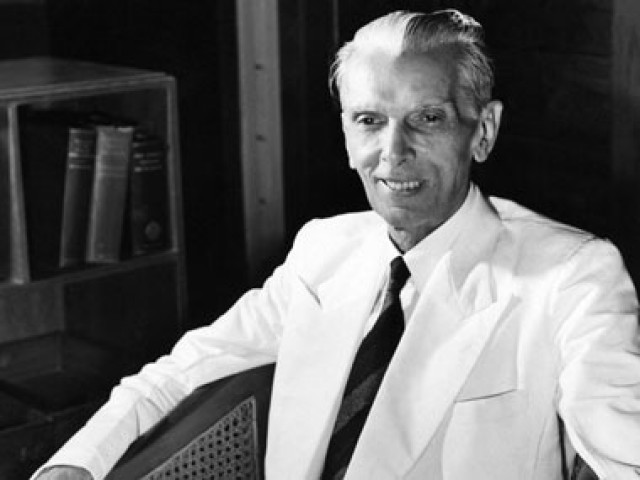

“I thoroughly endorse the principle that while this measure should aim at those undesirable persons who indulge in wanton vilification or attack upon the religion of any particular class or upon the founders and prophets of a religion, we must also secure this very important and fundamental principle that those who are engaged in historical works, those who are engaged in bona fide and honest criticism of a religion, shall be protected.”–Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah on the passage of 295-A of the Indian Penal Code (also Pakistan Penal Code)

There is a common tendency – common between Islamists and self-hating Pakistanis alike – to tarnish Jinnah’s memory by saying that because Jinnah was lawyer in appeal (for a fee and purely in a professional capacity) for Ilam Din, who was accused and later convicted of murdering Raj Pal for publishing a scurrilous publication on the life of the Holy Prophet (pbuh), he somehow would have endorsed the blasphemy law as it exists today.

I have addressed the canard of Jinnah’s representation of Ilam Din here in detail. There is no doubt that in retrospect, this was a mistake on part of Mr Jinnah (and The Pratap newspaper was right in criticising Jinnah then and there) but it is important to note that unlike all major Muslims leaders from all sides of the spectrum, Jinnah did not use this for political capital at any point.

I challenge anyone who takes up this point to produce a single public statement of Mr Jinnah defending Ilam Din or presenting it as a great service he did to Muslims. If you can’t, then continuously arguing either that Jinnah endorsed the blasphemy law or that he did it for a venal motive at a time when he was in a very strict sense an Indian nationalist, is useless.

There is a tendency on part of revisionist Islamists as well as his detractors to approach Jinnah’s life piecemeal. For example, everyone from all sides of the spectrum claims that Jinnah disowned his daughter for marrying a Parsi (not true in the least – she was not disowned) but without exception all of them forget that Jinnah, till the end of his life, continued to support the bill to allow inter-marriage between people of different communities without mandatory renunciation of parent faith.

Jinnah said:

“May I ask the honourable member, is this the first time in the history of the legislation of this country that this council has been called upon to override the Musalman Law or modify it to suit the times? This council has overridden and modified the Musalman Law in many respects… This is an entirely optional character of legislation and it is not at all compulsory that every Muhammadan shall marry a non-Muhammadan or that every Hindu shall marry a non-Hindu. Therefore, if there is fairly a large class of enlightened, educated, advanced Indians, be they Hindus, Muhammadans or Parsis, and if they wish to adopt a system of marriage, which is more in accord with the modern civilisation and ideas of modern times, more in accord with modern sentiments, why should that class be denied justice?”

As I pointed out in one of my articles, Jinnah went on to state a few opinions in the speech that may well have attracted the epithet of ‘blasphemer’ in today’s Pakistan. Salman Taseer was assassinated for much less than what Jinnah said. Throughout the Pakistan Movement, Congress’s favourite cleric – Maulana Madni – repeatedly attacked Jinnah for having supported this bill.

But coming to the blasphemy laws, Jinnah’s career as a legislator is testament to his forward and progressive views on the issue of freedom of speech. In the quote at the first instance, Jinnah was the only Muslim member who warned against the misuse of such laws as 295-A.

If one can fault Jinnah, it can be that as a barrister, he took a case not knowing that in Pakistan of 2015 people will see his professional defence of a murderer as an endorsement for the murder or for 295-C.

It is clear, however, that Jinnah would never endorse a law but would rather fight against a law that would seek to stifle public debate and honest bona fide criticisms of religion – whatever religion that may be. Jinnah’s role as a barrister in appeal cannot supersede his role as a legislator where he stated clearly and frankly his personal and political views on the matter, which was to repeat:

“We must also secure this very important and fundamental principle that those who are engaged in historical works, those who are engaged in bona fide and honest criticism of a religion, shall be protected”.

My advice to Islamists who bring up Jinnah while defending the blasphemy law and those who criticise him, is to read the facts for what they are instead of shooting off like a bunch of befuddled fools who have neither the ability nor the acumen to understand the distinction between the profession of law and the vocation of a politician/legislator. It is obviously too esoteric a distinction – however important – for smaller minds to make.

[poll id="380"]

The post originally appeared here.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ