My Egypt moment wasn’t when the protests started or when they ended. It wasn’t during CNN’s live coverage, and it wasn’t in the 100 or so ‘Can this happen in Pakistan?’ discussions. It was when someone casually yelled out in the school corridor, “Hey Meiryum! Your hometown’s burning!”

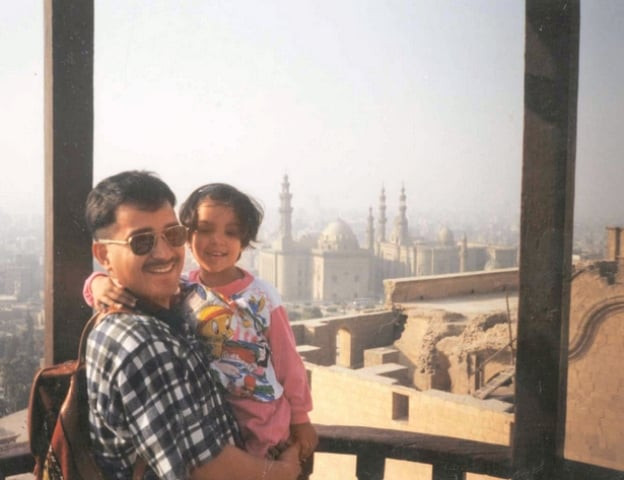

Cairo was my hometown. Tahrir Square was a 45-minute drive from my apartment. I lived in Cairo from the age of four till eight years - four years of my life. I was old enough to remember and store away memories and young enough to still understand nothing.

My first day at the ‘big’ school (ie not a Montessori) was in Cairo. My first real friends, the ones you could call over to your house without asking mummy, trace back to Cairo too.

Cairo was my home. Karachi was Mummy and Baba’s home. Pakistan was an event you attended each 14 August at the Ambassador’s residence, with some kid called to sing ‘Lab pey aati hai dua’ while you picked threads off your itchy shalwar kameez. But I was the kid who learnt ‘Wahid, itnain, talata’ before I did ‘Eik, do, teen’. Being called a ‘Bakistani’ wasn’t an insult, but it sure was confusing.

So when Cairo exploded on BBC and CNN, I sat up. I was fascinated. I texted my bemused friends. But I wasn’t interested in what the protesters were saying, though I pretended to be. I was interested in the background buildings, the different accents and the Arabic pop music playing. I was interested in a country I hadn’t seen in eight years.

Yet, the more I watched it, the more I realised that I didn’t seem to know Cairo at all, even when I was living there.

Everything I did, and saw, was from the eyes of a foreigner, more specifically, a foreigner’s little daughter. Tahrir Square was a stop on the Metro for me, enroute to ‘Baba’s office’. When I Google-map Tahrir, the only landmark near it that I can recognise is the World Trade Centre, which I remember because the lobby contained a life-size Minnie Mouse.

I can count on one hand the Egyptians in my class at the international school I attended: two! There were almost 10 times more desi (Pakistani and Indian) kids.

In fact, which Egyptians did I know? The ones behind the counters in the shops and restaurants I visited, the cleaning lady, the driver. I lived in Maadi, a locality where all foreigners lived in leafy, clean streets. This was in direct contrast to the polluted, congested foothills of Muqattam.

What was the biggest complaint I could think of when I visited Saddar, on holiday in Karachi? ‘Mama I don’t like. It’s too much like Muqattam.’ I would come to adore Saddar, but not then, not when I was six years old and too used to Maadi. I watch a CNN foreign correspondent on TV and all I’m thinking is, ‘I know you. Your son was in my class.’ The point being, of course, if I really knew Cairo, then I wouldn’t recognise him at all.

But this is the Cairo I know, and I can’t change that. I can’t help that my memories are a mixed bag of ice-cream parlours and pyramids, that every Egyptian I ever met was smiling and seemed happy to see me. If I was supposed to analyse Cairo and its citizens and their problems, well, that wasn’t my job. Cairo for me was an idyllic childhood: hot summers, cold winters, curly haired people.

And among other firsts, Cairo was where I witnessed my first protest. I don’t remember how old I was, but I was standing on top of my Powerpuff Girls table to get a better view through the window: the road right opposite my apartment was shut down. Protestors were marching shoulder to shoulder, blocking traffic. The whole thing was eerie. There were no cars, none, and the protestors were all in neat, orderly lines.

“What are they marching for?” I asked the cleaning lady, who was silently watching the scene along with me. She spoke hardly any English, and I don't know Arabic, but I caught the word Israel in her speech. “They like Israel?” I asked.

“La!” she cried, shaking her head emphatically. I thought a bit.

“They like Palestine?” (How do children connect the dots? Because there was a Palestinian boy in my class, who I remember for always writing the digit 7 upside down).

“La,” she said again.

“But then, why are they marching?” I asked, amused.

I never knew what happened to that march, never knew if it was covered on the evening news, and never knew if the police broke it up. That afternoon it was as if the cleaning lady and I were the only bystanders to a mysterious event. And because she never mentioned it again, I thought maybe it never happened, that I had made it all up.

But I hadn’t. These last two weeks I wasn’t the only observer to a series of protests, and now I know the reason for the marching. And for a little while, this 16-year-old Bakistani girl feels like she’s found the missing piece of a familiar city, that’s she home again in Cairo.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ