“We can connect to any part of the world with one click. We can access any information in the spur of a moment. What else is connectivity?”

I partially agreed with what my friend had to say but I still wondered if we really are living in a connected world.

We live in a world where we are limited within our own small worlds, which are usually only as big as our mind-sets. And the territorial limits of our mind-sets are set up by the societies we live and grow up in. We develop perceptions, good or bad, over time. We cultivate perceptions about people, places, things, cultures, and religions we have never known, solely on the basis of hearsay.

I once read that if you want a lie to become a truth, you just repeat the lie several times until people start believing it unless they’ve experienced otherwise.

The sad part is that we are never bothered by our ignorance and more often than not, we make assumptions about people without any evidence at all. We aren’t ready to break out of our bubble – I’ve noticed how sometimes these notions become too hard to crack and lead to a certain hatred and disgust for others, so much so that if we even try to engage in a dialogue to render their perceptions, they get offended.

Let’s take a look at the bigger picture – despite all this apparent connectivity, non-Muslims still have the perception that Muslims are fanatics and terrorists, and unless they have a first-hand experience with a Muslim, that perception does not change.

Recently, I met a lot of people from different religions, faiths, races, and backgrounds in the United States, and their views about Muslims were no different. When I told them that I am also a Muslim, they didn’t even believe me. That is how far circumstantial assumptions can go. I overheard someone saying that if they hadn’t met me, they would still believe that Muslims were fanatics who kill others over difference of mind-sets.

It’s a universal problem that doesn’t solely exist in the West. In Pakistan, this problem isn’t any less intense. We are quick to assume and judge what we do not understand. For instance, when I visit other cities in Pakistan, people never believe that I’m from Peshawar simply because they assume that the city only has burqa-clad women that are not even given the right to basic education. If such vacuums can exist in our country, how can we claim to be so connected?

Recently, I had the privilege of meeting a Jewish family in the United States and honestly, it was no less than a treat. During the first week of my interaction with my facilitator, Eileen, I did not know that she was a Jew. We would speak about Pakistan and the United States, about culture, tradition, food, music, and the weather during our car rides. I remember the day when Eileen mentioned in passing that she was a Jew. I was delighted to hear that because I had never met a Jew before, and I couldn’t help but smile at the irony of the situation – here I was, in a different country, befriending someone of a faith people had told me negative things about all my life.

Ideas such as the Jewish lobby working against Muslims, that Jews always conspire against Pakistan, Israel does not like Pakistan, and the Israel-Palestine issue flashed through my mind. And then I remembered my green passport which states that it is valid for all countries of the world except Israel.

From that day onwards, Eileen and I would have discussions about religion and she would tell me about Judaism. The more she told me about it, the more I realised how similar our religions were. One day, while at a restaurant for lunch, I told her how I only preferred Halal food, and she told me how Kosher and Halal were one in the same. For someone who didn’t know, I was amazed to hear that. She also told me that in some orthodox Jewish communities, women and men don’t intermingle, the women cover their heads, and some don’t let their kids go to schools. I was fascinated to learn how connected we were, and how no one ever speaks about our similarities because we are too busy nit-picking at our differences.

I went to see their temple, saw them performing their religious rituals, and heard them reading from the Torah. I met the Rabbis and other Jews, and was overwhelmed by their warmth. I never felt that they hated me for being a Pakistani or a Muslim, even for a moment. They welcomed me into their community, and were curious to know more about me and my country as I was about them.

Eileen made me meet her entire family – her mother, a graceful lady who lives independently and is a librarian, her elder sister, brother-in-law, two little nieces, her husband, and even a family friend who is an Israeli and worked as a professor at a local university.

Since Eileen knew that I only ate Halal food, every time they invited me over for dinner, they took the liberty to prepare a Halal meal especially for me.

I remember how her mother never allowed me to take any form of public transport while I was there and insisted on dropping me all the way to my door every time.

“Just like I don’t like my daughter taking public transport at night, I don’t like you taking it either,” she would say.

One day, while crossing a temple, she pointed towards it and told me that this is where she got married. She went on to ask me about the weddings in Pakistan and I briefed her about the average four or five-day wedding functions, the average cost we bear for a wedding and the number of guests we invite. She was shocked. I also told her about certain traditions in rural areas where the whole village is usually invited to attend the wedding.

In response, she told me,

“My friend once went to Afghanistan and came across a wedding ceremony. They invited him in, and he felt extremely privileged to have garnered an invitation. When he arrived, he noted that there were hundreds of people there. So he asked someone why, and the man replied telling him that there, everyone is invited to every wedding.”

She spoke to me about her husband and her step-daughter quite often. I never heard her say a single negative thing about her step-daughter, and that made me so happy, since in our society, people are usually so spiteful towards step-relations.

I saw her crying the day Donald Trump won because she was really worried – worried about her people, about the immigrants, the African-Americans, the Muslims, and other minorities living in the US.

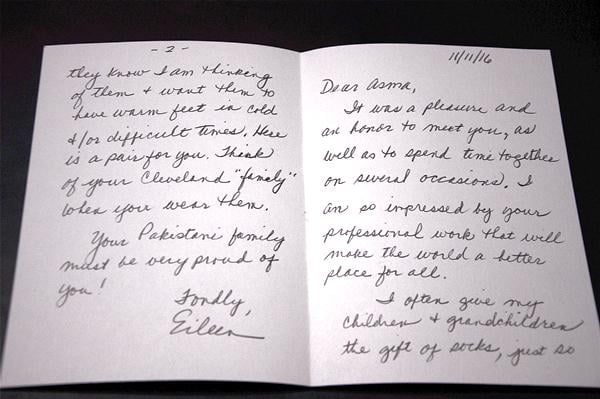

Before I was leaving the US, Eileen had given me a pair of socks and a note with it. At the time I didn’t quite understand the purpose of the socks, but once I read the note, I realised what a kind-hearted person she is, and how it’s so naïve to assume things about people on the basis of their faith or locality.

After meeting and spending time with Eileen, I realised that the only way to eradicate our misconceptions and break out of our little bubbles is to meet people, to come forth and try to understand other religions, cultures, and values with an open mind. We must always remember that there are two sides to every story and every person and it’s unfair to label others based on certain stereotypes.

Thus, connectivity isn’t just about technological advancement; it’s about cross-cultural interactions and the development of new relationships. Because technology can never replace personal contact, even though today, it seems like it can. We have to realise that in order to grow, we have to expand our bubble, and the only way to do so is through interactions.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ