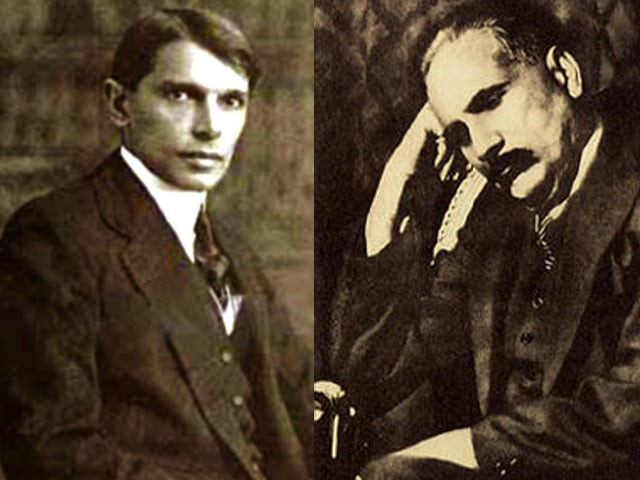

Iqbal was, at various times, a Muslim modernist (he endorsed the founding of secular Turkish republic as a seminal event in Islamic history), a Muslim reformer (his lectures compiled as the Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam show the breadth of his reformist vision) and an uncompromising Islamist believing in theological unity and purity of the Muslim community (his views towards the Ahmadis towards the end of his life are an indication of this).

The undercurrent of Islamic identity was always evident in Iqbal’s poetic endeavours. It is important to place him, for after all a person is a product of his social and material conditions. Mirza Ghalib was the poet of Muslim political decline and embodied the despondence of the Delhi’s Ashrafia at the loss of political power. Iqbal was the poet of Muslim resurgence and revival embodying the growing aspirations of a nascent Muslim middle class. His poetic classics Shikwa, the lament, and Jawab-e-Shikwa, the response to the lament, encapsulate his thinking from very early on.

The idea of the loss of Muslim political power had been the preoccupation of many modernists amongst Muslims, most notably Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. A recurring theme in this line of thinking was the idea of ‘theft’ - worldly progress and glory was the inheritance of the Muslims stolen from them by the West. In the lament and its response, Iqbal strongly emphasises this theme. His solution was a subtle departure from Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Whereas Sir Syed Ahmad Khan only exhorted the Muslims to edify themselves with western education, Iqbal pointedly refers to the failure of Muslims to live by Quran, which he argues the West has already done. He also denounces mindless aping of the west by pointing out that Muslims dress and act like the Christians and Jews, while Christians and Jews have internalised the lessons of the Quran. This idea took a life of its own.

Iqbal’s earlier outlook on Muslim identity was decidedly inclusive rather than exclusive. This explains his close ties to the Ahmadi community and his effusive praise for Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of that sect (such was his closeness that there is speculation that Iqbal had converted to Ahmadi beliefs at one point in his life).

By the 1930s, however, Iqbal’s views seem to have undergone a sea change. Iqbal argued for a separate status for Ahmadis as a religious community. In his essay, Islam and Ahmadism, a rejoinder to Nehru’s articles on the subject, Iqbal exposes his basic anxiety; solidarity of Islam and the danger impacting it by the ideas propounded by Ahmadism. Arguing that the founder of Ahmadism, who he had praised earlier, may have heard a voice, he puts it down to spiritual impoverishment of the Muslim people. He proceeds to vilify Ahmadis as pre-Islamic Magianism which takes on – or steals – the important externals of Islam.

The idea of theft comes into play. Iqbal argues that the finality of prophethood is the key to establishing Muslim solidarity and that Ahmadis, by denying this tenet, would cause the pre-Islamic Magian condition where societies would be broken down and recast in a new light. As a corollary of this argument Allama Iqbal goes on to argue against religious tolerance or the state’s indifference towards being “harmful” to religious communities. In other words, Iqbal was opposed to absolute religious freedom.

Therefore modern historians of thought in Pakistan must grapple with the fundamental discord between Iqbal’s ideas and Jinnah’s vision both of Muslim solidarity and religious freedom. Jinnah as the leader of the All India Muslim League repeatedly ruled out the idea that Ahmadis could not join it. Contrary to Iqbal’s view of Muslim solidarity emanating out of theological consensus, Jinnah’s test was simple: if a person professed to be a Muslim, he was welcome in the Muslim League.

This became a major point of contention in Punjab, where elements in the Punjab Muslim League wanted to exclude Ahmadis from the Muslim League on the ground that Ahmadis were non-Muslims. Simultaneously Jinnah was attacked by pro-Congress Islamic parties like Majlis-e-Ahrar and Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind for his tolerance of Ahmadis in the Muslim League. However Jinnah did not budge from his principled position on the issue, going so far as to call such theological and sectarian issues as a danger to Muslim unity.

Similarly, Jinnah was a lifelong advocate of the state’s neutrality in matters of religion – an idea which Iqbal considered as problematic. Throughout the Pakistan movement Jinnah promised freedom of religion as a cornerstone of the future state of Pakistan and on August 11, 1947, as the founder of the country, he made his policy plain once again in that memorable address. Jinnah was also wary of theological issues creeping into political discourse. He understood that the question of who is a Muslim would open up a Pandora’s Box where everyone would be fair game, including his own Shia community. He therefore tiptoed carefully around Iqbal’s ideas which he disagreed with, never endorsing them.

The All India Muslim League itself had utilised Allama Iqbal selectively. They had pointed to his address in Allahabad in 1930 as having laid the foundations of Pakistan. On his part, Iqbal had realised the importance of winning over Jinnah and had written a series of letters in 1936 and 1937 asking Jinnah to take up the cause of Muslims in North-West India and to ignore Muslim minorities in the rest of India.

How influential were these letters in Jinnah’s eventual transformation from ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity to an apostle of Muslim separatism, is a matter for a historian to determine. What we do know, however, is that these letters were long forgotten until Muhammad Sharif Toosi chanced upon them in Jinnah’s personal library. When these were published in the 1940s, Jinnah wrote in the preface that he had not saved his replies to these letters and therefore the famed Iqbal-Jinnah correspondence would remain incomplete. As an amateur biographer of Jinnah, I find it very strange because Jinnah usually saved his replies.

Jinnah in any event was not Iqbal’s first choice to lead the Muslims. They had not seen eye-to-eye during the Round Table Conferences in England. Apparently their relationship was not free of rancour even in the end. Iqbal told Nehru in his last days,

“What is common between Jinnah and you? He is a politician and you are a patriot.” (Nehru mentions this in his book Discovery of India).

These differences are very conveniently swept under the rug by our ideologues who want to concoct the false equation “Iqbal+Jinnah=Pakistan”.

In fact Iqbal has long trumped Jinnah in Pakistan. Pakistan of today, a befuddling religious state that has taken upon itself the burden of spiritual wellbeing of its people is precisely the kind of state Iqbal, the theocrat, had in mind and precisely the kind of state Jinnah, the democrat, wanted to avoid. A great part of the blame, however, lies with Jinnah himself for not having disavowed more clearly Iqbal and his ilk who he took on his fellow travellers in his political struggle to his own detriment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ