“Baji, do you know why our men don’t want Imran Khan to come into power? It is because they are scared that women in the villages will gain strength if he becomes our prime minister. Already, he supports women standing up for their rights. The jalsas are a proof of this. But we will make sure he wins. We are by his side.”

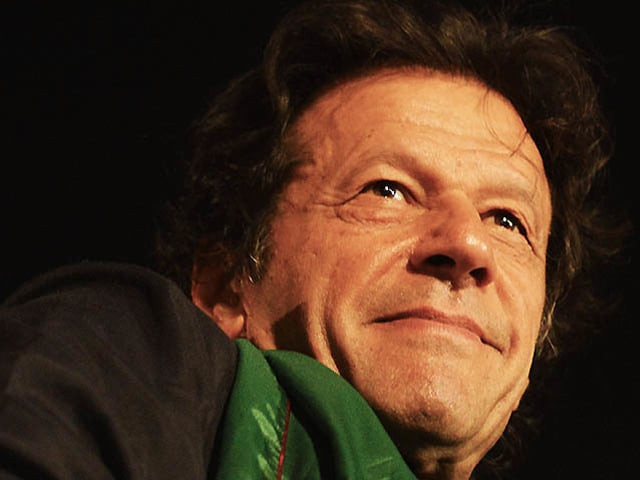

This was the morning after Imran gave an inspiring and honest talk from his container as PTI celebrated “Justice for Women Day”. I had heard that Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) would be celebrating this day a few weeks earlier from a friend who is active in PTI, and a close aid of Imran. I had asked her if the date, November 25th, had been chosen to coincide with the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

“Really? It’s the same day? I’m not sure. You know how PTI works. We do what feels right, for the rights of the downtrodden. Doesn’t matter if it’s a special day or not.”

My default setting had taken over, and I had asked her if they had invited any known human rights’ activists for the occasion. She smiled and said,

“They don’t like us very much you know.”

As a human rights activist and a journalist who reports passionately on human rights and has friends from the field, I also support PTI’s stances on most things, if not all, and look up to Imran as a real hope for Pakistan, as a sincere leader, a philanthropist and humanist. The two things seem like opposites, which is why for a while I procrastinated writing this blog because it would mean choosing sides. Only, the traction is interesting, because I am clearly on both sides.

As for Imran, I see him as a proponent of human rights. He may not be the stereotypical human rights activist of Pakistan, and may not fit the niche group. But he stands up for the underdog, always. And that is what human rights work essentially is – to stand up for the marginalised and vulnerable communities – women, children, minorities, people in conflict zones, people suffering from injustice, people who don’t have money to pay hospital bills and send their children to good schools. The man stands up for social equality. His humanitarian work is a reflection of his belief in equal rights for all.

What then is the problem? Why won’t the human rights activists accept him and his work? They love Shaukat Khanum Hospital and Namal College, but certain things he said and did seem to have ruffled just the right (or left) feathers.

Being the advocate of both the devil and the angel (and I do not know who is who in this case), there are certain things at play here. For starters, while people like Edhi and Chiipa, and organisations like Alamgir Welfare Trust and even Jamaat-e-Islami’s (JI) social welfare wing’s efforts are lauded, they are seen as ‘humanitarian’ efforts. Human rights and their advocacy are seen as a different animal in Pakistani society, and over its history of more than six decades, a certain niche group of people have started being associated with this in the country. They are, in fact, seen as the stake holders of human rights. And with the package come certain pre-requisites. You have to be leftist, or left-off-centre, or at least completely secular, and be someone who does not bring religion into any talk of human rights.

I recall at a recent moot about women-friendly legislation where I was a panellist, a suggestion was floated that following the example of Indonesia, local Imams and clergy members be sensitised to women’s rights, and this be made a part of primary education. At this point, a very known and respected human rights activist who has contributed much to the country stood up in rage,

“What has religion got to do with this? Why must we bring God into everything?”

As much as we tried to explain that this could be done for all religious sects and leaders of minority communities could also be brought on board to fight evils like domestic violence, her reaction remained angry, till the organisers promised that the idea would be dropped.

Imran, in comparison, is clearly centrist in his approach. He cites examples from the life of the second righteous Caliph, Hazrat Umar (RA) and is clear that his dream is that “Pakistan should be an Islamic welfare state with equal rights for all”. In October this year, he dared to question the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) regarding where their funding comes from. Imran’s take is that anyone and everyone should be open to being questioned. But the reaction, not surprisingly, was “how dare he”, given the truly amazing work that has come out of HRCP for the people of Pakistan. This came as a retort to the HRCP saying that Imran and his party’s sit-ins are distracting from more important human rights issues. Add to it the very open issues between the Imran Khan camp and the Asma Jahangir camp. There is a history here, which I wish to leave aside. But the fact remains that this situation has added yet another dimension to the polarisation in Pakistani society.

The human rights camp remains unforgiving of Imran’s earlier stances on many issues, for example his earlier take on certain women-friendly legislations, or his openness to the idea of talking with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). His present softer stances are seemingly not enough for them to give him a chance and work hand in hand for a better future for Pakistanis.

This leaves people like me in a predicament, people who see sincerity on both sides; people who feel bridges should be built between both sides.

It is ironic that I am writing this a day after my paper published a report by human rights group Reprieve, stating that the CIA killed a whopping 221 people, including 103 children, in Pakistan in the hunt for just four men, and that 24 men were reported killed or targeted multiple times; missed strikes on these men killed 874 other people, and account for the 35% of all confirmed civilian casualties in Pakistani drone strikes. The humanist in me cannot write-off Imran as a humanitarian as well as a human rights activist, knowing that he took the strongest stance against “collateral damage” in drone attacks, which is a gross violation of human rights, and his work in the field of public health, education and his stand against injustice.

We live in times where things are neither simplistic nor black and white. If Pakistan has any hopes of uplifting the downtrodden in our society, the thing to do is to appreciate whatever good is being done by any one, whether from the left, the right or the centre. Imran has and is doing a lot of good for our people and stands up for their rights. He may not be your typical human rights activist, but he is one all right. One of the best.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ