I fell in love with cricket because of our legendary fast bowlers

We no longer have role models in the team like we used to, thus no one is capable of motivating the young lads.

Fast bowling is obsolete now. This phrase is difficult to comprehend for every cricket enthusiast of my generation. Honestly, it was the deadly fast bowlers of our country that made us fall in love with the beautiful game of cricket, in the first place.

No doubt fast bowling has always been Pakistan’s trump card. We had the best pace attack in the history of cricket spearheaded by the great Imran Khan in the 80s, Wasim Akram-Waqar Younis in the 90s and the speed star Shoaib Akhtar in early 2000s. This trio was one of the most celebrated lots of fast bowlers in the history of the game. They were lions – fighters under all conditions.

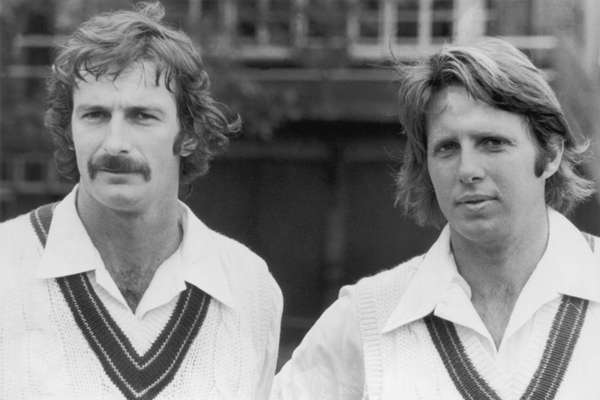

Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, he best fast bowling pair of all time in subcontinent!Photo: Google Plus

Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, he best fast bowling pair of all time in subcontinent!Photo: Google PlusLooking at the stats of the great Khan, he had a magnificent record as a fast bowler in the 80s. His unparalleled average of 19.12 in Test cricket left Caribbean greats such as Michael Holding, Courtney Walsh, Joel Garner and Malcolm Marshall, along with the Aussie legend, Dennis Lillee in the background. He inspired a generation of youngsters in Pakistan to become fast bowlers. The 90s were one of the most competitive years for cricket and can rightly be termed as the decade of bowlers.

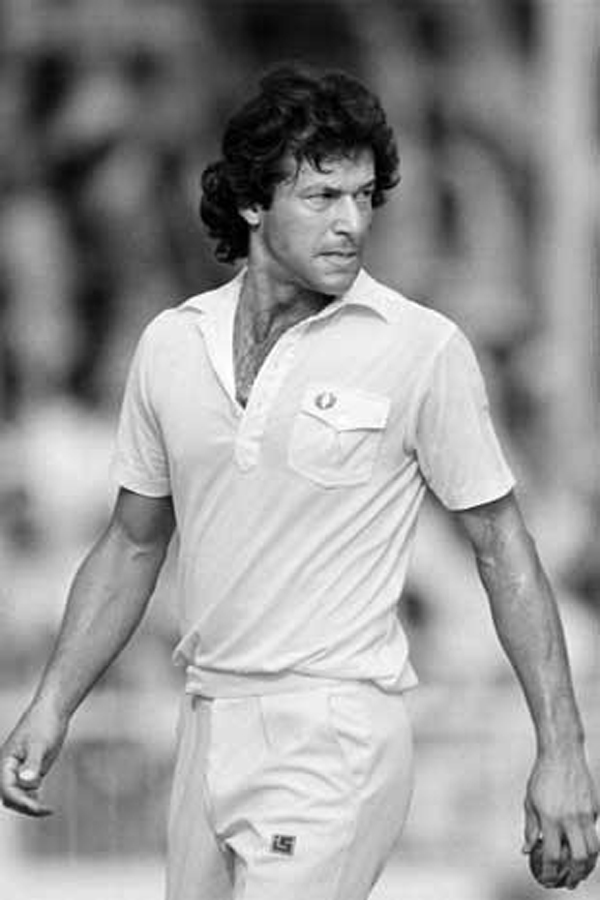

Imran Khan - The Lion of Pakistan : he was Pakistan's most successful cricket captain, leading his country to victory at the 1992 Cricket World Cup, playing for the Pakistani cricket team from 1971 to 1992, and serving as its captain intermittently throughout 1982–1992Photo: David Munden/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Imran Khan - The Lion of Pakistan : he was Pakistan's most successful cricket captain, leading his country to victory at the 1992 Cricket World Cup, playing for the Pakistani cricket team from 1971 to 1992, and serving as its captain intermittently throughout 1982–1992Photo: David Munden/Popperfoto/Getty ImagesWasim and Waqar, successors of the great Imran Khan, brought new dimensions to fast bowling by introducing fresh strategies, ploys and putting the reverse into swing. The duo bucked the Windies’ and Aussies’ trend of pitching fast and short by pitching fast and full. They breathed life in the dead pitches. Above all, they reminded everyone that fast bowling was supposed to be just that – fast.

Portrait of Pakistan fast bowlers Wasim Akram (left) and Waqar Younis during the Third Test match against the West Indies at Gaddafi Stadium in Lahore, Pakistan. The match ended in a draw. (December 06, 1990)Photo: Pascal Rondeau/Allsport

Portrait of Pakistan fast bowlers Wasim Akram (left) and Waqar Younis during the Third Test match against the West Indies at Gaddafi Stadium in Lahore, Pakistan. The match ended in a draw. (December 06, 1990)Photo: Pascal Rondeau/AllsportIn my opinion, bowling strike rates are of greater significance in Test cricket than in ODIs. This is because the primary goal of a bowler in Test cricket is to take wickets and get the opposition out twice during a Test match, whereas, in an ODI, it is sufficient to bowl economically.

In this particular context, if you were to compare Waqar and Shoaib with former legendary bowlers such as Lillee, Thomson, Marshall, Sir Richard Hadlee – Burewala Express and Rawalpindi Express would leave these legends behind, owing to their remarkable strike rate in Test matches, with 43.4 and 45.7, respectively.

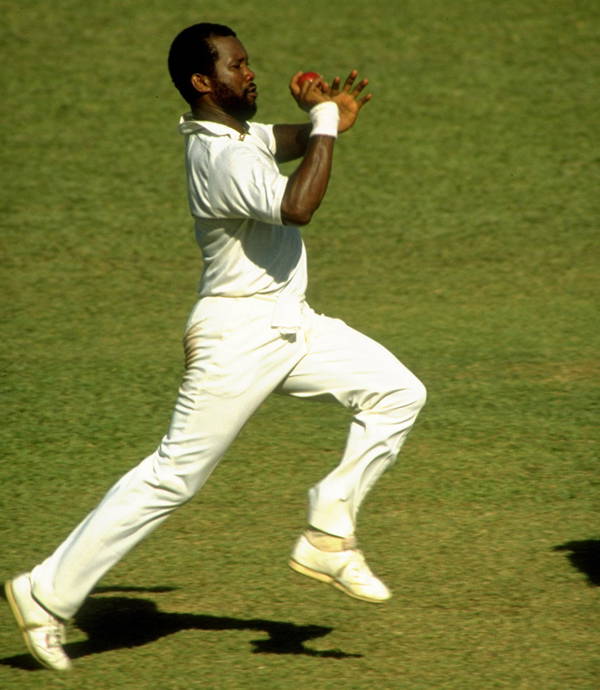

Australian cricketing heroes Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson (pictured together in 1975)Photo: Getty Images

Australian cricketing heroes Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson (pictured together in 1975)Photo: Getty Images Malcolm MarshallPhoto: Ben Radford / Getty Images

Malcolm MarshallPhoto: Ben Radford / Getty Images Great all-rounder Richard Hadlee played with his elder brothers in the 1975 World Cup against England.Photo: Getty Images

Great all-rounder Richard Hadlee played with his elder brothers in the 1975 World Cup against England.Photo: Getty ImagesWinston Churchill would have described the lack of quality in the department of fast bowling (in spite of our glorious past) as a “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” One probable reason is that we no longer have role models in the team like we used to, thus no one in the Pakistani crew is capable of motivating the young and determined lads.

In the past, it wasn’t the coaches but the senior players in the team who mentored and nurtured young players. Shoaib Akhtar’s brilliant run-up and lethal bowling is not due to the coaches, rather inspiration from senior players. In fact, various coaches recommended that he cut short his run-up, which would enable him to prolong his career.

If you look at the current bunch of Pakistan’s fast bowlers – barring Mohammad Amir, I honestly don’t see any one who puts himself out there with a certain plan in mind.

Amir is in a league of his own. What I admire the most about him is his phenomenal ability to swing the ball so that the delivery to the right-handed batsmen is delayed. You rarely see such stuff.

He smoothly approaches the stumps without a clown jump, (like Junaid Khan) nears the stumps, and since his wrist is firmly behind the ball, it tails back in sharply. In addition to that, he consistently tries to pitch full, invariably clocking 145 kph.

We certainly have high expectations from him and he has been extremely fortunate in getting a second chance. He may still have the potential of becoming one of the greatest bowlers in the history of Pakistani cricket. However, as we have seen with the likes of Mohammad Zahid, Shabbir Ahmed and Mohammad Sami – potential or talent alone does not guarantee greatness.

Mohammad AmirPhoto: Reuters

Mohammad AmirPhoto: ReutersIf the art of fast bowling is to survive in the future, the International Cricket Council (ICC) needs to treat fast bowlers on the same level as batsmen. You need pitches where bowlers are able to take 10 wickets. You need bowling heroes in the game, where young boys can look up to them and say,

“I want to bowl fast just like him.”

If you compare the bowlers of the 80s and 90s with the fast bowlers of now, there are only two genuine fast bowlers; Dale Steyn and Mitchell Starc. But If the Indian Premier League (IPL) is all about getting two million dollars for hitting the ball out of the ground, then who wants to bowl fast?

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ