We lived in Ruwais, a small town in the United Arab Emirates, where my father worked in an oil plant and my mother was a teacher. At school, I always stood out among the girls in my class—I was brash, clever, outspoken. I took pride in acing every test. When I brought home top marks, my father would celebrate by handing out sweets.

One day, when I was in Grade 10, I was in my bedroom doing math homework. My mother walked in. She told me I’d received a marriage proposal. I laughed.

“Mom, what are you talking about?” I asked.

She didn’t crack a smile, and I realised she was serious.

“I’m only 16,” I said. “I’m not ready for marriage.”

She told me that I was lucky. The offer came from a nice man who lived in Canada. He was 28-years-old and worked in Information Technology (IT). His sister was a friend of hers. The woman thought I’d make a perfect match for her brother—I was very tall, and he was six foot two.

“They’re going to look so great together in pictures,” she had said to my mother.

For weeks, I pleaded with my mom not to make me go through with it. I’d sit at the foot of her bed, begging. She would tell me it was for my own good, and that a future in Canada would give me opportunities I wouldn’t have here at home. She assured me that she’d spoken to his family about my desire to continue my education.

“You can go to school in Canada. And we don’t have to worry about you being alone,” she said.

The next thing I knew, his parents were measuring my wrist for wedding bangles. The date was set for five months later, in July 1999.

My friends would talk about their own dream weddings—the gowns they would wear, how they planned to be dutiful wives and homemakers. When I told them about my doubts, they thought I was crazy, that I was a fool, that Allah would punish me for being ungrateful. Marriage was their ultimate goal in life. But I didn’t want it. I just didn’t know how to get away.

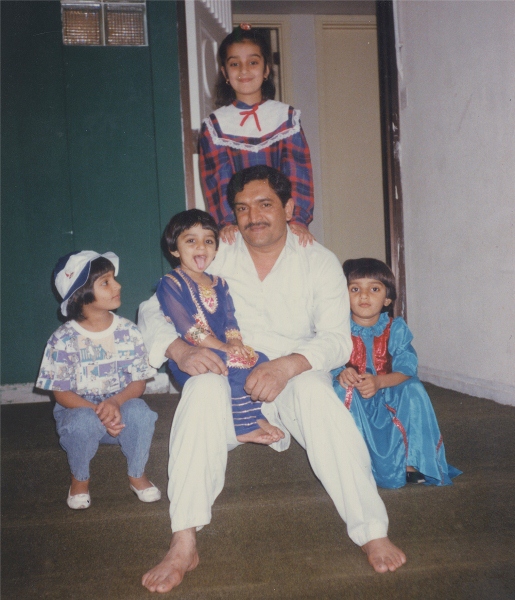

The author, top centre, at age seven, shown with her father and three younger sisters at their home in the United Arab Emirates.

The author, top centre, at age seven, shown with her father and three younger sisters at their home in the United Arab Emirates.For the next few months, I had recurring nightmares about my impending marriage. In my dreams, I was trapped inside a house, watching from the window as students made their way along the sidewalk to school. I’d wake up sweating and scared in the middle of the night. My mother would try to calm me down, telling me I was being hysterical.

One night, when I woke up screaming, she decided to do something about it. She phoned my future husband in Canada and allowed me to speak to him for the first time. All I knew about him were those few details my mom had shared with me the night he proposed. When I picked up the phone, I was meek. I only had one question:

“Will you let me go to school?”

He reassured me:

“Yeah, yeah, I’ll let you go to school. Don’t worry.”

The first time I saw him was on July 22, 1999, the day before the wedding, at his family’s home in Karachi. As we sat sipping tea, I snuck furtive glances at the man who was going to be my husband. I felt dwarfed by him.

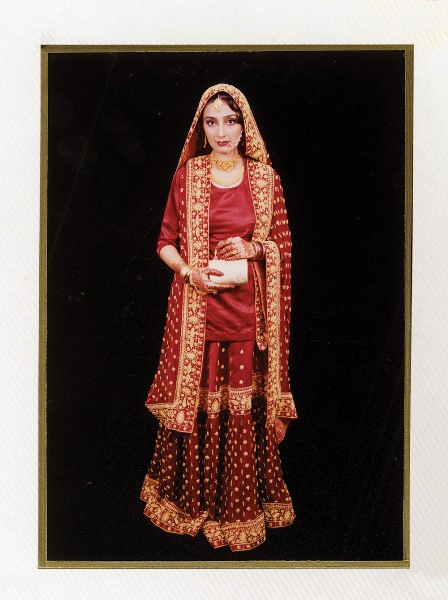

The author was just 16 when she learned she would be marrying a 28-year-old IT worker in Canada.

The author was just 16 when she learned she would be marrying a 28-year-old IT worker in Canada.The next day, we were at my grandfather’s house for the wedding. As my mother adjusted my gown, I pulled back. I told her I wanted to run away.

“Don’t be silly,” she said. “All the guests are here.”

Someone put the marriage licence in front of me, I was told to sign it, and I did. Later we held a celebration at a high-end restaurant in the city. Strings of lights and red ribbons decorated the room, and 200 of our parents’ friends came. There were piles of food, and everybody laughed and sang and danced long into the night. I wore a long red lehenga sari. I was told to sit there quietly and look down at my hands, playing the demure bride.

The author on her wedding day at age 17.

The author on her wedding day at age 17.This was the first of two ceremonies—we had to make it official so that my husband could apply for my sponsorship in Canada. The second ceremony was still months away, as was my wedding night. In the meantime, I continued to live with my parents and attend school. My new husband stayed in Pakistan for a month. We saw each other a few times, but never for long and usually with others around.

One evening, we went to Pizza Hut with his older brother and his brother’s wife. It was my first date, and I was so shy I barely spoke. We talked regularly online, over MSN Messenger, and occasionally on the phone. Slowly, I grew more comfortable with the marriage. Nothing about him struck me as special. He wasn’t smart or funny or warm, but he was a normal enough guy. He told me how pleased he was that his wife was so smart. He suggested university programs I should consider in Canada. He agreed to wait to have kids until I finished school. He said all the right things.

When my immigration papers came through in August 2000, we both flew to Abu Dhabi for our second, smaller celebration. After it was over, we slept together for the first time. I was petrified. I knew nothing about sex or birth control, and neither did he. My aunt had told me about ovulation, explaining that I couldn’t get pregnant if I had sex on certain days of the month. I thought our wedding night was one of those days. I’d never even seen a condom before.

Later that week, we flew to Canada and I moved into his two-bedroom condo in Mississauga. I missed my parents, my friends, and my school. I was so unhappy that I stopped eating, and I spent most of my days watching TV while my husband was at work. I stopped getting my period right away. At first, I thought it was because of the move, the abrupt change in environment. But a month passed, then another. I was getting sick every morning. My nausea was so severe that I was afraid to go outside in case I fainted.

Finally I told my husband that I needed to see a doctor. I sat in the doctor’s office, listening to him ask me if I understood what being pregnant meant. All I knew was that it meant I couldn’t go to school. This can’t be happening, I thought. This isn’t happening. I was only 17.

During the first few months of my pregnancy, my husband was kind and thoughtful. He took late night trips to the grocery store to satisfy my cravings. He’d call a couple of times a day from work to ask how I was feeling, and every night we cooked dinner together. I discovered an adult learning centre near our condo and enrolled in an English as a second language (ESL) course. I thought our marriage was going well.

Then, two months before our daughter was born, he told me his parents would be moving to Canada and staying with us. He had planned for them to live with us all along, but this was the first I’d heard of it. We moved out of the master bedroom into the smaller one so his parents would be more comfortable.

Everything changed when they arrived. My husband and I stopped spending time alone together. His mother got upset when he paid attention to me, so he didn’t show me any affection. When I would ask if I could call my parents in Ruwais, he or his mother would tell me we couldn’t afford international calls.

In May 2001, I gave birth to our daughter. When we returned from the hospital, my husband slept on the couch while I stayed with the baby in the second bedroom. I’d never felt so alone. I fantasised about stealing money from my husband’s wallet and taking a cab to the airport, calling my parents and asking them to buy me a plane ticket home. But I didn’t want to leave my daughter behind.

When she was a few months old, we bought a four-bedroom house in Streetsville with his parents. I was rarely allowed to leave. I never had a penny to my name. My mother-in-law gave me her cast-off clothing to wear. I didn’t have a cell phone. I wasn’t allowed to go to the grocery store on my own. If I didn’t iron my husband’s shirts or make his lunch or finish my chores, he and my in-laws told me that I was a bad wife who couldn’t keep my family happy. I walked on eggshells all the time. If I asked my husband something, he would reply,

“B****, get out of here.”

Two years in, the abuse got physical. He would grab my wrist and shove me around. I’d be sitting on the couch and he’d slap me upside the head, or grab me so hard on my upper arms that my skin would bruise. Once he tossed a glass of water in my face; I slipped on the floor and threw out my back. Another time he punched a hole in the wall next to my head and told me,

“Next time, it’s going to be you.”

On several occasions, he picked up a knife and said he was going to kill me and then himself.

I was having suicidal thoughts all the time. I was convinced my life was over. One time, I took a razor blade into the shower and thought about cutting myself, stopping only when I heard my baby cry. I believed my unhappiness was my fault—that the secret to perfect wifehood was eluding me. If I’d just done the dishes better, been quieter, anticipated that he wanted a cup of coffee or a glass of water, then none of this would have happened.

When my daughter turned three, I learned about a parent drop-in centre called Ontario Early Years, funded by the Ministry of Education. Located in a Streetsville strip mall, the space was bright and cheerful. My daughter would make crafts or play with play-doh, and the parents would gather in a song circle with their children and recite nursery rhymes. My husband took my daughter and me there a couple of times. Eventually, he let me walk over on my own. I looked forward to those two afternoons a week, when I’d be allowed to step outside by myself without fear, when I’d feel fresh air on my face.

The woman who ran the centre was Pakistani, and she recognised some of the signs of abuse even before I knew what to call it. She saw how jittery I would get if the sessions were running long, or how I’d have to ask permission from my husband if there were any changes to the schedule. She let me use the phone to call my parents. I tearfully told my father what was happening, that I felt imprisoned and helpless. He was horrified, but advised me to wait until I got my Canadian citizenship.

“That way you won’t risk losing your daughter,” he said.

And so I waited another year. Throughout this period, I resumed my education, taking high school courses by correspondence. I applied to university several times. I was always accepted, but my husband would never pay the tuition.

In 2005, I told my husband that I wanted to go home to visit my family for four months. It had been five years since I’d last seen them. When he told me he didn’t have the money, my father sent plane tickets for me and my daughter, who was four by then. On my way to the airport, I asked my husband for $10 to buy myself a coffee and my daughter a snack.

“B****, go ask your father for that too,” he told me, as he dropped me off at Pearson.

When my parents picked me up at the airport, they almost didn’t recognise me. I’d lost so much weight I looked skeletal.

My family were shocked. The bright, confident girl they knew had been replaced with a skittish, scared young woman. It took a couple of months for me to realise I could go to the mall on my own, or to the grocery store. These were small triumphs, but they helped build up my confidence. By the end of my visit, I was resolved not to go back to Canada. As soon as I delivered the news to my husband over the phone, he unleashed a flood of apologies. He told me he’d never hurt me again. He promised we’d move out of the house, that we’d live alone together like we used to.

He wore me down. In August 2005, I returned to Canada. We moved into a new apartment, and my husband was paying both his parents’ mortgage and our rent, leaving little money for anything else. At first, he was kind again. But within a few months, I got pregnant with our second daughter, and the abuse resumed. I needed an escape plan, so I began tutoring and babysitting children in our apartment building, slowly saving money for five months until I had enough for my daughter and me to fly to Karachi, where my sister was getting married. This time I wasn’t coming back.

My father had been diagnosed with kidney failure before I’d arrived in December, and over the next few months I watched helplessly as his condition deteriorated. One day, I sat with him in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

“Papa, if something happens to you, what am I going to do?” I asked him.

“Realise the strength you have inside of you,” he told me. “Go back to Canada and find a way to get out of your marriage.”

He died two days later. My husband arrived in Karachi that week for the funeral. Sex was the first thing he wanted. It wasn’t until he’d finished that he asked me how I was feeling. I said I was fine, got up and walked to the bathroom. I turned on the shower so he wouldn’t hear me cry.

When I asked my mother what to do, she told me I should go back with him. After all, she had two more daughters to marry off, she said, and she didn’t have the money to support me. I couldn’t work. I had no education or experience. And I was pregnant. Resigned and defeated, I went back with him. While I’d been away, he’d moved back into his parents’ house. This time I got a small room in the basement, with bare walls and a little window in the corner. My daughter slept in her crib in the room next door. In June 2006, I gave birth to my second daughter. I was miserable.

And yet my father’s words had ignited something in me. I knew I was smart, and I knew the only way out was through school. I studied in my room every night, finishing the last course I needed for my General Education Development (GED), a Grade 13 economics credit. A few months after my younger daughter was born, I earned my diploma, and decided to apply to university again.

I knew my husband would never let me leave the house to earn money for tuition, so I resurrected my babysitting service, telling him I was earning money for the family. I co-opted my mother-in-law with the promise that she’d earn easy money taking care of kids, and my husband even let me buy a van to drive my charges around. I was making between $2,000 and $3,000 every month, and though I had to turn over my earnings to my husband, I managed to sock away a few hundred dollars here and there. It took me two years to save enough for one year of school.

In 2008, I applied to University of Toronto’s (UoT) economics program. I was accepted. Nothing was going to stop me from going.

“Who’s going to pay for your tuition?” my husband asked.

“I am,” I responded.

My in-laws were so angry about my decision that no one in the house spoke to me for six months. I didn’t care. This was my chance to get out. It had taken me nearly 10 years, but I’d gone from victim to survivor.

My first day of school in September 2008 was one of the best days of my life. I got to school 15 minutes before my class started and walked through the Kaneff Centre at UoT Mississauga. After everything I’d been through, I’d finally achieved my dream. I sat in the hall, tears running down my cheeks. If only my father could have seen this, I thought to myself.

I thrived in my new environment. I aced every class, and other students gravitated toward me, asking to study or socialise. My success changed my thinking. If I was the scum on the bottom of my husband’s shoe, like I’d been told all these years, why were my marks so high? Why did classmates want to be my friend? I could feel vestiges of confidence I hadn’t had in years.

One day in October I was walking to the campus bookstore to buy textbooks. Just around the corner, outside the health and counselling centre, a flyer on a bulletin board caught my eye. On it was a list of questions.

“Do you feel intimidated? Do you feel like you don’t have a voice? Do you feel like you’ve lost your identity?”

As my eyes ran quickly down the list, my brain screamed over and over again: yes, yes, yes.

“Come in and make an appointment,” the poster read.

I opened the door and walked inside.

A few days later, I sat across from a counsellor, describing what was going on at home.

“I don’t know what to do,” I told her. “I’m trying to keep my husband happy and I’m still not good enough. He keeps telling me I’m worthless. All I want to do is fix it.”

She grabbed my hand.

“It’s not your fault,” she said.

It was the first time anyone had said that to me. As I continued my counselling, I realised that what had happened to me was wrong. My agency had been stripped away. I learned about the cycle of abuse that characterises so many unhealthy relationships.

Our marriage was becoming more toxic every day. He once bought me a cell-phone as a present, but installed spyware on it so he could monitor my calls. He kicked me in the stomach. He kept threatening to kill me. A year after I started counselling, I told him I wanted a divorce.

“What are you talking about?” he asked me. “I love you. I can’t live without you.”

One January night in 2011, he picked a fight. I wasn’t doing enough housework, he said. As he loomed over me, tightening his fist, I picked up my phone.

“If you touch me, I’m going to call 911,” I shouted.

And then he spat out the word divorce, in Urdu, three times: talaq, talaq, talaq. According to some Islamic scholars, uttering those words means the marriage is over.

I thought I’d be thrilled when he left, but I was terrified. I’d never lived on my own, and I was bracing myself for the shame I believed I would bring to my family. He sold our house out from under me, leaving me and the kids with three weeks to pack up. We had nowhere to go. I even registered at a couple of shelters, expecting to be homeless.

One day, I was at the UoT tuition office, and a woman overheard me lamenting my situation. She suggested I look into campus housing; luckily, the university had one family unit left. Two days later, I had the keys to my very own shabby three-bedroom townhouse.

I couldn’t afford movers. I packed all my belongings into garbage bags and made 10 trips back and forth every day for five days, in the van I used to drive the kids who attended my home day care. I used my last $100 to pay a couple of students to help me move my furniture. I was relieved not to be out on the streets. I slept in one room with my youngest daughter. My eldest had the second bedroom, with enough space just for a single bed.

I rented out the third room to a Pakistani student who watched my girls while I worked in the evenings. It was tiny, but it was ours. That year, I juggled five jobs to stay afloat. I worked as a teaching assistant (TA), a researcher with the City of Mississauga and a student mentor. I did night shifts at the student information centre on campus. I even ran a small catering business out of my apartment.

One day it dawned on me that my husband was a man willing to put his own kids out on the street to teach me a lesson. I drove to the police station and reported everything. I gave a three hour long videotaped statement, offering as much detail as I could about the decade of abuse I’d endured. The officer said he likely wouldn’t be able to lay charges because there weren’t any bruises on my body. But it didn’t matter. Just telling the authorities was a huge relief. It was my way of acknowledging everything to myself, of finally saying, it wasn’t my fault—none of it was my fault.

The officers interviewed my doctor and counsellors, and two days later they arrested my husband for assault. He pleaded guilty. We finalised our divorce, and he got joint custody. My older daughter refused to see him, but my younger daughter visited him every other week.

There were many times over the next year that I thought I’d made a mistake, that I couldn’t do it on my own. I thought the shame would never go away. After my marriage ended, none of my old friends would speak to me. My mother refused to tell people back home. I had no family in Canada, no friends at school who knew what was going on. I was completely isolated.

I’d always been told that women are responsible for upholding the family’s honour. A woman living alone is a sin. A woman travelling alone is a sin. When everybody around you says you’re in the wrong, that your dreams aren’t valid, you start to believe that. And there were many times that I’d fall into those sinkholes.

Zafar graduated from the University of Toronto at the top of her class.

Zafar graduated from the University of Toronto at the top of her class.Education was my only refuge from my dark thoughts. I focused all my energy on school. In my fourth year, I was promoted to head TA. I worked as a senior mentor for the school’s first-year transition program. I carried an eight-course load and earned a 3.99 Grade Point Average (GPA).

One day, I got an email from my department advisor. In it was a description of the university’s highest honour, the John H Moss Scholarship, a $16,000 award that’s given to an outstanding student who intends to pursue graduate work—the Rhodes scholarship of UoT. My advisor encouraged me to apply. No one from UoT Mississauga campus had ever won it, she said. The deadline was only a few days away, but she convinced me to hustle up the paperwork.

A few weeks later, I got an email saying that I was one of five finalists. I arrived for my interview on February 6, 2013. The committee ran through questions about my academic record and leadership experience. I’d written about my abusive marriage in my application, too, and at the end of the interview, the panel asked me how I go on after everything I’ve been through. My polish wore off in that moment.

“Every day I feel like giving up,” I told them.“But I don’t want my daughters to grow up thinking that being abused is normal.”

Forty-five minutes after my interview concluded, I got a phone call. John Rothschild, chair of the selection committee and the CEO of Prime Restaurants, was on the other end of the line with a few other panellists.

“Congratulations,” they said. “You’re our winner this year.”

I couldn’t believe it. I grabbed my daughters’ hands and danced wildly around the house with them. I wanted to tell the whole world. Since then, John has become a friend, a mentor, and the closest thing I have to a father figure. He taught me how to believe in myself again. He says if I ever get married again, he wants to walk me down the aisle.

Businessman John Rothschild funded her non-profit organisation for abused women.

Businessman John Rothschild funded her non-profit organisation for abused women.In September of that year, I started my master’s in economics. By the time I graduated, I was surviving off the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP), and my debt load was piling up. I wanted to stop borrowing money as soon as possible, so I decided not to pursue a PhD. Instead, I accepted a job at the Royal Bank of Canada, where I work today as a commercial account manager.

Around the time of my graduation, I was named the top economics student at UoT. At the award ceremony, a journalist introduced herself to me (her daughter was in my class). I told her my story, and she published an article about it in a Pakistan newspaper.

As my story circulated through the community, I received hundreds of messages from women all over the world trapped in forced marriages and looking for help. So many of them sounded like me five years earlier, isolated and helpless. Women who show up at shelters or call assault hotlines or leave their homes find themselves completely alone. Without any help, they return to their abusers or fall into new relationships that are just as bad. Once, while I was TAing at UoT, a father barged into my office yelling.

“You’re pushing my daughter to get her master’s degree!”

I couldn’t believe it. To me, it was natural to offer encouragement—his daughter was the top student in my class.

“She’s supposed to marry a boy in Egypt. Stop poisoning her with your Canadian bullshit,” he barked.

Years ago, a woman wrote to me asking if we could talk on Skype. She was a Canadian university graduate whose parents forced her into a marriage in Pakistan after she finished school. Brutally abused for three years, she returned to Canada to have her baby. She wanted to leave her marriage. After we finished talking, I drove to her house and encouraged her to do it.

“No one will ever love me again,” she said.

Three years later, she graduated from a master’s program and got a job working full-time in Toronto. I realised I couldn’t stop abuse from happening. But I could offer friendship to women in similar positions to my own. I started a non-profit called Brave Beginnings that will help women rebuild their lives after escaping abusive relationships. John Rothschild, my mentor, provided our start-up funding, and we’re piloting the project this year.

Zafar lives with her two daughters, age 15 and 10, in a condo in Mississauga.

Zafar lives with her two daughters, age 15 and 10, in a condo in Mississauga.For the past three years, I’ve lived in a three-bedroom condo in Mississauga with my daughters, who are now 15 and 10. I serve as an alumni governor at the University of Toronto, and I speak about my experience for organisations like Amnesty International. I’m happier than I ever imagined I could be. I want women to know that they deserve a life of respect, dignity and freedom—that it’s never too late to speak up. It infuriates me that many women are expected to uphold their family’s honour, yet they don’t have any themselves.

Last April, I called my ex. I wanted to help him repair his relationship with our older daughter. It had been four years since we had spoken in person. I decided to meet with him. Despite everything, I believed that my girls deserved to have their father in their lives. I sat in a coffee shop at Eglinton and Creditview Road, desperately hoping that I was no longer scared of him.

I saw him walking across the parking lot, and waited for an avalanche of fear to hit me. It never came. Sitting across from me, he was just another person. To my surprise, he apologised.

“I cannot believe after everything that you’re still willing to help me repair my relationship with our kids,” he said.

That day in the coffee shop, I finally felt free.

A few weeks ago, I lay in bed cuddling with my youngest daughter. Every night, we snuggle for 10 minutes before she goes to bed, just the two of us, unpacking the day. Out of the blue, she said,

“Mom, I think Daddy’s family picked you because you were only 16. They thought you were just going to do whatever they told you to do and they’d be able to make you into whoever they wanted you to be.”

And then she paused,

“Man,” she said.“They picked the wrong girl.”

All photos: Luis Mora

This post originally appeared on Toronto Life here.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ