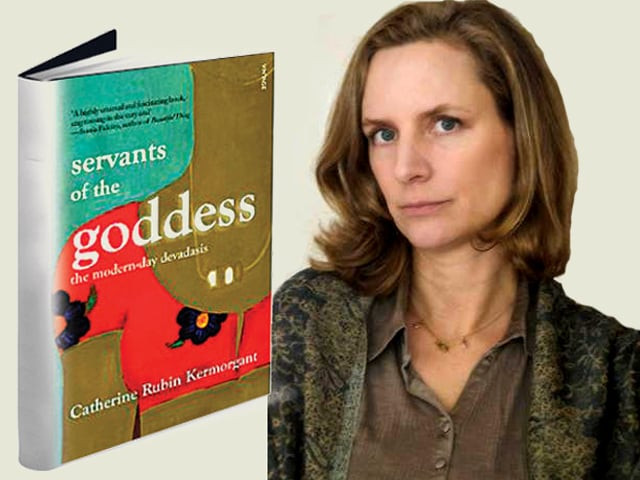

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.

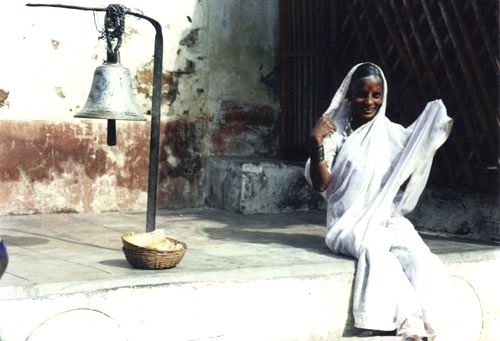

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.Imagine being dedicated to a temple at the age of six years and wearing a beaded necklace for the rest of your life. Imagine being a mother of two at the age of 15 (or even less). Imagine never being able to marry because:

“You’re attached to the temple for the holy duty you have been assigned.”

Imagine a life of a forced sex worker, of poverty, of never being able to provide for your kids. And imagine all this while being (or called) an ‘untouchable’.

Servants of the Goddess is Catherine Rubin Kermorgant’s debut book which came out in February, 2014. It describes the lives and sufferings of modern devadasis in a small village in India.

Kermorgant, in her book ‘Servants of the Goddess’ states that, after conducting research, in Paris, about the life of a devadasis, she set out for a small village called Kalyana in India in order to learn more about truths and myths regarding the devadasi system in India. She may also make a documentary sponsored by BBC on her findings. Along with her interpreter, Vani, Catherine learns about the heart-wrenching tales of devadasis; their stories of being dedicated by their families against their will and when they did not even have any knowledge of why they were being ‘beaded’ at a certain age.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.Etymologically, devadasis are courtesans or dancing girls attached to temples. However, the public more or less calls them prostitutes as they are bound by this profession to grant such favours to the visitors of the temple (or anyone else for that matter) in return for money. And hence, it becomes a thread of survival for them. These devadasis are mostly untouchables dedicated to the temple at very young age (mostly before puberty) by their family and live their whole life providing sexual services in the name of religion.

The more Catherine comes closer to devadasis of Kalyana, the more she realises the misery of these women: there’s poverty, kids at a very young age and never being able to marry (they can take a ‘Jhoolva’ husband who may or may not decide to leave them after actually getting married). They also have to earn money to support their whole family, even bearing the responsibility of marrying off their brothers. So it hardly comes as a surprise to Catherine when she learns that devadasis mostly die young, in their fifties at maximum, by either committing suicide or living the latter part of their lives as alcoholics or becoming severely depressed.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.The book is divided into three parts: the first part discloses Catherine’s field research where she develops life-long bonds of friendship and love with the devadasis of Kalyana, reassuring them that she would share their story of oppression and destitution with the world. The second part of the book portrays her journey back to Kalyana along with her film team and the co-director, Dillip, a pretentious high caste Brahman Hindu who is of the opinion that devadasi system is more of an old Indian cultural tradition than exploitation of poor women. He is adamant on emphasising upon the pros of the system, such as financial stability etcetera. She is all set to document the lives of young devadasis in the hope that it might bring a positive change in their lives by being noticed internationally.

Moreover, the second part of the book also pours light on the caste and class differences, where Catherine experiences first-hand the treatment of low caste, untouchables, by the high caste film crew. It is almost astonishing for the author to witness such cruel treatment of one human being by another just because one was born in a less fortunate household than the other.

The last part of the book, I think, is basically why Catherine decided to write a book in the first place. Although the devadasis had been filmed for weeks in their village and made to tell their woeful stories in front of strangers, Dillip was resolute on showing devadasis in the light of nothing but a glamorous culture of Hindu religion.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.

Photo: Catherine Rubin Kermorgant, taken from official website of the author.The way Catherine describes her experiences with class differences, are shocking for her but not so much for either her film crew (the upper caste Hindus) or the devadasis (untouchables) of the village. This only made me realise how we, too, have categorised, either consciously or unconsciously, ourselves into classes on the basis of religion, language and ethnicities, and are consistently persecuting their rights only to make ourselves feel secure.

For our part of the world, where young women are sexually abused frequently or are economically forced to provide sexual services, the book is even more relatable. It reminds you of how, after all those years of partition, we lag behind in empowering women. A certain class of women can rise as high as becoming the premier of a nation, while the poor women continue to be exploited to the core, without a voice.

One has to read the book to know whether Catherine wins her battle of truthfully depicting the lives of devadasis or Dillip succeeds in manipulating the producer in changing the whole story of the film. The author has nevertheless kept the reader fascinated and captivated throughout the book; one laughs when the girls of goddess laugh and cries at the injustices that engulf their daily lives. The book might be based in an Indian village but it hits home every time.

Average rating: 4/5

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ