Instead of relieving me of my worries, the response I received gave way to a wide array of concerns.

“Come on, how many past papers did you guys really do? You can’t expect an A without having done enough past papers!”

I began to notice, with increasing clarity, how much emphasis our teachers put upon the internalisation of what I call the CIE ‘exam formula’.

In Pakistan , where people are quick to condemn the local education system for its corrupt policies and inefficiency, the implications of a CIE 'exam formula' are heavy.

As a 12th grader currently doing my AS level, I feel that the educational arena and its opportunities are perceived in a very dichotomous manner.

Firstly, people engage in the belief that the local examination boards are excessively inefficient. In true reductionist fashion, they cite instances of cheating in examination halls, laughingly point out the typos in a Karachi Board textbook, and express their dismay at the concept of rote learning that local boards are supposedly the sole perpetrator of.

Such notions, in turn, facilitate the glorification and uncritical acceptance of the international examination boards available in Pakistan, of which the most widely-endorsed one is Cambridge International Examinations.

When viewed within the context of South Asia’s colonial history with Britain, such endorsement poses a problematic picture.

I have had the good fortune of taking high school exams through both, SSC and CIE. My experience with the two boards and its candidates has made me come to understand the assumptions made by the two institutions about and towards each other and I have seen how they play into the post-colonial situation of Pakistan.

O/A level candidates have a very poor impression of SSC/HSSC education. They believe it to be superfluous - somehow sub-par and not wholesome enough.

On the other hand, CIE qualifications always merit instant validation from society and assert one's social status. When discussing the shortcomings of the Matriculation system, there is always a sense of gratification shown by O level students.

“Thank God I’m doing O levels! I’d never have been able to ratta-fy (rote learn) so much text!”

Comments like this always make me sceptical because such mentality contributes dangerously to the class divide that exists in educational sectors.

Where does this childish superiority complex end and the hegemonic exploitation of the lower social classes at the hands of the British-affiliated education sector begin?

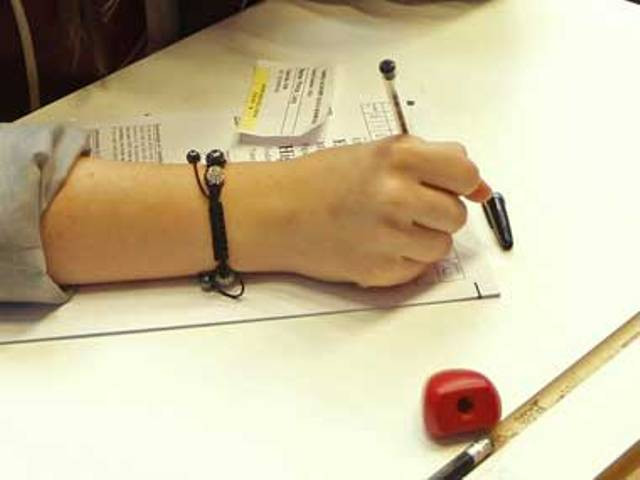

Time and again, especially with the examination date so close, my teachers have emphasised the importance of doing past papers, and frequently impart lessons from 'What CIE Expects from a Candidate.'

To do well in CIE requires monetary resources. Thus, for the upper classes, education through an international education board like CIE is an easy opportunity. The same cannot be said for the lower social classes. They cannot afford the same opportunities, and are yet evaluated on the same standard that society expects of education from an international exam board.

Many would argue that the CIE curriculum is designed specifically in such a way that it keeps in regard the socio-political situation of the countries that it includes. Even so, the insidious effects of a CIE education as a lived experience are immense.

The social divide that I mentioned before is one. Also, through the endorsement of particular texts, CIE has the power to perpetuate Eurocentric colonial images in Pakistan’s society simply by training students to inculcate the CIE “formula” based on which they’ll be graded in their exams. This is not to say that local curriculum and educational boards prescribe the most objective and undistorted texts either, but Pakistan’s geopolitical history with Britain in particular lends problematic undertones to the issue where a Western education board like CIE is concerned.

Such a Eurocentric understanding of Pakistan’s issues, without proper contextual references, has the potential to turn academia into a dangerous space for unsuspecting Pakistani students. So much so that through participation in such an education system, the very purpose of education – empowerment and progress – might even be negated.

Follow Hooria on Twitter @hooriaimran

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ