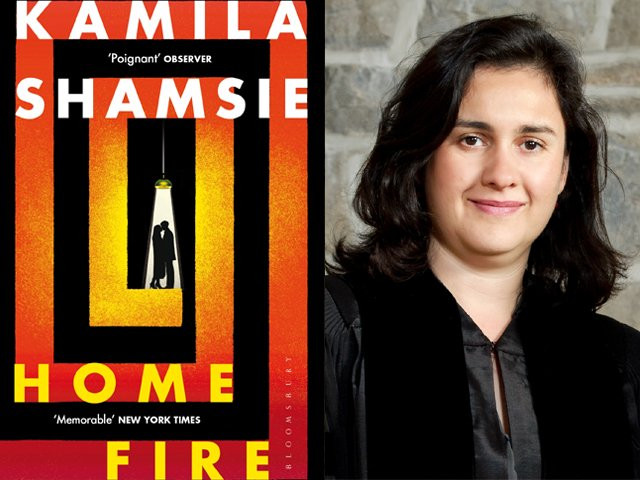

The cover of the book – one of the most profound covers out of the books in my possession – is a simple maze of red-orange fire with two lovers at its centre and a lamp over their heads. Like its cover, the book’s setting of the main characters at work in the plot is simple and profound. With the book divided into smaller parts for each character, we get to experience their stories from their perspective, as well as the tightly held tiny cosmos of wishes and old memories.

The story sets off with Isma, a British-Pakistani and the oldest of the three siblings, who is going to Amherst, Massachusetts for her PhD in sociology on a scholarship. She leaves behind her younger sister Aneeka, who is studying law at the London School of Economics on a scholarship. Aneeka’s twin brother Parvaiz has already left his sisters in order to avenge the death of their father Adil Pasha, who fought in Bosnia, Chechnya, and was then caught fighting with the Taliban in Afghanistan. After his capture, he was held at Bagram and died on his way to Guantanamo.

Being the eldest, Isma has fed the siblings since their mother died, when the twins were 12 and she was 21. Having just graduated from LSE herself when her mother passed away, she worked several jobs to provide for her siblings while their father was absent from their lives.

On the other hand, we see Karamat Lone, a British-Pakistani and the Home Secretary, who has become an atheist overtime yet continues to recite Ayatal Kursi in times of fear. Karamat also has a son Eamonn, whose name is thought to be Aimen, but he is given this Irish tag to prove Karamat’s loyalty to British values.

Home Fire is a story that encapsulates the fire that exists within a country, within one’s own self, and within the loyalties we place. The novel is a simple story of love blooming and trying to work through the harsh realities shrouding the characters. It’s a love affair between Eamonn and Aneeka, who wants to get her twin brother back to England with his help, but in doing so starts to fall for him. Eamonn has already met Isma in America, but falls for Aneeka. We get to see the story of their love, the choices the two make to provide what they can for the ones they love the most.

The last lines of the book are where Shamsie shows the reader the want of being there, of being wanted through and till the end, no matter what the end is, no matter what it might bring.

“For a moment, they are two lovers in a park, under an ancient tree, sun-dappled, beautiful and at peace.”

This line is what Home Fire is about. The shards one has to choose from what’s leftover.

Through this book, Shamsie delineates what it is to be a Muslim in a world fraught with nationalistic agendas, with ideas that are too large and too fragile to be discussed when it comes to love – for a sibling or for a lover. She shows what it is like is to be a Muslim, from covering one’s head to the frequent interrogation, suspicion, and constant worry to be careful no matter what you do; be it searching the internet, drinking, not drinking, believing, not believing, falling in love, or even going further.

In these times of nationalistic outpouring and extreme narratives, Shamsie shows how the world – be it England or Pakistan – takes away the right to make our own choices and has a stringent way of judgment.

It’s the small details in this simple story that make the reader engrossed in it. It’s in the way Shamsie describes bay takkallufi (uninhibited) in the following lines,

“I wouldn’t say intimacy. It’s about feeling comfortable with someone.”

It’s the social inequality with which Isma is judged at the airport, her belongings being inspected because she is a Muslim who covers her head, but also because of the quality of the material. It’s in the conclusion that makes the reader look forward to the story while knowing the tale is of two doomed lovers.

Home Fire is a story that builds slowly, taking the characters and the readers along on a journey. Yes, the story has a simple ground for some heavy political work, appearing a bit whitewashed, with westernisation infused within the dynamics of Pakistani pop songs when describing what it is like to be a Muslim, especially if one has a dual nationality. Nonetheless, it slowly builds on towards a story that asks simple and plain questions at hand, with characters tugged by difficult choices they have to make, no matter how controversial or painful, because ultimately they have to wade through the warring paths of emotions to fulfil the responsibility of love.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ