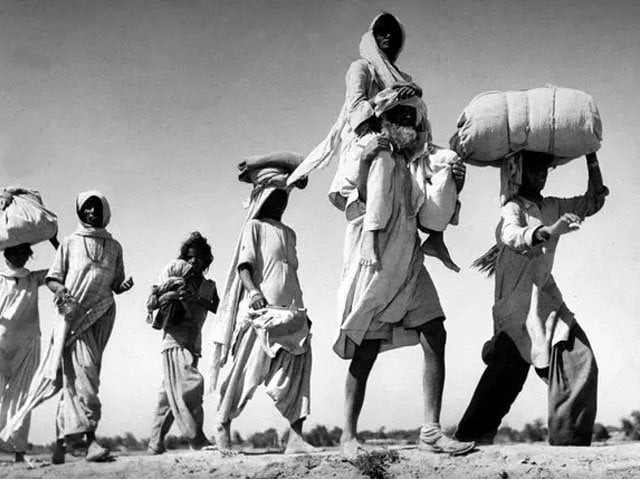

As boundaries were rashly drawn by the British and their colonial country was left ravaged by war, how aware were these higher orders that communities, families and friendships would be so ruthlessly ripped apart?

Everyone from both sides of the border have their own tales of Partition. My own daadi and naani (paternal and maternal grandmother respectively) often narrate their accounts of pre-Partition India, Partition, and post-Partition Pakistan. They recall their house, Karamat Manzil in Dibaii (undivided India), and tell us about the mansion-sized havelis that they, and everyone they knew, lived in. There are endless stories about friendships that seem to be etched in their memories. They tell us about good-natured neighbours who visited each other's homes and shared snacks from roadside vendors. From innocent childhoods to naive adolescence and eventual adulthood, these people shared both good and bad times – regardless of their faith, caste, colour or creed. To quote an elderly gentleman from work,

“Before Partition we were like one family; Muslim, Sikh and Hindu. Nobody ever thought there would be a partition. My mind is still confused why people changed so quickly.”

And then came 1947. My aunt told us about how the girls of the house would be asked to hide after dark to be camouflaged from any unsolicited attention and hence danger. Both my daadi and naani lost a brother in the ensuing disturbances; he was due to appear for an exam and never came back home thereafter. My daadi told us about the train ride from Dilli (New Dehli) to Lahore and the immeasurable terror she carried in her heart throughout the trip. May be it was the obvious danger she was all too aware of, maybe she was scared for the children who accompanied her, or perhaps it was a fear of the unknown: what, who, where, how, and most importantly, why?

There are stories of refugee camps — overcrowded and overrun with disease. There are accounts of youngsters who jumped over dead bodies to get to school. There must be other events that people may have experienced or known about but don’t have the heart to share, in the fear of reliving the anguish. A friend’s aunt goes mute when others recall the horrors that she is trying hard to forget till today.

Today I recall the 'Suitcase of Memories' from Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy’s Home 1947 exhibition. This section consisted of several suitcases that contained belongings of people who had fled in a hurry — their only aim being avoiding the riots and rioters. The suitcases said a lot about the lack of thought given while figuring out what to carry when escaping the impending threat of ruthless insurgents. They showed just how unprepared and unwilling these people were to leave behind their homes and belongings.

https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=346830252451677&id=202204976914206

However, for a great number of people, it was more than just their physical belongings that they were leaving behind. For some, it was a sibling staying back to protect their family’s assets. For some, it was a brother who got separated in mob violence. I’m sure there is one question that many splintered families have asked since 1947: could they possibly be alive?

This reminds me of a story my cousin shared about a retired army major who, to date, is lovingly called Captain Uncle. Captain Uncle was serving in the British Indian Army near Pune, miles from Punjab where his family lived at the time — his father, wife and two children. While he was at the border, his family of four died. Nobody knew exactly what had happened to them. But according to the common narrative of the time, it was likely that the son was slaughtered alongside his grandfather, and that the wife joined thousands of Indian women who jumped into the village well to avoid being raped, murdered or abducted. Captain Uncle was unaware of any of this and, following the instructions decreed by the army, he moved to Lahore in the newly created Pakistan.

Post-Partition, the borders between India and Pakistan were loosely open and movement between the two countries was relatively easy compared to the situation today. To understand what fate his family had met, Captain Uncle would regularly travel to the Wagah Border, cross Amritsar through the Attari railway station and then take a train ride to interior Punjab (on the Indian side). Several inter-border trips later, Captain Uncle met an old acquaintance still based in the same village.

And that is when he was told of the horrors his family had met. The story he learned was painful, and far more brutal than he’d probably imagined. The village where the family lived was predominantly Muslim, and when Partition was decreed, the neighbouring Sikhs and Hindus attacked these Muslim residents. When the rebellion broke out, 1,500 Sikhs and Hindus barricaded the locality, maintained a three-day stand-off, and eventually killed any and every one in sight. I would like to believe that Captain Uncle eventually consigned his family’s history to the past – where he now, hopefully, aims to keep it buried.

We know that the migration was massive. Historians claim that the 1947 Partition was history’s greatest and bloodiest mass movement of people. Until they reached their respective destinations, I doubt anyone believed that they would make it alive. Let’s talk about those who wanted to leave but couldn’t or didn’t — for whatever reason: age, ill health, insecurity, denial. Did they survive? What were their stories? Either way, everyone had to forge a new life.

I am sure endless families across India and Pakistan experienced these brutalities. Sadly though, these generations are fading away, and we cannot allow ourselves to sensationalise that era. While August 14th can be commemorated and celebrated as the birth date of Pakistan, the atrocities committed during the period should also be remembered. Let us not forget the struggle because only by understanding the element of people involved, we can comprehend the element of sacrifice involved. And while we are at it, let’s give a thought to what they left behind and how their worlds suddenly changed, never to be the same again.

Happy Independence Day, Pakistan!

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ