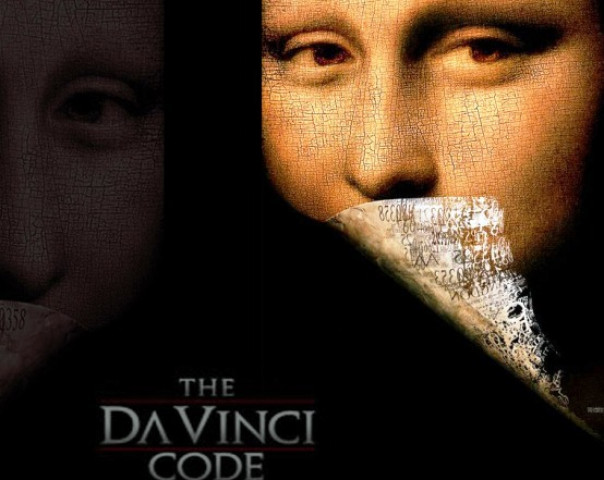

Very few books dig down into the roots of history, challenge your beliefs and provide food for thought; this one did. Besides igniting some ferocious controversies and becoming a global phenomenon, the book established its author, Dan Brown, as a talent to watch.

However, Brown's next books have failed to live up to the standards that he himself modeled. There’s a blatant sense of repetition and a tone of monotony easily palpable in his novels that followed. Take a look at some of the common features that you find in all of his books.

- It’s always about changing the world. The antagonist maliciously claims every other second that the world is about to change forever in a matter of hours, and the protagonist fears this to be true. However, in none of the novels does the world actually change. All that changes in the end are perceptions.

- The novels are invariably based on history. They keep on feeding us on the things that we didn’t even know existed. It’s either about some ancient, secret brotherhood, some thousand years old symbols or some utterly forgotten, dead artists. We would appreciate a lesser dose of history.

- The main character knows absolutely everything, and so does his accompanying female companion. Honestly, is there anything on Earth the couple is blank about? Even in the sequences where they pretend to be clueless about a certain thing on the first glance, the revelation always dawns upon them; sooner or later. How very convenient!

- Agreed, the precise details are the USP of the books, but sometimes it seems as if we are reading Wikipedia instead of a novel. How many of us are actually concerned about the number of stairs in the Washington Monument, or the number and pages of books in the Vatican archives, or the exact height and architecture of the Louvre Museum?

- There’s too much family drama in the novels: estranged parents, lost children, busted relations and stuff. And more often than not, the stories kick off by the death of a character among these. Then, as we can guess, Robert Langdon jumps in to the rescue.

- The stories never span a time limit of more than twenty four hours. During the proceedings, the characters might travel across continents, unearth world’s greatest mysteries and experience all that stuff that we require days even to understand. Yet, they are quick enough to conclude all these mammoth tasks in a mere day.

- The endings are always abstract. They are in direct contrast to the dramatic, majestic endings that we conceive during reading the book. They always tend to go towards a philosophical, safer side; no bombs go off, no secrets are made public, and the rest of the world keeps on sleeping.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ