The second episode was a thought provoking insight into the issue of the language of instruction in Pakistani schools. The episode looked at the emotional trauma and turmoil children face when they are forced to learn or communicate in languages which are completely foreign or alien to them, in our case these being Urdu and English.

It does not only cause confusion in the minds of the students, but may eventually lead to a loss in self-confidence and the ability to express themselves, resulting in a lifelong learning impediment.

The policy suggestion presented in the show was to introduce a tripartite language system at the primary level, whereby children are taught in their mother tongue as the language of instruction (especially if it is a regional or local language) and Urdu and English are introduced as 'languages' which can be built on once they reach their secondary school level.

We know in many developed and developing countries, such as most of Europe, Japan and China, that children learn in their local languages and their education systems are able to compete internationally.

There are successful models of multilingual countries with a federal system similar to Pakistan who have done remarkably well with multilingual education, also known as 'first-language-first' education. The most interesting case being Switzerland which has 26 cantons (regions) and where the language of instruction can be,

"German, French, Italian or Romansh, depending on the language region... All students learn at least two other languages during their compulsory schooling. This is generally one of the other languages spoken in Switzerland and English," according to the EDK, the Swiss national education coordination agency.

On the face of it, the policy sounds great in principle. However, in the Pakistani case, there would be many challenges to the implementation of such a policy.

For one, Pakistan has its own historical legacies to contend with, the first being colonisation. The subcontinent was colonised for nearly a 100 years, during which time local languages were gradually devalued and later learning English was the only option left, if one had to work in the vast civil service or government jobs. This unfortunately is true, even more so, to this day.

The second legacy is the adoption of Urdu as the national language, which ironically wasn't the language of any of the geographical areas which formed the country, but of Muslim League leaders who were migrating from India. It was fair in the sense that it was unfair to everyone local, and gave some advantage to those who had left everything behind.

However, this 'Urdu only' policy led to disastrous consequences to the country's federalism of which the secession of the Bengali-speaking 'East Pakistan' was the worst example. The language riots may not have been the only or defining factor in this, but they were definitely an important one.

One would have hoped we would've learnt our lesson and started to value regional languages. In reality, it provoked the opposite reaction with even more emphasis on national unity and the national language being the language of instruction.

Even if you leave the historical legacies aside, there is the irrational fear of political wrangling and corruption which can take the policy years to be implemented, much longer than the political horizon of any government. Constant changes in policy wreak havoc to an already failing education system.

Another important factor would be the compliance of the booming private education sector in Pakistan. Already the privately educated have an advantage because of their better quality of education and relatively superior grasp of English. A policy also introducing regional languages to the mix for government schools may further disadvantage those from the poorest backgrounds, rather than aiding learning.

How would we ensure that private schools also adhere to the policy?

Also to consider, though this is something we can work on and aim to improve, there is a lack of resources available in regional languages. Very few books are available in Urdu, let alone in regional languages, that deal with technical or scientific topics and a significant investment would have to be made to produce and translate content in these languages. For example, while many people in Khyber-Pakhtunwa may speak Pashto, very few of them know how to read or write in their mother tongue. And, even within a province like Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, there are many Hindko speakers.

So we may be opening up a Pandora's Box!

If we agree that multilingual education is something we want and aspire to, how do we get there?

I would love to hear from others, especially those with an education background, of what can be done in the short- and long-term. And especially lessons that we can learn from other developing countries, particularly our neighbour India who shares our colonial legacy and for whom multilingualism is an even bigger challenge than it is for us.

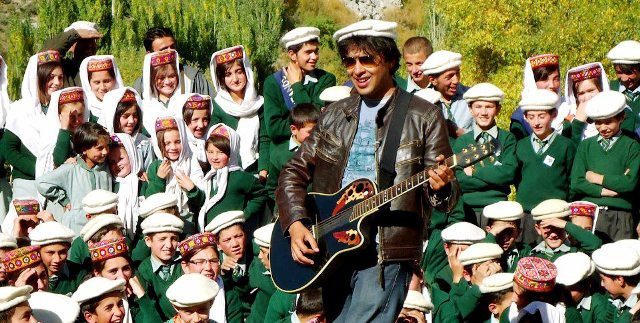

A huge thank you to Zara Sochiye, the campaign team behind Chal Parha, for getting the debate started and for trying to make education an important policy issue for the upcoming election in Pakistan.

I am looking forward to what the next episode has to offer!

Read more by Tamreez here, or follow her on Twitter @tamreezinam

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ