She said “core”. Not “choir” but “core”. The person she said it to was perplexed for a minute, before it dawned on them that the word “choir” had been mangled. As the story made the rounds in school, for a little while, everyone listened, chuckled and was amused by the girl who said core not choir.

It was an easy enough mistake to make in a country where English is not a first language for many. It was cruel and mean-spirited to make fun of that girl. Some people would argue that they were just school kids. But would you have had the same reaction if she had mangled a word of Urdu? Would you have found it mean and cruel, or would you have been dismissive, been under the impression that it served her right, that she should have known how to pronounce her national language?

I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to why people react differently to Urdu and English. For a while, I believed the usual complaints of the crowd, that Urdu was dying out, that English was a sign of upward mobility, that provincial languages should be given more importance. Some people welcome the change: people like to give examples about how Urdu is a forced language. And then there is the classic, ‘Look what happened when we threw Urdu at East Pakistan’ argument.

I welcomed the change, came to a conclusion that kids now mix and match Urdu and English as they please, a curious Minglish, if you like. Aren’t languages living entities that are subject to change? And then, some people can’t bear that change. Purists argue the death of a poetic language, dismiss Minglish as fad of this generation only. Whatever will become of Urdu, they moan.

But I have something to say to all the naysayers, to all the people who would take the example of the choir girl and use it to say, “Look. This is what English-speaking children of Pakistan are like.” I say, dream on. Urdu isn’t going anywhere. Neither is English. It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it. It’s about the stigma of mangling your words and not being able to speak a language properly, whether it is English, Urdu or Swahili. And here, in Pakistan, perfection in a language is demanded.

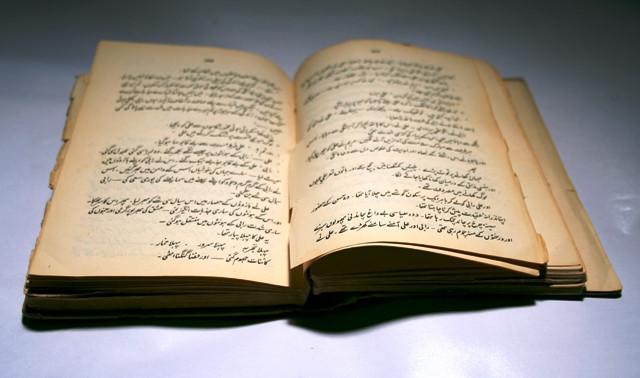

The first time I opened an Urdu book I was nine years old. I had never lived in Pakistan before that age, and so while I could speak Urdu, I couldn’t write or read it. Noon ghunnas, do chashmay hay, and jeems danced before my eyes. The boy next to me in class could read Iqbal’ s poems, I had trouble between seen and swaad.

This wasn’t that much of an issue - I got through Urdu and people around me seemed more concerned with the A in English, in any case. But never, not even when at 16 I bid farewell to academic Urdu in my last exam of the subject, did I for once underestimate Urdu. Not for once did anyone in my class think it was all right to be “bad” at Urdu. Any boy or girl who passed comments like that was not ostracised but a certain amount of disrespect was handed to them, even in Class 4.

Around us, adults raged conversations, pitied the state of Urdu education, wondered whether to curtail English. Among the kids though, the one who participated in Urdu elocutions and bagged the Bait-Baazi trophy, it was all that more special and appreciated.

This is not a competition between English and Urdu - the English debater is just as praised as the Urdu poet. I mean that young adults value someone who can speak a language well. For some reason, we look towards people who can speak well, whose fluency isn't bogged down by questions of identity and complexes and education. As childish as making fun of choir girl is, the people who did it would do the exact same thing if she had mangled an Urdu word. They would do it because they’ve been taught that the only way to speak a language is the correct way. These are the kids who have no biased attitudes to languages, because they aren't as self conscious as their parents. By the time they turn 18, they’re already fluent in both, or becoming fluent. They don’t invest emotion into a language: they treat it as it is, something to be spoken correctly. And that makes all the difference.

Speaking imperfectly among the perfect

Not once did anyone in my class think it was all right to be “bad” at Urdu - Urdu is very much here to stay.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ