“Ma’am, he is waiting for you upstairs.”

The first thought that runs through my mind: HE?

There must have been some mistake, I thought.

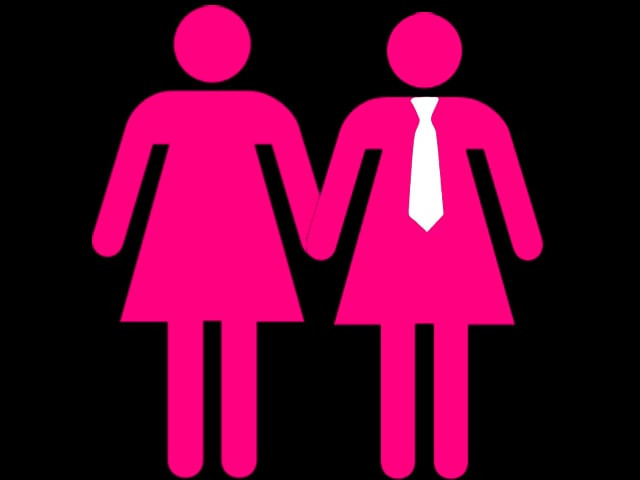

To my surprise, I meet a person I was more inclined on calling ‘handsome’ than ‘pretty’. Surrounded by the strong smell of men’s cologne, she was dressed in a crisp white dress shirt for men, a brown belt and beige trousers. I could see the sweat on her hands that wore a Swatch and carried a Blackberry.

Ariba Rizvi, at the age of three, displayed traits that made her seem like a ‘tomboy’ but weren’t enough for others to accept that she was ‘different’. Having never gone through puberty, this 28-year-old law student, and daughter to a divorced couple in Karachi, realised that her sexual orientation did not fit the norms of our society.

“The first time I had a crush on a girl was on my brother’s girlfriend. I used to hug her and give her flowers from our backyard,” says Ariba.

Today, the classifications are broader than just gay or lesbian. In lesbianism, nature (biological) and nurture (psychological) help classify Ariba’s category into what is known as ‘dyke’. One of her first cousins, whom I met a week before, said,

“Ariba always saw herself as a man. Her dad calls her Mr Pakistan.”

While Pakistan has almost always denied recognising its LGBT community, these ‘coming out of the closet’ moments serves as some form reality check. From rumours of Iraj Manzoor, a supermodel known to be relationship with a young woman, to the marriage of Rehana Kausar and Sobia Kamar in the UK, today the LGBT community is larger than it is assumed to be, with no legal recognition for civil unions at all.

Ariba has about seven such friends with no support groups or camps. She says,

“It’s your fight and everyone fights their own battles.”

Given the religious scriptures and homophobic mind-set, such acts and beliefs are a grave sin, considered haram and punishable. However, Ariba’s stance is similar to lesbian rockstar Vicky Beeching’s, who said,

“God loves me just the way I am.”

Ariba says praying five times a day keeps her close to God and she sees this as His choice.

“For me, I just need my God and I don’t need to care about the rest.”

In a deep voice and at a slow pace, she tells me about her horrors from medical check-ups to being force fed pills and having suicidal thoughts.

Choking up, she said,

“My parents aren’t understanding, rona dhona (crying), phadday hotay hain (there used to be fights). It’s frustrating. There comes a point when you say main kia karoon (what should I do)? There’s your family on one side, which you love so much, and then there’s the fact that you can’t lie to yourself.”

She says that she was forced to restrict her social life to interests like poker and sports because of her family.

“I don’t want to embarrass my parents.”

To me, Ariba’s take on life seemed more rational than emotional. She says most of the people around her mistake her for a man and call her ‘Ahmed’. But she never compromised on her looks, even when people stared and laughed.

Not being able to fathom the idiocy of those who judge her, she said,

“How can people say it’s in your head? How stupid do you think the other person is that he would give up his life because of something that’s in his head?”

When you’re a woman, the thoughts of romance, love and other fantasies are common to you. To my surprise, Ariba wasn’t new to the dating world and the pool of prospects was enough for her to have had 40 relationships, all with straight women.

When asked about loyalty, she said,

“Yes, I’ve cheated once or twice.”

But for Ariba, the continuous sense of insecurity is over the fact that a girl she’s with can choose to be with ‘real men’ and leave her.

She moved the conversation to financial independence and said she had been investing in business ventures because she realises that her sexuality could be an obstacle if she were to go job hunting. Ariba plans to have a family of her own in the future. She plans to undergo a sex change surgery within the next three years so she can marry the love of her life.

When I asked her, hypothetically, about having to raise a homosexual child, she flinched and said,

“If it’s a condition, woh Allah se hai (it’s by Allah). I’m not a part of it in any way.”

During those 70 minutes of the interview, I kept trying to put myself in Ariba’s shoes, trying to understand her perspective, but with all the taboos attached to such a discussion, let alone such a person, in Pakistan I felt hopeless and helpless. Fidgeting with her keys, she said,

“There is no solution, it can never change. It keeps on hitting you and you become stronger...”

And then I saw it, a lot of strength, courage and the slightest glimmer of hope.

Names have been changed to protect identities.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ