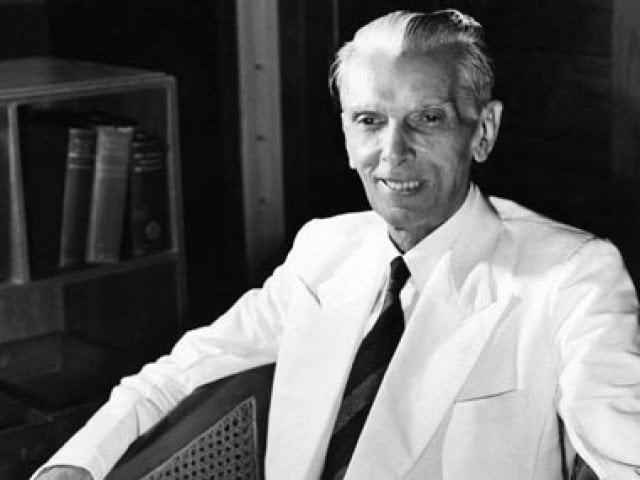

In a poignant piece for Granta sometime ago New York Times journalist Jane Perlez pointed out that one’s choice of Jinnah portrait could tell a lot about one’s ideological affiliations in Pakistan. But what was Jinnah’s own ideology? Was he a liberal or a conservative? Which of the two bar rooms would he sit in if he were here today?

His background and training gives us a clue. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam and the founding father of Pakistan, was born into an Ismaili household as Muhammadali Jinnahbhai, though he became a Khoja Ithna Ashari Shia in 1901 after the Agha Khan refused to bless his sister’s marriage outside the Ismaili community.

Earlier he had changed his name to Muhammad Ali Jinnah while at Lincoln’s Inn in 1892 arguing that the suffix “bhai” was rudimentary because in his view “bhai” and “mister” were interchangeable. Like all barristers, however, he was most commonly referred by his peers as “Jinnah” or “Mr Jinnah” depending on who addressed him.

His time at the Bombay bar suggests that young Mr Jinnah identified himself first and foremost as a modern Indian. To him most religious practices were either meaningless rituals or useless superstitions. Dietary restrictions were summarily rejected by him. From all accounts he ate and drank at Bombay’s finest eateries like Cornaglia’s Restaurant. These eateries did not serve halal food and that did not seem to bother him in the least. Indeed he was the embodiment of Macaulay’s ideal Indian, an Indian by skin and name but an Englishman in tastes and habits. From his time in London, he also imbibed the best that British liberalism had to offer, rejecting racial distinctions and tribal associations as relics of the past.

His commitment to this British brand of liberalism was so strong, that he was amongst the earliest supporters of the Suffragette Movement in Britain.

The left leaning bar room has a photograph of an emaciated Mr Jinnah in a suit.Photo: Jinnah Blog post

The left leaning bar room has a photograph of an emaciated Mr Jinnah in a suit.Photo: Jinnah Blog postFor a decade and a half, Jinnah was Bombay’s most eligible bachelor and its leading politician. In 1918 he, in the immortal words of Sarojini Naidu, plucked the blue flower of his desire. Ruttie Petit, the daughter of Parsi magnet Dinshaw Petit, had to convert to Islam. This had to do with the law which required, in the event of an inter-communal marriage, either renunciation of faith by both parties or conversion by one.

Jinnah, by now elected on a Muslim constituency, had to retain his religious identity. It was well known, however, in Bombay’s circles that Ruttie Jinnah’s conversion to Islam was merely in name. Instead of becoming a Muslim wife, Ruttie freely dabbled in theosophy and even delivered lectures on it in Duke University in the US.

Meanwhile her strapless dresses often created scandals. On two separate occasions, Jinnah walked out with his wife, after a host chided Ruttie for wearing strapless dresses. Once was at a dinner with Lord and Lady Wellingdon. The second was when the Begum of Bhopal told Ruttie that she was a Muslim now and that she should dress accordingly. Jinnah’s reaction on both occasions is instructive.

Politics often decides its own course. Jinnah’s politics continuously evolved from 1906 when he joined the Congress to the time he took office as Pakistan’s first Governor General. Much has been written about it. There is no dispute, even amongst his worst critics, that from 1906 right up to 1937, Jinnah’s politics were completely secular.

During this period he saw himself as an Indian first, second and last and was unwaveringly committed to the ideal of a united and independent India. It was only after 1937, after failing to secure an equitable power sharing arrangement with the Congress in UP, that Jinnah turned his attention to consolidating the Muslim community as a voting bloc. It is a fact that even when Jinnah took up the Muslim cause, his idea of Islam was informed not by the religious orthodoxy, but by a modernist interpretation of Islam.

This was a time, when the modernists in the Muslim intelligentsia far outnumbered the religiously orthodox. The binary of secular versus religious just did not exist for the modernist Muslims of the Muslim League. This is why for Jinnah there was no contradiction in speaking about Islamic principles of justice and fair play in one speech and speaking of religion as a personal matter in another.

Laws; whether religious or secular, in Jinnah’s estimation could only be drafted, discussed and enacted by modern men and women elected through the ballot. All citizens of Pakistan regardless of their religion or gender would be equal citizens of the new state.

Jinnah made it absolutely clear that Pakistan would not be a theocracy to be run by priests with a divine mission. There was no space for a Council of Islamic Ideology and the Federal Shariat Court in this vision. Nor could he have imagined that one day Pakistan’s National Assembly would decide whether a particular sect is Muslim or not.

Was he a liberal or a conservative?Photo: Pakwheels

Was he a liberal or a conservative?Photo: PakwheelsSo which picture of the Quaid-e-Azam is based on fact? And which is fiction?

General Ziaul Haq’s Islamising government in the 80s actively censored his photographs in suits, his photographs with dogs, and him smoking cigars. Instead the Zia government tried to project him as an Islamic cultural relativist, which was the farthest from what he was.

Take it or leave it but Jinnah was the embodiment of the term “brown sahib”. He smoked, drank and ate as he pleased, all the while dressed in immaculate three piece suits and two tone shoes. As a politician trying to mobilise the masses, he did don the sherwani and karakul for select public occasions but that was an exception, not the rule. When the Islamists and conservatives try to find a puritan and a fundamentalist in Jinnah they are sorely disappointed. This is why they insist on elevating Allama Iqbal, the true cultural relativist as his equal as a founding father.

Nor should left liberals and secularists expect to find a consistent and an ideologically pure secular position in Jinnah’s politics post 1937. He was a great advocate and a master politician but never an ideologue. Jinnah was essentially a liberal and modern man who nevertheless was a pragmatist catering to the idiom of his people.

We must therefore study Jinnah holistically as a great practitioner of the art of politics. We should refrain from retrofitting our own ideologies on him.

[poll id="594"]

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ