Following the result of the Central Superior Services (CSS) exam every year, numerous analyses are raised, largely outsider points of view commenting on its so-called decline.

Such run-of-the-mill analyses blame the dismal state of education in Pakistan, the faulty examination system, the indifference of fresh graduates in regard to joining the civil services, the constantly deteriorating quality of candidates as compared to the bureaucrats from yesteryears, (including those who happen to pass the exam).

There is no denying the fact that the education system in Pakistan is constantly facing a downhill slump. Yet, this decline is often associated with insufficient spending on the sector, which to be honest, is misleading (the education budget is closing in on the official defence budget, at Rs790 billion and Rs860 billion respectively). Salaries of teachers have increased manifold since the 80s, yet the standard of education has been weakening since then.

The raise in salaries, still inadequate though, is not backed with enhancing the skill-set of the teachers or evolving the syllabi so that it may synchronise with the fast-changing needs of the society. There are self-motivated teachers, the lone-shepherds, and then there are those who are not, the vast majority.

Owing to systemic administrative and planning failures, the education system in Pakistan is producing homogeneous brain models in excess, who later find themselves incapacitated in a competitive environment. Resultantly, in a country producing thousands of graduates and hundreds of PhDs every year, only a few thousand appear and a couple of hundreds pass the CSS exam.

An analysis suggests that CSS is not looking for creative, perceptive and competent students. This could have been assumed only if the education system was producing creative and perceptive candidates who failed the CSS exam. The existing education system instead destroys the potential for authentic creativity and produces crammers –there are exceptions and it is probably these exceptions which are able to make it to the final list of selectees in CSS.

Since such an analysis builds on isolated/personal examples and is subsequently generalised, allow me the liberty to quote my personal experience of the CSS exam. I passed in my first attempt, despite working a full-time job and a personal indiscipline towards exams. I watched Million Dollar Baby (don’t try this at all) the night before my essay and comprehension exam – the Achilles heel for majority of the candidates – while my doctor friend crammed essays from some book for days on end.

I passed, he failed. But I probably passed due to my long cultivated habit of reading and writing beyond exams. During the Common Training Program (CTP), I met various colleagues who I believe will stand out amidst large crowds for their inspiring and creative sensibilities.

To say that the CSS selection test places more weight on ideological conformity and pliant behaviour is just another myth. To quote another personal example, there was a group of seven candidates including myself who were undertaking the psychological test and group discussion as part of the CSS selection process. The non-conformist of the group put forth a substantive argument stating that the separation of East Pakistan was a national blunder and Pakistan was still repeating the same mistake in Balochistan. Surprisingly, he received the highest marks and that too while the chairman of Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC) was a retired military general.

To say that the quality of the CSS aspirants, including those who happen to pass the exam, is constantly worsening as compared to the bureaucrats from the good old days, is yet another analysis conducted under the spell of romantic nostalgia.

There have, no doubt, been inspiring oldies, the salt of the earth, and the epitome of integrity, grace and resourcefulness for solving complex public problems. Mr Azam Mohammad Khan (retd), a seventh Commoner Commerce and Trade Group officer, with whom I served in his last year of service, was the perfect personification of all that we admire about the older generation. The man was an institution in himself, a professional giant, and there would be numerous individuals like him who are unfortunately forgotten in anonymity.

But, at the same time, there are equally a large number of officers in this generation who are able, upright, driven, and competitive. My first boss and mentor in the service after the completion of my CTP and Specialised Training Program (STP), Mr Khalid Hanif, an officer just three years senior to me, came from a similar humble background as that of the majority of the CSS officers.

He graduated from a government college. This same individual won an international scholarship to pursue an LLM in international trade law and then went on to work as a national consultant for a Geneva-based international trade organisation. Mr Hanif personifies many like him, who go unnoticed and are wasted by the system despite their huge personal potential.

What fails this new generation of Civil Services Pakistan officers is not where they come from and the quality of their talent, but what is made of them once they join service and how an opportunity to groom an officer with the right skills is wasted.

One must understand that holding ones ground against political pressures and maintaining integrity is not a cause, but an effect of an officer’s character sustained by his expertise in his work and job satisfaction. The civil servants of this generation, during their CTP, are trained into similar subjects (theoretical in nature) with focus on district management and revenue collection, as were the civil servants from the 50s and 60s, to the utter disregard of changing realities of population and public service requirements. Despite their personal spark and potential, they end up being generalists and that too, predominantly academic ones.

A Basic Pay Scale (BSP) 17/18 officer takes home Rs50,000 to 60,000, besides house rent allowance. Now if he were to be posted in Islamabad, he would not be able to rent a house within his budget, except for in the suburbs. Half of his salary is spent on transportation, and with the other meagre half, he resists or gives into political pressure and other temptations.

Income inequality within various service groups of civil service is so stark that “all animals are equal but some are more equal”. However, even those with an advantageous income – Police Service Pakistan (PSP), Pakistan Administrative Service (PAS), and Inland Revenue Service (IRS) – fall short of living a life of dignity once they have to afford two school going children.

The system is so warped that there is no room for grooming specialists – an imperative for meeting the changing needs of our society and economy. Officers trained for managing the districts are posted abroad to manage international trade; those trained for managing international trade are pushed to manage deputations in other organisations with relatively better remuneration.

The systemic degeneration and indifference has forced an inertia and meaninglessness upon the otherwise brilliant and full of potential new age bureaucrats. Their talent is not exploited but killed. Their remnants, lost in their own existence, can be found on Facebook and other social media platforms solving metaphysical riddles, mutually complimenting each other’s profile pictures in fulfilment of a delusional aggrandised self – a self they could become given the right skills and incentives leading to more engagement in public service.

The dreamers themselves have become, somehow a yonder dream.

The decline in Pakistan’s civil services is no longer a myth but a stark reality

Income inequality within many service groups of CSS is so stark that “all animals are equal but some are more equal”.

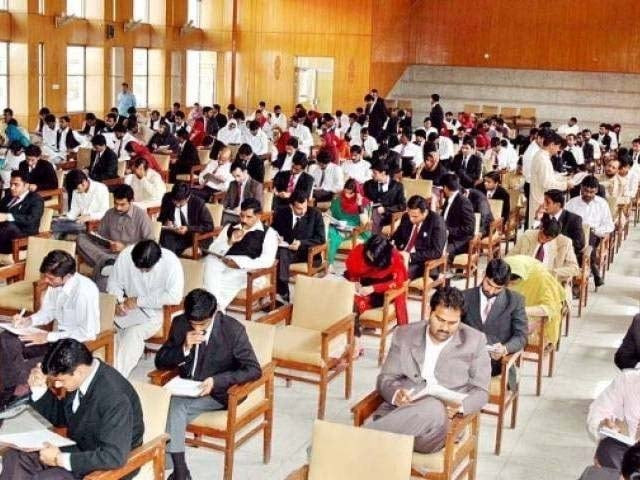

An analysis suggests that CSS is not looking for creative, perceptive and competent students. PHOTO: FILE

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ