Is reformation of Pakistan’s civil service another empty promise?

“How would you reform the civil service?”

Some eight months ago, when one of the members of the interview panel constituted to select the most suitable candidates for the Central Superior Services (CSS) asked me this question, I heaved a sigh of relief. The questions prior to this were trickier than my expectations, and hence unnerving. But this one was, in cricketing terms, a half volley, and I had to try to make the most of it.

However, less than a minute into my impassioned speech on what I believed blighted our esteemed civil service and what ought to be done to improve service delivery, the interviewer had lost all interest. Perhaps she was sick of the entire civil service reforms debate and wanted to hear something unhackneyed. Of that ilk I had little to offer.

In hindsight – and, lest I forget, the absence of five veteran faces looking me in the eye – I think there is little else that I could have said. In fact, there is no possible dimension of this question that has been left unexplored, and perhaps the only proposal that might sound fresh and novel in the circumstances would be to do away with the system of a centralised civil service altogether.

Although, given everybody’s frustration with the existing system and the sheer number of commissions formed to propose reforms, it is quite probable that such a proposal is not unheard of, at least in policy circles. That said, the centralised civil service is here to stay, and we have to think about reforming it from within.

Everybody in the loop knows what ails the civil service: meagre salaries, skewed promotion policies, no security of tenure, political interference, and above all, compelling incentive for civil servants to be unscrupulous. Umpteen commissions have deliberated over these ailments and have recommended, among other changes, decent compensation packages, promotions based on performance rather than seniority, independence from political interference and a transparent accountability mechanism. Unsurprisingly, not a single recommendation has ever made it to the implementation stage.

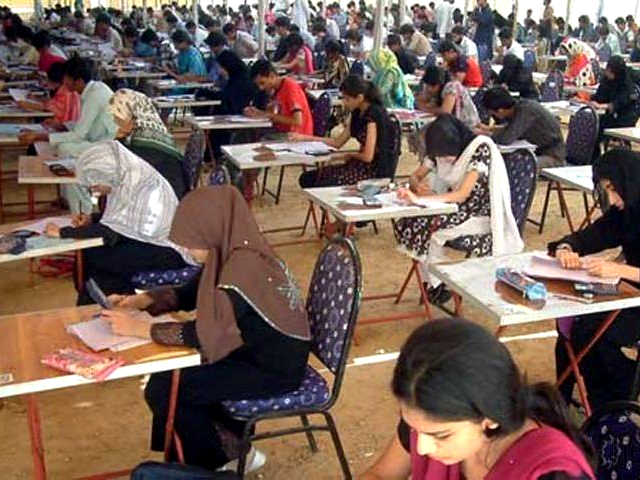

The entire civil service structure is so antiquated and out of sync with modern governance systems that it simply cannot deliver any meaningful service in its present form. Despite recommending changes in the selection process in its yearly reports, the Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC) finds itself administering the CSS examination according to the same old cumbersome process every year. The exam has lost its charm for the so-called ‘cream’ who once took pride in it.

Most of the candidates (including yours truly) who make it through the exam have in fact gamed the system – either through trial and error, which sounds reasonable, or through private coaching centres, which is unacceptable, or both. Despite valuing critical and analytical skills, the exam’s overemphasis on the English language as a measure of a candidate’s mental aptitude renders the playing field uneven. Nonetheless, the recent introduction of subjects such as gender studies is a step in the right direction, as it will greatly expand the mindset of candidates and also help the cause of gender sensitisation.

Every dispensation, civilian and military alike, has aspired to reform the civil service, and their efforts are always particularly spirited during their initial days, invariably leading to the establishment of a commission. Thus, our new prime minister is not really breaking new ground with the formation of the Task Force on Civil Service Reforms, headed by his Advisor for Institutional Reforms, Dr Ishrat Hussain. I cannot predict what reforms will be introduced in light of the aforementioned task force’s findings, but a year from now, we will at least have something to add to the pile of reports gathering dust in a damp corner of the Establishment Division.

However, if our premier seriously wants to reform the civil service, he ought to know that this effort will require iron political will and costly trade-offs. The reason why earlier endeavours could not bear fruit was not some deficiency in the proposed reforms; rather, it was the lack of political will on part of the government. Thus, whatever reforms the newly established task force proposes, be it the introduction of a National Executive Service that will essentially pave the way for lateral entry in the civil service, or the abolition of certain service groups, the prime minister will have to act decisively, without fear or favour.

The proximity of the beneficiaries of the current bureaucratic set-up (predominantly influential businessmen, the so-called electables, as well as a proportion of the bureaucrats themselves) to those in power and the rays of indispensability they emit soon leads to a change of heart, and the government loses all interest in the matter. The recent transfer of the district police officer (DPO) of Pakpattan under murky circumstances, as well as reports of some MNAs from the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) trying to influence postings and transfers of revenue officials, casts a dark shadow over Prime Minister Imran Khan’s resolve to bring about real change.

Nonetheless, one should remain hopeful that Imran, unlike his predecessors, will not forget the lesson that it is only the ordinary folk who are indispensable, as they are the ones who have brought him to power and only they can force him out.

For a citizen, civil service is the face of the state which they interact with on a daily basis. A revamped face will not just improve the quality of that interaction but will also restore the citizen’s faith in democracy, which is the surest way for Imran to remain in power while ensuring better functioning of the state as well.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ