A wide smile appeared on his face, and he asked me what city of Pakistan I belonged to. After I mentioned that I was from Lahore, his smile grew even wider as he got teary-eyed. He told me that his family is from Jaranwala (a small town in the Faisalabad district), but they had immigrated to India following the partition in 1947. We spoke for a while as he asked me questions about the place he formerly called home. As he was leaving he uttered the following words,

“Partition nahin honi chahiye thi.”

(Partition should not have happened.)

This was not the first time the de-merits of partition crossed my mind, but it was a moment that raised countless more questions.

India and Pakistan both celebrated their 69th year of Independence in the last few days. Almost a quarter of a century has passed and the political and military leadership of both countries remain at loggerheads. The question isn’t whether foreign relations between India and Pakistan are good, it is whether the foreign relations between both countries will remain in the ‘manageable hostile’ zone. The problems between the countries are well documented and don’t need repetition – from water disputes to the murky business of intelligence agencies, the countries take two steps back for every step that has been taken forward. An abundance of economic and military resources are allocated to ensure that the hostile neighbour remains in check.

But despite the hostile attitude towards one other on a federal level, the average Indian and Pakistani connects effortlessly. There are no politics. No religion. No Jinnah. No Gandhi. No Bhutto. No Nehru. There is only the ease of familiarity; the ease that comes with being in a place where you’re surrounded by people who share the same socio-cultural history, and practice the same traditions. Therein lies comfort.

There is something quintessentially South Asian that breaks down borders and creates ease.

Why then, do India and Pakistan remain in a perpetual state of hostility at a federal level?

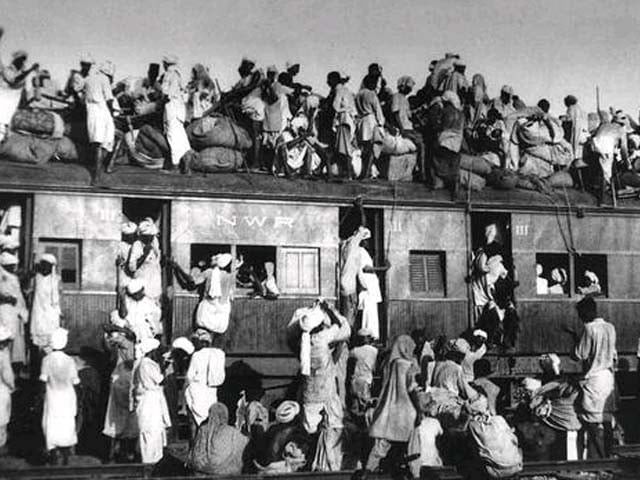

In my opinion, time has shown that the Two-Nation Theory was flawed. Less than 30 years into Independence, Pakistan lost its eastern wing. In no way is this a question of Jinnah’credentials as a statesman of the highest order, but rather, an acknowledgement that an unnatural geographic division based on religious grounds was bound to have problems sooner or later. While the situation in British India before partition was hostile, in hindsight, a united India might have dealt with the problems better. Partition only multiplied the problems by two, with the added horror of mass bloodshed on either side.

As things stand currently, India and Pakistan both have their unique set of challenges, large chunks of which are exclusively linked to the hostile foreign relations between them. India’s involvement in the insurgency in Balochistan is common knowledge, whereas Pakistan’s involvement in the insurgency in Kashmir is also well documented. India has historically gained mileage with political groups in Karachi, whereas Pakistan was actively supporting the Khalistan Movement in the 1980s. The red corridor in India continues to experience Naxalite-Maoist insurgency, with Pakistan having been accused of subsidising it. Similarly, Pakistan has blamed India of supporting terrorist groups active in the country today. India, despite being on its way up economically, suffers from massive levels of poverty and malnourishment. Pakistan is in a significantly lower position economically, and it suffers from problems such as illiteracy and poverty as well. Notwithstanding these glaring problems, both countries allocate significant chunks of their resources on activities aimed at weakening each other.

Both countries remain crippled by the narratives built around memories of the crimes of partition, as politicians (particularly in India) and the military (particularly in Pakistan) continue to fan the hatred of 1947 for their own interests. But in spite of that, it is pertinent to remember that the division of what is modern day India, Pakistan and even Bangladesh, is chillingly unnatural. The communities that were divided in 1947 had coexisted for almost a millennium and, after the British made an exit, a united India would have been better equipped to deal with its problems.

If one wishes to celebrate Independence Day on August 14th and 15th, then celebrate independence from the British – not from each other.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ