Earlier this year, there was an attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris; it was a barbaric and detestable attack, and journalists were killed for voicing their right to free speech. Though I must add here that I do not support the kind of journalism Charlie Hebdo endorses; it’s offensive, and at times, plain old repulsive, but people have a right to free speech, however nasty it may be, hence if they publish the morally repugnant and call it satire, they have a right to do it, yes they do.

I recently came across a news story where Charlie Hebdo published cartoons mocking the drowning of the three-year-old Syrian child, Aylan Kurdi.

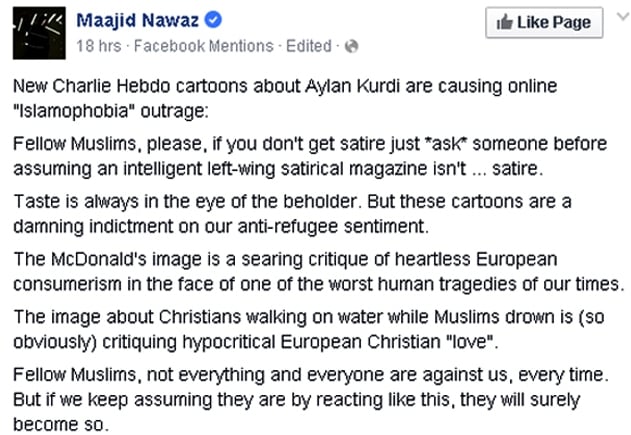

The cartoons at first sight were pathetic, but since many claimed them to be misunderstood satire, I thought I’d give them a deeper look and not just a cursory glance. I did not see anything remotely intellectual or satirical in the sketches. There were mixed reviews on it, both extreme. Many novice and so-called seasoned intellectuals thought it to be a deep satire on European consumerism, while others saw what it actually appeared to be. Following is how Maajid Nawaz, an activist, author, columnist and politician, explained the cartoons:

Sorry Mr Nawaz, but I don’t see it. Maybe I and the rest like me are just not intellectual enough to get this sort of satire. There were countless other ways to show satire marking the Syrian refugee crisis, and/or to bring attention to the tragic death of little Aylan, and the global disregard on the occurrence of this mishap. But this was most certainly not the way to do it. The cartoons were distasteful, disrespectful, and abhorred by many who are cerebral enough to appreciate satire, but not this kind.

Nine months ago, when Charlie Hebdo offices were attacked, many people on social media changed their profile picture to, ‘I am Charlie Hebdo’. Now my response to that would be, ‘No, I was never, and will never be Charlie Hebdo’. In much the same way, I will never be a mocker, or minimise the human tragedy of native Americans at the hands of Europeans, Jews at the hand of the Nazis, 9/11 at the hands of Osama Bin Laden, Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus, Shias, Sunnis at the hands of each other, and repulsive mockery at the hands of Charlie Hebdo.

Satire is a wonderful tool that writers use to explain a social position, but maintaining class and balance is essential when using this tool, especially when handling sensitive issues, such as the tragic death of a baby boy.

Shame on Charlie Hebdo for mocking such tragedies, and shame on us for not setting any boundaries on professional journalism. Political correctness is sometimes just a lie, some things will never be right, simply because they are just so wrong, and mocking dead children is one of them.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ