He adds that the “phase of levelling inequality” was cut short quickly by General Zia and a new phase of cornering the wealth of the nation by a few hundred was launched.

He and other left-of-centre writers like to glorify the Bhutto regime – why else would anyone call the six years of economic ruin and destruction “a levelling phase”?

I recently spent some time digging 40-year-old data to find out the actual economic performance of the Bhutto regime. I made a point of taking no help whatsoever from the internet. I relied mainly on the central library of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Karachi.

I got all the statistics and economic commentary from annual reports of the SBP, economic surveys, annual plans, official gazettes and other authentic government sources.

Before I note down my key findings, let me share with you a titbit that reflects economic management under the Bhutto regime: in an unprecedented move, the Bhutto government had “withheld” the publication of the annual reports of the SBP for three consecutive years — 1973-74, 1974-75 and 1975-76. That was because the central bank was critical of Bhutto’s economic policies. These reports were later released only for the publication in the official gazette.

Disclaimer: I took the following notes from half a dozen sources (all authentic though). But I have not rephrased each and every sentence and properly cited every detail. That’s because it’s not academic or even journalistic writing: this blog post aims to help people get a gist of Bhutto’s economic management.

A lot of statistics are from the white paper on the state of the economy published by the subsequent military regime. Its commentary is indeed biased, but statistics are from the national accounts and hence undisputed. I have also taken help from Shahid Javed Burki’s book, “Pakistan Under Bhutto”.

Another book, “Public Enterprises in Pakistan” by Robert LaPorte and Muntazar Bashir Ahmed was of great help with regard to understanding the post-Bhutto privatisation process.

Happy reading…

- Although the reported GDP growth rate for the five-year Bhutto rule (1972-77) was 4.16 per cent, the overall growth rate was “puffed up” because of 1972-73 — the first fiscal year of the Bhutto regime that witnessed a rebound in economic activity from the depressed war level of 1971-72.

- Excluding 1972-73, the average growth rate for the Bhutto years comes down to only 3.48 per cent per annum for the four years i.e. 1973-74 to 1976-77. The population increase over the same period is estimated to be three per cent per annum. As a result, the growth in per-capita income was less than one per cent per annum.

- Even the nominal growth in national income during those years did not originate from productive sectors like industry and agriculture. So-called growth emanated from the services sector because of the large, unproductive expansion of jobs in the public sector.

- The commodity producing sectors – industry and agriculture – grew at two per cent and 2.9 per cent per year, respectively. The two sectors contributed only 28.5 per cent of the cumulative increase in the GDP during the five-year period, ending June 1977.

- In contrast, the economy had grown at an average rate of seven per cent per annum for the 1960s, with per-capita income growth clocking up at a healthy 3.8 per cent per year.

- Owing to a rapid increase in prices, export growth in nominal terms for the period following 1972-73 was 7.2 per cent per annum. However, there was a net decline in the real volumes of exports over the Bhutto years. Pakistan’s share in world exports declined from 0.16 per cent in 1972 to 0.12 per cent in 1976.

- Inflation equalled 17.3 per cent per annum during 1972-77. While the government tried to blame it on the global energy crisis in 1973-74, global statistics show Pakistan’s inflation rate was significantly higher than the average for Asian countries (11.6 per cent) for the same period.

- The balance of payments deficit on current account jumped 795 per cent during Bhutto years — from $100.8 million in 1972-73 to $902.5 million in 1976-77.

- Most of the deficit was financed by external borrowing. Outstanding external debt more than doubled to $6.3 billion between December 1971 and June 1977.

- The net external borrowing in five years of the Bhutto regime was equal to the total borrowing in the previous 25 years.

Industries

- Bhutto assumed power on December 20, 1971. On January 1, 1972, the government took over 31 industrial units under 10 categories of industries.

- The nationalised industries included shipping, iron and steel, basic metal, heavy engineering, assembly and manufacturing of motor vehicles, tractor plants, chemicals, petro-chemical, cement, and public utilities, including electric generation, gas and oil enterprises.

- The nationalised companies were put under the management of the Board of Industrial Management (BIM).

- The categories were defined vaguely, so that it was possible to take over some units and leave out others. This was particularly true in the light engineering sector where small units belonging to political opponents were taken over while much larger units were left untouched.

- No assessment was made of the nature of the units which were selected for nationalisation. Some of the units were already making huge losses. Taking over these sick units heavily burdened the public sector and was a drain on its resources from day one.

- Initially, the government order was to “take over the management” only while ownership was left with original owners.

- In August 1973, however, rules were amended to acquire a majority share ownership “on compensation” of the taken-over units. In November 1973, orders were issued for acquiring majority ownership in the public limited companies and the entire equity of the private limited companies. In March 1974, rules were again amended to provide for payment of compensation for the acquired shares at market value instead of the break-up value as envisaged earlier.

- Originally, there was no mention of compensation. Later, a compensation formula was given, but the principle of adequate compensation was never accepted.

- In 1972-73, BIM units employed 40,817 people, but the number went up 64,643 people in 1976-77, up 58 per cent. But production did not increase correspondingly, with labour productivity declined in a majority of units, according to government statistics.

- Salaries, wages and other benefits for the BIM as a whole increased over 322 per cent between 1972-73 and 1976-77.

- Despite the increase recorded in sales numbers (in nominal terms because of price increases), net earnings were negative on large capital invested in these undertakings. Among the industrial units, profits were available only in the cement sector where repeated price increases were introduced.

- A number of industrial units were set up without economic consideration. A notable example is the sugar mill set up by PIDC in Larkana. PIDC had pointed out that a sugar factory in Larkana may not be viable, as Larkana was not a cane-growing area. The cane had to be supplied to the factory from a distance of 150 miles. It was established nonetheless and had incurred a loss of nearly Rs20 million in the first two years of its operation.

- In October 1977, the military government appointed a commission to review the financial position of state-owned enterprises. The commission reported that only 15 out of 54 units were in a position to maintain profitability in 1972-77.

- Reviewing the cumulative position of the entire Bhutto years, the commission report said net accumulated losses for the 54 enterprises taken together was Rs320.9 million.

- The commission report said the labour productivity declined in 39 out of 54 units.

- The commission reported that 30 of these units were operating on an average below-70 per cent of installed capacity. Between 1972 and 1977, capacity utilisation had declined in the case of 21 units.

- At the end of 1977-78, there were 12 BIM units that had a negative net worth compared to only two units in 1970-71.

Agro-based industries

- Between 1972-73 and 1976-77, the agriculture growth rate was two per cent per year as opposed to 6.4 per cent per year recorded throughout the 1960s.

- Although its manifesto did not promise it, small agro-based industries were also privatised for simple processing of agricultural produce in the rural areas. In July 1976, the government announced it had taken over cotton ginning, rice husking and large flour mills throughout the country, with exemption granted to units with foreign participation.

- Initially 2,815 units were nationalised under this policy. These included 578 cotton ginning units, 2,113 rice husking units and 124 flour milling units.

- In May 1977, however, 1,523 small rice husking units were returned to their owners.

- To handle the nationalised units, Cotton Trading Corporation, Rice Milling Corporation and Flour Milling Corporation were set up in addition to the establishment of a separate Ministry of Agrarian Management.

- In 1976-77, the Rice Milling Corporation operated units that constituted only two-thirds of the nationalised rice-husking units. In both quantity and quality the corporation did not achieve any major objective. Thus the loss suffered by the corporation amounted to Rs200 million in 1976-77.

- As for Cotton Trading Corporation, it managed to operate less than half of the nationalised ginning units. It was largely used as a source of unproductive employment, as its number of workers almost doubled in just one year.

- Uncertainty prevailed for the whole of 1976-77 about the exact number of units nationalised. The list included pieces of land that displayed a signboard of “under-construction”. Residential houses were also nationalised if the owner had found it convenient to install machinery in one part of his large rural compound. Cattle, poultry and fish ponds were also nationalised if they were on the premises of the factory.

- In one case, a primary schoolteacher was appointed a factory manager, as the government had to quickly mobilise personnel without due scrutiny. In another case, an Inspector in Market Committee of Thari (Tehsil Mirwah, District Khairpur) was appointed deputy manager on the orders of a minister.

Vegetable ghee

- The government took over the vegetable ghee industry in September 1973, although it was a small consumer goods industry with a total capital investment of Rs200 million at the time of the takeover.

- In the three years following the nationalisation of this industry, number of workers employed increased by one-thirds. Mismanagement resulted in aggregate losses of Rs24.3 million and Rs29.4 million in 1974-75 and 1975-76, respectively.

Price increases

- One of the rationales for nationalisation, according to the government, was to ensure stability in the prices of everyday use. However, history shows prices rose faster than they increased in the preceding decade.

- The retail price of Zeal Pak Cement increased from Rs151.5 per ton in February 1972 to Rs443 per ton in June 1977, an increase of 192.7 per cent over five years.

- The retail price of sugar increased from Rs1.60 per seer in 1972-73 to Rs4 per seer in 1976-77, signifying an increase of 775 per cent in four years.

- The price of vegetable ghee increased from Rs6 per seer in 1973 before nationalisation to Rs9 per seer by 1977, up 50 per cent in four years.

- Big price increases took place in industrial items as well. The price of rolled material increased from Rs2,000 per ton in 1972-73 to Rs5,025 per ton in 1976-77, up 151.25 per cent in four years.

Private-sector industries

- After the nationalisation of 31 concerns in January, 1972, the government declared an end to the nationalisation process. However, in September 1973, it took over vegetable ghee industry. This was followed by the nationalisation of banks and shipping industry in January 1974.

- Banks’ nationalisation on January 1, 1974, occurred within 24 hours of a meeting (held on December 31, 1973) in which Prime Minister Bhutto told private-sector representatives in Karachi that nationalisation would not take place anymore. The government nationalised the banking sector except foreign banks, without consulting the SBP.

- Then the government took over the marketing and distribution of petroleum products.

- In 1976, cotton ginning, rice husking and flour mills were also nationalised.

- Prime Minister Bhutto had openly vilified entrepreneurs and businessmen in these words:

“The business community is continuing to take part in activities prejudicial to the government. We must put an end to these so-called businessmen’s moots. Each of the individuals who participated in this meeting should be watched carefully and we should have a complete dossier on every one of them to be able to put them on right track.”

Sharp fall in investment

- According to 1975-76 Annual Plan released by the Planning Commission, the (private) industrial investment at Rs576 million in 1973-74 was less than half the level in 1969-70 even in money terms.

- As a result, large industrial families started moving out of Pakistan with whatever they were left with. The Dawoods moved to Texas, United States, the Saigols started investing in the Middle East and the Habibs focused on Europe for growth opportunities.

Textiles

- Between 1972-73 and 1976-77, the export volume of both yarn and cloth declined. One of the reasons was frequent revisions in export duties of these items. Between May 1972 and June 1974, the duty on yarn was changed as many as eight times. The duty on cloth increased on seven different occasions over the same period.

- At the end of 1976-77, about 0.9 million spindles out of a total 3.507 million were out of operation, with about 12,000 looms also closed.

- The productivity of labourers in the textile industry in Pakistan between 1971 and 1975 kept declining at an annual rate of four per cent, according to a survey by the Cotton Textile Industry Research and Development Centre, Karachi.

Zia regime and denationalisation

- Upon taking over the government, General Ziaul Haq immediately reversed the nationalisation process initiated by the Bhutto regime. Zia denationalised around two thousand ginning mills that Bhutto had nationalised.

- He tried to denationalise other state-owned enterprises as well but remained largely unsuccessful for a variety of reasons listed below.

- In the book titled Public Enterprises in Pakistan by Robert LaPorte and Muntazar Bashir Ahmed, the writers state that the government became fed up with the private sector because it had not acted “in good faith” with regard to denationalisation.

- The law required that previous owners enjoyed first priority in terms of purchase from the government. However, the previous owners of the nationalised firms offered for sale wanted several conditions that the government was unwilling to grant. Such conditions included purchases prices below market rates partly because the companies were now overstaffed and the labour was unionised.

- Another condition demanded by the previous owners was the continuation of the “privileges” that the nationalised units had as public enterprises, such as credit on concessional terms, subsidised inputs (gas/oil/electricity), and continuation of price controls.

- The previous owners of the nationalised enterprises also demanded changes in labour policy that would allow them to get rid of surplus labour.

- In addition, the private sector was not particularly interested in acquiring the old public enterprises because private investors would rather develop new concerns that would not be fettered by debt, overstaffing and out-dated equipment.

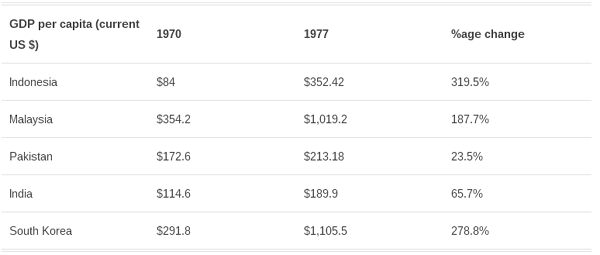

- Here’s a snapshot of Pakistan’s growth in terms of GDP and GDP per capita under the Bhutto regime. It’s evident that Pakistan recorded the slowest growth in each category compared to Indonesia, Malaysia, India and South Korea during the period under review.

If the following two charts don’t convince you how disastrous Bhutto’s economic policies were for Pakistan, then I don’t know what will.

This post originally appeared here

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ