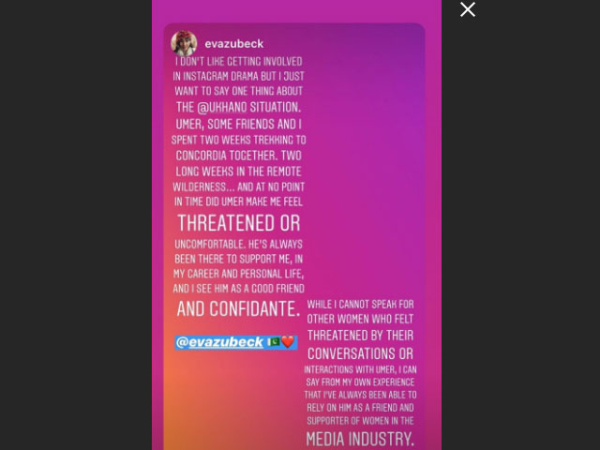

In an Instagram story, Beck shared how she went trekking with Khan for two months, during which he never made her feel uncomfortable or threatened at any point. It made sense for her to come out in support of her friend. But here's the bigger argument. How can Beck, a foreign traveller with a strong following on social media, relate to – dare I say – 'random' girls like you and I? Beck's personal experience of working with Khan undermines and disregards the testimonies of a dozen other women.

Anoushey Ashraf, in a now deleted post, also initially extended support to Khan. But once presented with the evidence against him, Ashraf retracted her statement and shared that she had no idea about it. Again, this support was really bizarre because just because he's your friend, doesn't mean he can't be a harasser. Blindly supporting your friends, until you've been presented with solid, credible proof and have little choice left, undermines the victims who speak out about their experiences with the said person.

Obsession with proof

Last week, when actor Mohsin Abbas Haider was outed as an abuser by his wife Fatema Sohail, it started a vigorous debate on domestic violence in Pakistan. Numerous celebrities came out in support of Fatema, and condemned the actor's behaviour. Some actors even claimed to witness Fatema's ordeals.

https://twitter.com/realhaniahehe/status/1152692472419627008

https://www.instagram.com/p/B0LKqlSgrSC/?utm_source=ig_embed

The case of Mohsin and Fatema had a very one-sided opinion from people. Mohsin was labelled an abuser on social media and was rightfully called out for his problematic behaviour. He was eventually fired from a very famous prime-time show. However, people are still having a hard time calling Ukhano out on his troublesome activities.

What’s the difference in their cases apart from the form of harassment/abuse? Proof. Our society is obsessed with physical, tangible proof of harassment or abuse. Since the possibility of the screenshots being forged weakened the proof many girls had against Ukhano, the public reaction to his event wasn’t outrageous. But Fatema's bruised pictures quelled our thirst for solid evidence and that explains the immense public outrage at it.

The benefit of the doubt

In Mohsin's case, a few social media users lashed out at Fatema's supporters to 'wait for the other side of the story'. This clearly implies that the proof and pictures Fatema shared on social media to account for her ordeal weren't enough. In Ukhano's case, the screenshots women presented were easily disregarded on grounds of being fake or doctored. As if whatever the vlogger himself said was definitely true.

In Ukhano's case, Taimoor Salahuddin, more commonly known as Mooroo, shared that he would rather wait for both sides of the story than jumping onto a bandwagon of 'outrage culture'.

He uploaded an Instagram video stating,

"We don't know the truth for now. We need to weigh in facts and wait for the truth to come out. What does this 'cancel Ukhano, cancel everyone' even mean? This outrage culture on social media needs to be heeded at. Now that we know one of side of the story, let’s wait for the other part. I’m not saying I believe Umar. I’m just saying I support the truth – whatever that might be.”

It's extremely disappointing, really. How men in our society are always given the benefit of the doubt and a chance to 'explain' or 'excuse' themselves. They are not only granted the right to justify but also significant forums and platforms to speak up on – case in point: the press conference Mohsin was able to arrange right after the evidence against him went viral. Not only do women have lesser access to exposure, they are also always going to be doubted. Regardless of the evidence and ordeal they share, they would always be questioned. They would still have to prove themselves to be worthy enough to be believed.

How to hold the accused accountable?

One of the biggest controversies this year has, no doubt, been the Lux Style Awards ire. When the nominations of the 18th edition of the famous awards came out, it left the fraternity and others baffled to see the Ali Zafar's name in the nominations for the Best Actor category. What baffled everyone even further was when he won the award despite so many nominees rejecting their nominations.

When Junaid Akram was exposed for alleged sexual harassment by multiple women last year, I, for one, was sure how his career was almost over given the plethora of evidence. But boy was I wrong. He's still out there, making videos and being invited to various forums as a guest. When Kevin Spacey was exposed for the same crime, he was playing a lead in one of the biggest shows of the time, House of Cards, on Netflix and was 'cancelled' when the allegations surfaced and even before the matter went to court.

Which leaves one wondering, would the accused ever be liable for his actions? The accusations against big names in Pakistan might only tarnish the public image of the accused for a while but would never completely destroy it. And that is the most problematic aspect.

Internalised misogyny

Khaled Hosseini once said,

"Like a compass needle that points north, a man's accusing finger always finds a woman. Always."

And it has been relevant ever since. The patriarchy has induced in us feelings of misogyny to such an extent that it has become almost a reflex action to hate the woman in every case. Whether it’s putting the blame on Meesha Shafi or on the ton of women in Ukhano’s case, the society will always look for the closest woman to put the blame on.

The most tragic example of this was Mohsin's case, because despite having physical proof we have always craved for, the accusing finger was still pointed at either Fatema or Nazish, Haider’s second reported partner. Some blamed Fatema for ‘putting up with the abuse for so long,’ completely dismissing the emotional, mental and financial stability required to separate from your partner. While some blamed Nazish for being the home-wrecker which, albeit true, is the most insignificant part of the issue and diverts attention from holding the man accountable. If anything, this is taking the man out of the equation, and pitting one woman against another.

Method to madness

We know there's National Response Centre for cyber crime where one can go and report their complaints. But how efficient are these centers? In order to cater the huge number of similar cases, which we know is too many to count, there should be a separate harassment cell. This particular section should only deal with #MeToo and #TimesUp cases.

Then comes the part where the complaint is officially filed. Once an accuser has made their ordeal public, the legal proceedings should begin to handle the case. For organisations, it is imperative to conduct an internal or private investigation on the matter. And until proven innocent in the court of law or under private investigation, they should disassociate themselves with the said person.

From what I’ve gathered after reading, writing on and discussing harassment in Pakistan with multiple people, it’s obvious that there’s hardly any hope for the victims.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ