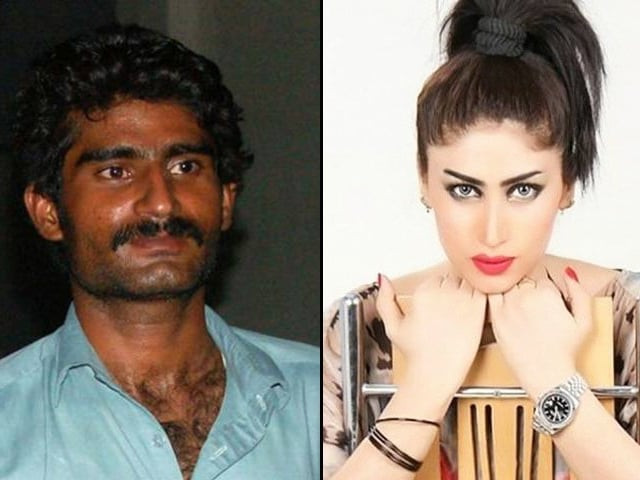

One of Qandeel Baloch’s most important legacies will remain her defiant and glamorous take down of patriarchy through her bold and feisty performances. In the aftermath of her brutal murder, there has been renewed debate around the law against honour killing and its intersection with the laws of Qisas and Diyat.

Many Pakistanis are deeply concerned about laws that bypass legal process for a problematic and potentially arbitrary settlement (and that too) for the most heinous of all crimes – murder or a murder for honour. Even more so, people are concerned that this case will hit trial, will end up forgotten by fatigued activists, and a few years down the road, the court will quietly usher in forgiveness from the father.

The controversial provisions which allow such settlements come from the Qisas and Diyat Ordinance (1990) – which became an act in 1997 under Nawaz Sharif – and are now part of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). These laws permit killers to be acquitted when a victim’s family compounds or settles the case for consideration or waives their rights to have the killer punished through forgiveness without consideration. (PPC 309 and 310)

The government’s decision to ‘bar’ Qandeel’s family from pardoning her killer(s) is a positive step, but it may not be necessarily legal and may have been an exercise of super discretion to prevent settlement and restore public and international faith that Qandeel will receive justice.

Qisas is retributive or equivalent punishment and defined in the PPC as punishment by similar hurt and in the case of murder (or qatl-i-amd), this would be death. Diyat is blood money. A wali or the victim’s heirs (determined through personal law) are entitled to claim Qisas. Alternatively, they may choose to forgive or settle the case against the convict. This undermines the writ of state to punish killings; serious crime is something the state should exercise exclusive prosecutorial control over. These laws, however, reflect our mish-mash of a legal system that started based on colonial law and gradually had Shariah Law interwoven into the PPC, albeit with deeply politicised ulterior incentives.

While the UK was reforming its laws, if imperfectly, to be more just and accessible to minorities, women, and crime victims, weeding out discriminatory sections – our social justice movement was responding to and protesting swathes of law, written in less than democratically, that profoundly undermined women’s rights. It was only in the decade between 2004 to 2014 that a combination of allies – feminists, NGOS, lawyers and female parliamentarians – came together to actually get progressive laws on the books, often dubbed as Pakistan’s pro-women laws.

Parliament made significant amendments to the law regarding killings done in the name of false honour in 2004. Sections 305 and 311 of the PPC currently allow some exceptions to settlement. Section 305 states that the convict or the accused cannot be a wali in case of murder committed on the pretext of honour. This raises a paradoxical question: Why would the law permit a person convicted or under trial for a compoundable crime (other than honour killing) to be a wali at all?

Another significant 2004 amendment is found in Section 311 which states that when all walis do not agree to waive or compound Qisas, then the state may still punish the offender under Ta’zir. As an example, if a victim has four walis, and three of them agree to settle the case in exchange for property, and one does not, the court still retains authority to punish the offender. Thus, one dissenting wali could ensure that the offender is prosecuted, punished and not acquitted through private deals.

Section 311 also explains the principle of fasad-fil-arz (aggravating circumstances) and provides discretion to a court to punish a convicted person under Ta’zir based on past conduct of the offender, their previous convictions, or if the offence is committed in a brutal or shocking manner, is outrageous to the public conscience, if the offender is considered a potential danger to the community, or if the offence has been committed in the name or on the pretext of honour. Honour crime is defined simply in the code as an offence committed in the name or on the pretext of karo kari, siyah kari or similar other customs or practices

Quite appropriately, Section 311 is the subject of discussion and seeing its day in the press. It is an important section and may be the one the court uses to ensure that Qandeel Baloch gets proper justice, and that her brother Waseem is punished irrespective of private pardons. However, there are so many problems with Qisas and Diyat laws, and in fact the whole criminal justice system, including its overly punitive schedules and prescription of the death penalty for 27 offences, that one cannot really celebrate that the government has decided to write PPC 305 and 311 in her FIR.

One such example is PPC 306 which disallows Qisas punishment for fathers and grandfathers who kill their children and grandchildren. It is illogical to advocate that all murders motivated by false honour be non-compoundable and ignore 306. This provision gives informal legislative approval to the very foundation of honour in society. By according patriarchs of the family, this is a legal cover to kill and command a lethal form of obedience in a traditional family. This semi forgiving attitude (they can still be punished up to 14 years or agree on Diyat) gives the message to society that even our laws partially condone certain familial murders.

Shouldn’t all murders be treated equally and be non-compoundable?

Rather than having a few discretionary grounds under PPC 311, Parliament could reform the law on murder, make it impossible to settle across board, and base sentencing on the seriousness of the killing whether it involved conspiracy or pre-meditation, whether the victim was detained or tortured, or killed for racial, ideological, religious or misogynist motives. Honour requires eventual erasure from our social conditioning and needs special attention. Starting with honour murders, our legal community should eventually rally to make all murder an exclusive matter of the state with a multi-faceted public interest campaign around the seriousness of honour killing.

Our case law has colourful examples of Qisas and Diyat law in action – court blessing the exchange of agricultural land for a life, reviewing the decision of families and local notables about a Diyat’s genuineness, dismissing an agreement because one adamant uncle (wali) who refused the killer forgiveness, while his less than principled children compromised. This highlights one of the most obvious criticisms of the Qisas and Diyat law. One killer may settle and walk; the other, with a similar or less egregious crime, may be hanged.

The constitution and human rights conventions require equal treatment for all; yet the law permits grossly unequal treatment of murderers depending on their socio-economic background relative to the victims, the power of jirgas and tribal customs, and the status of victims in various communities. Who are we to place values on lives – be it a Thari woman, a Gujjar from Mansehra, a Saraiki rights activist. Qisas/Diyat, however, laws perpetuate embedded inequities in the political landscape.

The revival of the death penalty in Pakistan further complicates the debate for people who are rightfully opposed to it as a draconic and possibly unjust punishment, given the numerous errors in investigation and procedural miscarriages. A murderer would get reprieve from a draconian sentence, but through erroneous private justice. And if all murder becomes non-compoundable and walis can’t strike deals, the court would freely exercise its exclusive power and sentence people to death in most cases. This leads to the whole scheme of harshly punitive justice in Pakistan that often exposes the deep contradictions that rights activists must address – we want justice for an honour crime and an end to violence against women, yet support of capital punishment and decades in prison (including under trial) violates norms of human rights.

Even the seemingly benevolent provisions towards minor and insane offenders are quite onerous and punitive. Qisas punishment is disallowed for a minor or an insane offender; nevertheless, PPC 308 allow a Tazir sentence of up to 25 years if it is proven that the insane person killed during a period of lucidity or the minor had gained sufficient maturity.

Would justice be served if Waseem serves time in jail rather than be lauded as a hero avenging a false honour?

Certainly.

Would justice be served if extended families and punchayats able to pressure her father to forgive are prevented from doing so?

Certainly.

Would justice be served if Waseem is executed, after a protracted trial of four years, and decades in prison?

Maybe, not.

He may be the principal killer, but there have been a series of aiders and abettors who incited hatred, fuelled passions against her, chastised, berated, ridiculed her, revealed her personal data, and then later rejoiced at her death. They will go scot free. They will then applaud Waseem’s hanging because their hatred and misogyny toward Qandeel is their utter lack of compassion and their apathy to justice. Long live our sister, Qandeel!

Would justice be served if Waseem is eventually executed? Maybe, not.

We want justice in an honour crime, yet support capital punishment and decades in prison violates human rights.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ