As part of my work, researching the academic standards of public schools in Lahore, I sometimes visit the Government Primary School in the Township area of Lahore.

Township is a working class neighbourhood - most of the people who live here work in factories in the Kot Lakhpat Industrial area. It’s relatively clean and less congested than other neighbourhoods.

The Government Primary School has an area of nearly 5,000 square yards - the covered area is less than 1,300 square yards. The rest of the area is occupied by thorny bushes and burning dumps of garbage, enclosed by a low-rising boundary wall.

Most of the school property is disputed - nearby residents claim it to be the place of a planned mosque, while the head teacher claims it to be part of the school.

The head teacher, Mr Qadri, is in his late 60s. He sports a long white beard, wears fake Ray Ban sunglasses and a loosely tied turban. He’s a wily character who is quick to thrash his students in the back of their heads at the slightest breach of ‘good conduct’. The oldest student in his class is 13-years-old.

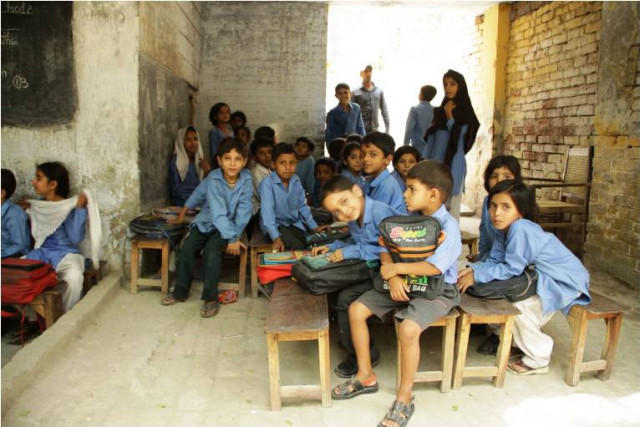

The classes are dimly lit, the windows are broken, the washrooms stink from a distance and electric wires hang loose from the ceiling. Mr Qadri has decided to use funds given to his school, for the next financial year, to buy staff furniture, which includes a plush pink sofa for the staff room.

Half the students of the entire school are crammed into one classroom, while the other half are divided into two classrooms a little further away. Divisions are not based on class-level, or even sections - children of all ages sit together.

When I arrive, the teachers are sitting in the shade of the veranda, sipping tea and smoking cigarettes. The students are in their classrooms, doing whatever pleases them.

Mr Qadri is proud to proclaim that he is also has djinns under his control, and he employs them to cure the sick. But that’s just his side business. His full time job entails a lot of hardship - chief among them is load shedding and the lack of resources to upgrade the school. The meagre funds he gets from the government can only be attained after paying a ‘fee’ to the local official from the education department.

At this point, I fold my notebook and head towards the education department.

The education department is located on Hall Road, after you’ve crossed through all the electronic stores. The department has two crumbling buildings separated by an unkempt garden. There are people, carrying loads of files, milling around the offices.

The largest office in the building belongs to the Executive District Officer; you have to have an appointment to meet him. In order to have an appointment, you have to have a reference. So I ask around for the officials who supervise primary-level schools.

It turns out that Mr Qadri is supervised by a long chain of bureaucrats: beginning with a Deputy District Officer and ending with the Executive District Officer. Each of these officials has at least three people working for him or her; one person to fetch tea, the second for looking up files, and the third to make calls from a telephone that’s sitting on their desks. Nearly all of them sit between metal file cabinets. And then there are files sitting on top of the file cabinets.

It’s impossible to have a conversation with any of them; they are constantly pushing files from one office to the other for no apparent reason. When they do find the time to turn to me, they have a long list of complaints to explain away the dismal state of public schools: mainly that they do not have the resources to meet the needs of their schools.

It appears, though, that even if they did have adequate resources, the government machinery itself would eat them all up.

If you took a black and white picture of the education department and the schools at work, you wouldn’t be able to distinguish them from a picture that was taken fifty years ago.

The djinns at Pakistan's public schools

One cannot distinguish a picture of the education department today and that which was fifty years ago.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ